Just two months before the decisive battle of Midway, the Indian Ocean was the scene of Operation C - a face-down between the fleets of Britain and Japan. Their carrier forces came within just 100 miles of a clash that could have changed the course of the war.

“The most dangerous moment of the war, and the one which caused me the greatest alarm, was when the Japanese fleet was heading for Ceylon and the naval base there. The capture of Ceylon, the consequent control of the Indian Ocean, and the possibility at the same time of a German conquest of Egypt would have closed the ring and the future would have been black.”

PRELUDE

By March 1942, Britain was drained. After two and a half years of intense warfare, her flagging forces had been pushed beyond the limit.

Initial excitement that the US had finally been drawn into the war by Pearl Harbor quickly evaporated. The string of military disasters which exploded across South-East Asia following Pearl Harbor soon saw the tribulations of 1939 and 40 pale into insignificance.

With the fall of Singapore on February 15 and the impending collapse of US forces at Bataan, the Royal Navy had to face fighting alone on yet another front - the Indian Ocean.

The rolling tide of Japanese success seemed unstoppable. Germany and Italy were steamrolling their way across Africa.

That the Axis would merge at some point between India and the Middle East appeared almost inevitable. Worst-case estimates projected that the Middle and Near East, the Caucasus, India and all of South East Asia would be under Axis control by September.

All that stood in their way was the British Eastern Fleet.

This was virtually non-existent.

Four days after Singapore capitulated, the Port of Darwin in northern Australia was smashed.

The Admiralty estimated it had just six weeks to assemble a viable defensive force for the strategic Indian Ocean island of Ceylon.

Their calculations proved almost correct.

On March 8, 1942, the First Sea Lord informed Prime Minister Winston Churchill that he regarded Ceylon to be Japan’s next target.

Admiral Pound warned its loss would ‘undermine our whole strategic position in the Middle as well as the Far East'

The fall of this, the fulcrum point of the Indian Ocean’s shipping lanes, would sever trade routes with Australia and New Zealand. As a staging post, it would allow Japan to raid the resources of India and vital oil fields of the Middle East.

Churchill quickly realised that, after the loss of HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse, the fall of Singapore and the disaster at Darwin, this was the most dangerous moment of his political career. Just weeks earlier he'd been forced to face-down a no-confidence vote in Parliament.

If Ceylon fell, there was little doubt it would bring down his battered coalition government.

It would be one defeat too many.

“A Japanese naval victory in April 1942 would have given Japan total control of the Indian Ocean, isolated the Middle East and brought down the Churchill government.”

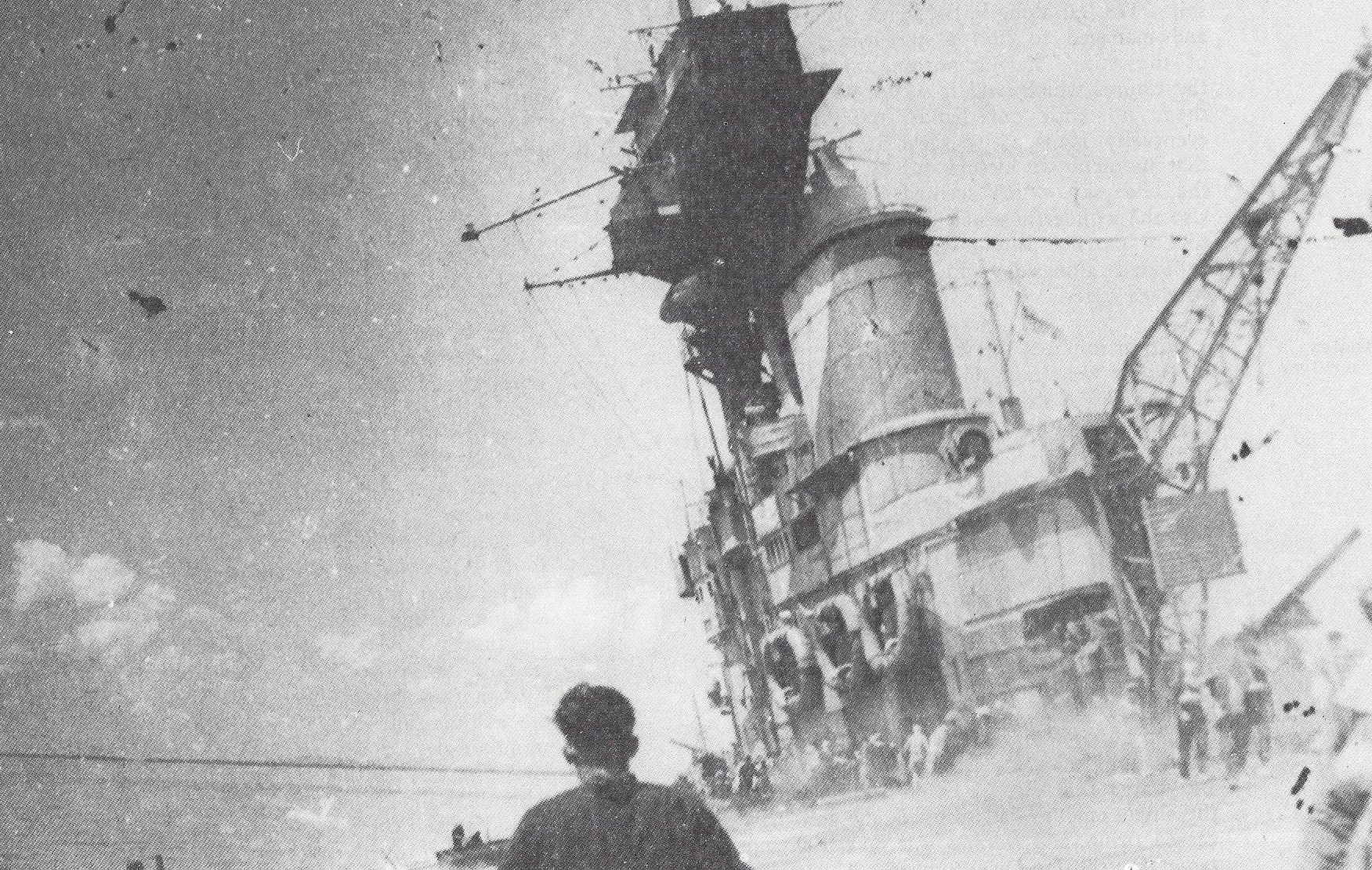

Photograph taken from a Japanese aircraft during the initial high-level bombing attack. Repulse, near the bottom of the view, has just been hit by one bomb and near-missed by several more. Prince of Wales is near the top of the image, generating a considerable amount of smoke. Japanese writing in the lower right states that the photograph was reproduced by authorization of the Navy Ministry.

STRATEGIC OVERVIEW

“Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville. An unusual admiral this one, popular with aircrews as well as the ship’s company because from all accounts he took a keen interest in all aspects of naval aviation. Perhaps having a nephew who was an aircrew observer prompted his interest. For example, Somerville would spend time on the flight deck to study how it was working rather than remaining perched on his high stool in the compass platform.. ”

The need for a strong British fleet in the Indian Ocean became urgently clear in the dawning days of 1942.

With the fall of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands along with northern Sumatra, the narrow sea lanes to Singapore and Malaysia were severed. It was obvious an attack on Ceylon was imminent.

The strategic Indian Ocean island of Madagascar was also under threat. The Vichy government had already handed control of French Indo-China to the Japanese, allowing them to use its airbases against Singapore. If the same was to happen to Vichy-controlled Madagascar, the Cape of Good Hope could be closed.

But finding enough ships to do something about this was a cause for desperation.

Admiral Sir James Somerville was urgently appointed as Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Fleet.

The core of his command was just the old, unmodernised battleships HMS Ramillies and Royal Sovereign.

Even as he prepared to move his flag to Colombo, Somerville was shocked at the scenario unfolding before him: 'How is it considered that two R-class under fighter cover can repel a landing? It seems to me that unless we have a balanced force we may get a repetition of Prince of Wales and Repulse'.

Despite this realisation, Britain was simply not in a position to meet the Japanese threat head on.

But Churchill knew his political neck was on the line.

So the hero of Matapan and Calabria, HMS Warspite, was routed to Colombo via Australia after repairs in the United States. Refugees from the fall of Malaya, the Dutch Heemskerck and Isaac Sweers, along with HMAS Vampire, were redeployed along with the cruisers HMS Enterprise, Dragon and Caledon. The heavy cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire were already there, though the latter was undergoing a refit. The light carrier Hermes had been busily engaged in anti-submarine escort duties, while HMS Indomitable had been rushing Hurricanes to the defence of Malaysia. The remaining R-class battleships, HMS Resolution and Revenge, joined their sisters in the Maldives, along with the redeployed Indomitable and eight destroyers. Rounding up the force was six submarines.

Despite the apparent might of this force, Admiral Somerville quickly grasped the impossibility of his position.

He told the Admiralty that had no chance against the main strength of the Japanese navy. Even if an invasion was supported by only a moderate force, 'the best counter is to keep an Eastern Fleet in being, and to avoid losses by attrition… if the Japanese capture Ceylon and destroy the greater part of the Eastern Fleet, then ... the situation becomes really desperate'

Admiral Somerville himself would board the freshly repaired armoured carrier HMS Formidable as it made its way eastward. En-route to Colombo, he had the air group practice what he regarded to be a vital skill: Night torpedo attack.

Somerville knew he faced the very real prospect of the war's first carrier-versus-carrier clash.

Minute from Secretary of Chiefs of Staff Committee to Prime Minister

[PREM 3/ 142/ 1] 24 February 1942

Diversion of HMS Indomitable’s Hurricanes from Java to Ceylon

NOTE ON CEYLON.

Importance of Ceylon.

1. Ceylon occupies key strategic position and essential as secure base for control of our sea communications in Indian Ocean, including Middle East reinforcement route and routes to Australia, India and Burma.

2. Supplies to China necessary for continuation of Chinese war effort depend on security in Indian Ocean.

3. Should Ceylon fall into enemy hands our whole military (when used in its widest sense) position in the Indian Ocean would be jeopardised and we could no longer ensure the above lines of communication.

4. Loss of N.E.I. and tanker shortage makes regular flow of oil supplies from Abadan vital to successful continuation of war and enemy naval forces based on Ceylon would be a threat to these supplies.

5. Trincomalee and Colombo both required as bases for units of Eastern Fleet. Neither of sufficient capacity alone. Colombo also essential [as] convoy assembly port. These bases must be secure if Fleet is to have freedom of action to cover important routes.

6. The following is the present position regarding the defence of Ceylon. Air.

7. There are no formed squadrons based on Ceylon at present, but there are a few Swordfish and Albacore aircraft in the Island. 2 squadrons of Fulmar fighters arrive shortly and by the beginning of March a considerable force of Hurricanes with their personnel, on passage through the Indian Ocean, will be in the vicinity of Ceylon and can be landed there if the situation demands. Anti-Aircraft Defence

8. By 28th February there will be 52 Heavy and 64 Light A.A. guns in the Island. More are on the way. Army.

9. The present position is weak and consists of-

Headquarters 24th Indian Division

2 Brigades Indian Infantry

1 Battery Field Artillery

1 Anti-Tank Battery and equivalent of

1 Brigade local troops

10. Reinforcements at present on way to Ceylon consist of 1 Brigade Group 70th British Division due to arrive mid-March and 1 Armoured Car Battalion (Indian) due in April. Further reinforcements still under consideration.

TACTICAL SCENARIO

“The trouble is, the fleet I now have is much bigger than anything anyone has had to handle before or during this war. Everyone is naturally very rusty about doing their “fleet stuff” – most ships have hardly been in company with another ship during the war. On top of all that, most of my staff are pretty green, so I have to supervise almost everything myself. It will improve as time goes on but it certainly is the devil of a job at present.”

The entire corpus of thinking for naval warfare had just been stood on its head. The destruction of HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse had finally rammed home the vulnerability of capital ships in the face of air opposition.

No time had passed to figure out how to counter it, beyond the realisation that fighter cover was now absolutely essential in any naval action.

But it was already obvious carriers reigned supreme in the open waters of the Pacific.

Admiral Somerville was in an almost impossible position. Not since the opening days of the war had two RN fleet carriers operated in concert. Even a force of four battleships had been a rare luxury.

As a result, fleet formation and manoeuvre discipline had inevitably waned.

Then, barely after he stepped through the door of his headquarters in Colombo on March 24 to assess his new command, ominous intelligence reports began to roll in.

Japan was sending a strike force into the Indian Ocean.

He immediately called a conference of his available captains.

Intelligence stated a Japanese force of two or more carriers, battleships of the Kongo class, several eight-inch cruisers, two six-inch cruisers and accompanying destroyers was believed to already at sea.

If correct, this was a powerful - yet opposable - force.

Expected time of arrival: March 31. As a full moon was forecast for April 1, Somerville and his advisers were convinced the attack would be launched before dawn that day.

Somerville was in a bind: Admiralty discussions before his arrival in Ceylon had indicated a degree of aggressiveness. Now the tone of their communiques was much more defensive.

He felt he had just one choice: To concentrate his fleet outside the range of Japanese reconnaissance during daylight, and close at night. The British could use their radar-equipped Albacores to slow the Japanese fleet enough for their battleships to engage in the dark.

To achieve this, Somerville had an ace up his sleeve.

Addu Atoll.

Click on the image for an enlarged view.

This was a hastily assembled secret Admiralty base on the southernmost tip of the Maldive Islands, 600 miles south-west of Ceylon. It was intended to allow a fleet to anchor and refuel away from the eyes of roving reconnaissance planes.

While it lacked anti-submarine and anti-aircraft defences, It nevertheless gave the Eastern Fleet a chance to pick and choose the timing of a fight.

Mistakenly, he believed the Japanese – like the Italians and the US – had no skill at naval night fighting, either in the air or on the surface. But Somerville knew the precarious position he was in.

He signalled the Admiralty that his strategy would be “to keep the Eastern Fleet in being and avoid losses by attrition”. He would do this “by keeping the fleet at sea as much as possible; to avoid it being caught in harbour; to avoid a daylight action whilst seeking to deliver night torpedo attacks; and not to undertake operations that do not give reasonable prospects of success.”

The Japanese, he knew, held the high ground.

Just weeks earlier, the combined US-British-Dutch-Australian forces had been destroyed in and around Java.

Churchill was convinced an invasion force was on its way.

Germany was agitating for a fully-fledged invasion of Ceylon. Japan, however, had other priorities.

British intelligence was aware of Hitler’s ambitions. But not of Japan’s reticence.

For Japan, it was a matter of neutralising one last remaining threat: The British Eastern Fleet.

Admiral Kondo had, by the middle of March, ordered plans for a two-pronged advance into the Indian Ocean to be drawn up. His objective was to bring the Eastern Fleet to battle, and to destroy it. To achieve this, Admiral Nagumo’s elite, and now veteran, carrier strike force was available.

Everything hinged on the success – or otherwise – of reconnaissance. For both navies.

ORDER OF BATTLE

“... at this rate we shall have hardly any aircraft left by the time we arrive; but it’s no good having aircraft if the chaps can’t fly them properly. My old battle boats are in various states of disrepair and there is not a ship at present that approaches what I should call a proper standard of fighting efficiency. This ship (Formidable) evidently wants a proper training programme, which I hope to give her as soon as the weather becomes favourable.”

At first glance, the freshly-formed British Eastern Fleet appeared powerful. In fact, it was one of the largest ever assembled by the RN during the war years.

But scratch the surface, and the problems were obvious.

Few of his ships were modern. Most were slow. None were designed for operations under the stifling Eastern sun, nor the open expanse of the Indian Ocean.

The two large and modern aircraft carriers represented a significant chunk of the surviving carrier force. The smaller Hermes was still useful as an escort.

But Somerville regarded his pilots to be an ill-matched jumbled of veterans and untried - untrained - recruits. And the fleet carriers still operated aircraft barely capable to countering Italy and Germany’s long-range land-based fighters and bombers. Certainly not Japan’s unexpectedly capable carrier-based Zeroes, Vals and Graces.

The handful of Martlet and Sea Hurricanes aboard his two fleet carriers were simply not enough to make a difference against the raw numbers carried by the Japanese – yet alone the well drilled and highly experienced pilots of Nagumo’s fleet.

Somerville's modernised flagship Warspite would combine her eight formidable 15 inch guns with those of the four heavily armoured R-class battleships. But the Rs, with their outmoded design, were barely capable of 18 knots. Several of his antique 6-inch gun cruisers had not had their old armaments upgraded. The 8-inch County class cruisers were poorly protected for their size. And the destroyer force was an eclectic mix of compromises.

Admiral Somerville also was under no illusions as to the strength of the force under his command.

At least, by day.

Lt Cdr N. C. Manley-Cooper, aboard Ark Royal, in Ray Sturtivant's British Naval Aviation

In early May 1941 air-to-surface vessel radar (ASV) arrived on 820 Squadron. Nobody thought this new invention would really work but it was put into my aircraft and thus I became the first ASV operator in the Mediterranean Fleet. The equipment was quite bulky, taking up most of the cockpit space underneath and in between the pilot and observer.

On May 17 we took up Vice-Admiral Somerville for an ASV demonstration: he was quite interested in wireless and wanted to see this new development for himself. My pilot on this occasion was Sub-Lt Mike Lithgow, later to become well known as a test pilot. We first had a little practice, and I was able to bring the aircraft out of the clouds right over the ship. The Admiral was very impressed by this, and asked to see for himself how it was done. We put him into my cockpit and showed him what to operate whilst I leaned over from the TAG's cockpit. Unfortunately he put his hand on the wrong know, in which there was a lot of electric current, and he promptly shot up to the extent of the G-string holding him in! After he had recovered from this we flew in cloud close to the Fleet, and I said 'Sir, there is your flagship'. We came out of the cloud and there was Renown. 'Dead easy, isn't it?' he said - having just suffered a very nasty electric shock!

The two-seat Fulmar, while outclassed by the Zero, could however be operated at night. Its performance was also superior to that of the Hurricane when it came to low-level intercepts. And the torpedo-bomber Albacores were fitted with the latest – and highly secret – airborne surface-search radars.

Exactly how many Albacores - and on which carrier - were equipped with the game-changing device is unclear, but numbers appear to have been adequate. Air Observer Gordon Wallace, in his book Carrier Observer, was flying in Albacores aboard HMS Indomitable at this time. He says the ASV (Airborne Surface Vessel radar) was fitted only to HMS Formidable's Albacores. But other accounts state the opposite. Formidable also reportedly retained a single Swordfish among her strike wing - because it had a precious ASV set.

Indomitable's air group was somewhat under strength, and those she did have aboard had missed out on vital training while the ship was employed ferrying RAF Hurricanes to Malaya. HMS Formidable had only just returned from extensive repairs in the United States. Her Martlet pilots had completed a suitable working up period, but her Albacore squadrons were barely capable of carrier operations.

A round-table conference between Admiral Somerville and his captains strove to determine the best composition of a balanced force.

It was agreed the faster light cruisers Emerald and Enterprise could join with the heavy cruisers and Warspite to present a formidable threat – under the confusion of darkness. The remainder would have to do what it could from a supporting position to the west.

But all agreed any defeat would leave the critical convoy routs of the Indian Ocean exposed, and open the way for an invasion of India itself.

Then an order arrived from the First Sea Lord: Somerville was not to allow his fleet to become engaged with anything other than an obviously inferior force.

Somerville’s instructions were clear: He must adopt a purely defensive stance.

But he could choose one capable of being quickly turned to the offensive if an opportunity presented itself.

Admiral Somerville had been handed this opportunity by the code-breakers who had sifted from the torrent of Japanese radio traffic news of an impending strike on April 1 against Colombo. He received this vitally important intelligence on March 28.

With careful timing, the Eastern Fleet could strike when the Japanese were most vulnerable: At night, when the carriers were preparing to launch a ground attack.

But the intelligence report underestimated the Japanese force composition. Nor did Somerville hear that Vice-Admiral Nagumo had postponed his departure date until March 26: The Japanese commander had wanted to wait until the intentions of a US carrier force spotted near Wake Island on March 10 had become clear.

The resulting delay of the strike on Ceylon until April 4 seemed insignificant in Nagumo's mind.

It would, however, almost prove to be Admiral Somerville’s undoing.

ROYAL NAVY

“There had been intelligence the Japanese were planning some sort of raid or foray into the Indian Ocean and we felt we had very little time to get ourselves in a fit state to meet them. The Warspite was at Bombay, the four R Class battleships were coming around the Cape to join, and the aircraft carriers, which had been occupied ferrying aircraft into Singapore for defence, had no recent combat action to ready them to defend the fleet. About a week after I arrived in Bombay the Warspite sailed and rendezvoused with this fleet. On paper it was most impressive. But in fact, when we finally all met up at sea, Admiral Somerville had not even had an opportunity to meet his captains or more junior admirals before undertaking the fleet’s first operation.”

* Lamb may have meant Colombo when he states Bombay: Warspite did not venture to Bombay until after Operation C

FORCE A (Fast Group):

Aircraft Carriers:

Indomitable (Rear-Admiral D. W. Boyd):

- 880 Squadron (9x Sea Hurricane Ib)

- 800 Squadron (12x Fulmar II)

- 827 Squadron (12x Albacore)

- 831 Squadron (12x Albacore)

Formidable:

- 888 Squadron (12x Martlet II)

- 820 Squadron (12x Albacore I)

- 818 Squadron (9x Albacore I, 1x Swordfish I)

Battleships: HMS Warspite (Flagship, Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville)

Heavy Cruisers: Cornwall, Dorsetshire

Cruisers: Emerald, Enterprise

Destroyers: HMS Paladin, Panther, Hotspur, Foxhound, HMAS Napier, HMAS Nestor

Submarines: Truant, Trusty, O-19, K-XI, K-XIV and K-XV.

* David Brown, in his book Carrier Fighters, states that - out of a paper strength of 37 fighters in total - Indomitable and Formidable only had 21 available and/or serviceable: Six Martlet IIs, eight Fulmars and 11 Sea Hurricanes. (He may have the figures swapped for Fulmars (11) and Sea Hurricanes (8) based on the official order of battle.)

FORCE B (Slow Group)

Aircraft Carrier:

Hermes

- 814 Squadron (12x Swordfish I)

Battleships: Resolution (Vice-Admiral Willis), Ramilles, Royal Sovereign, Revenge

Cruisers: Caledon, Dragon, Jacob Van Heemskerck

Destroyers: Griffin, Arrow, Decoy, Fortune, Scout, HMAS Norman, HMAS Vampire, Isaac Sweers

CEYLON

The situation on the ground was little better. Though not as desperate as it could have been.

Until February, the island's sole air defenders had been two naval squadrons of Fulmar IIs, fresh from fighting in North Africa. 839 Squadron RAF was operating Seals, Vildebeest and some Fulmar Is and IIs borrowed from the navy. Stocks of Hurricane Is were trickling in.

But Ceylon’s meagre air defence was soon supplemented by some 22 Hurricane IBs, veterans of the North African campaign. A fresh force of Blenheim bombers, just arrived from action in Greece, Crete and the Middle East, was shuffled to a hastily constructed auxiliary airfield near Colombo.

It was obviously inadequate.

The newly arrived pilots and maintenance crews were struggling to adapt to the conditions: Just one example of their challenges included a spontaneous fire among incendiary ammunition which resulted in all tracer being removed from among ammunition belts.

Initially, the Catalinas were not ready. Initially, only one aircraft of 240 Squadron was operational after the long flight to Ceylon. The six long-ranged flying boats, with one additional aircraft undergoing maintenance, could not sustain more than three in the air at any given time.

A second squadron of Catalina’s, however, would make a timely arrival on April 2. The Canadian 413 Squadron, under Squadron Leader L.J. Birchall, had flown from the Shetland Islands. But these valuable aircraft would enable the RAF to maintain the necessary patrol pattern to cover a radius between 110 degrees to 154 degrees out to a range of 420 miles.

On the island, however, radar coverage was limited. Only one unit, 524 AMES, had been established in the past few weeks.

ROYAL AIR FORCE Order of Battle

Command: Air Vice-Marshall d’Albiac, Air Commanding Officer of No. 222 Group.

Colombo

This was a small but generally crowded commercial port. Four coastal batteries had been established to defend its approaches. Among its dock facilities were a number of naval facilities, but its character was chiefly civilian. Colombo's air defences included 3 x 12-pounders, 23 x 40-mm, 4 x 3-inch, and about 19 x 3.7-inch guns

Ratmalana: This was a former civilian airfield that had been extended to operate heavy RAF aircraft.

- 30 Squadron: 21x Hurricane IIb

- 803 Squadron: 12x Fulmar II

- 806 Squadron: 12x Fulmar II

Static defences: 12 x 40-mm and 4 x 3.7-inch

Racecourse: This was one of several auxiliary airfields established across the island. With only rudimentary services, its only advantage lay in it not being known to the Japanese.

- 258 Squadron: 10x Hurricane IIB, 7x Hurricane I. This was a re-formed Dominion staffed squadron that had previously been fighting in Malaya with outclassed Buffraloes.

- 11 Squadron: 14 Blenheim IV (11 operational)

Koggala: This was a land-locked lagoon on the southwest coast, near Galle. Its sheltered harbor and remoteness made it an ideal base for seaplanes. It was only just being established, and a ragged assembly of squadrons was in the process of arriving.

222 Group:

- 202 Squadron: 1x Catalina

- 205 Squadron: 1x Catalina

- 240 Squadron: 3x Catalina

- 413 Squadron: RCAF: 3x Catalina.

Trincomalee

One of the finest natural harbors in the world, it was specifically used as the Royal Navy’s East Indies Station. Apart from the dock, maintenance and storage facilities, there was little there. The harbor was guarded by five coastal batteries.

China Bay: This was a wide, grass airfield with the sea at either end. Built to established pre-war RAF principles and standards, it was the best facility in the region.

- 261 Squadron: 16x Hurricane IIb. Previously assigned to defend Malta, this squadron took station here after flying off from Indomitable.

- 273 Squadron: 16x Fulmar I&II, This hastily assembled general reconnaissance squadron under RAF command was actually manned by FAA and Marine pilots.

- 888 Squadron FAA: 3x Martlets (unserviceable due to lack of .50 cal ammunition). This was a training detachment from HMS Formidable for new pilots.

- 788 Squadron: 6x Swordfish I. This unit was a hasty assembled unit of reserve RN aircraft and reinforcements shipped out from the UK.

- 814 Squadron*: 10 Swordfish I. This was HMS Hermes' anti-submarine squadron, detached to China Bay part way through the campaign. A further two were under repair aboard the carrier.

Kokkilai: 15 miles south of Trincomalee, was another of the urgently prepared auxiliary airstrips.

- 261 Squadron (flight) was dispersed here from here from April 5.

Malay Cove: Near China Bay airfield, this was a sheltered beach suitable for amphibian aircraft.

- 321 Squadron (RNAF): 4x Catalina

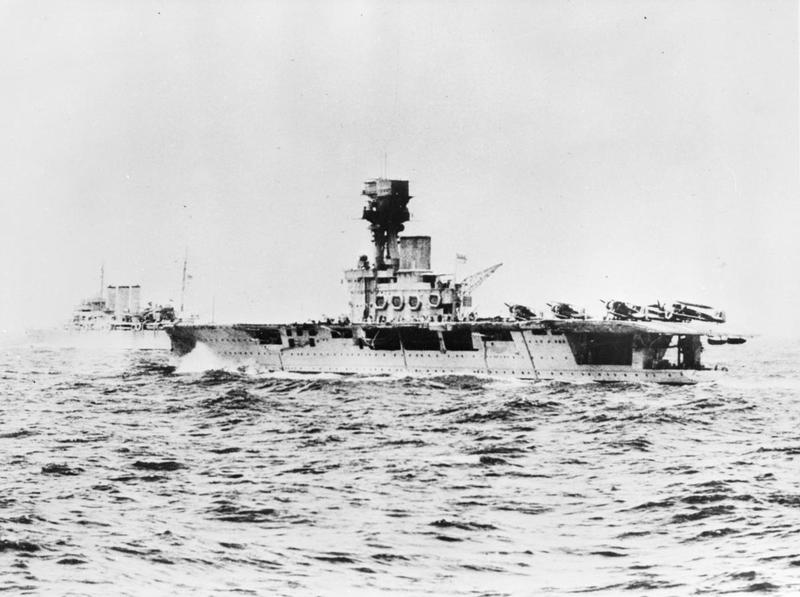

The carriers and battleships of the Japanese Indian Ocean strike force departing Starling Bay, marked as being taken on March 30. A translation of the original caption reads: March, 1942: the task force proceeding across the Indian Ocean: the view, from behind an anti-aircraft gun, front port side of the Zuikaku, shows the battle group in a single column, veering to port directly in front of he Zuikaku, with the carrier Akagi in the lead, followed by carriers Hiryu and Soryu, then battleships Hiei, Kirishima, Haruna and Kongo. The Shokaku is probably cruising to the rear of the Zuikaku

IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY: OPERATION C

The initial Japanese plan was for its First Carrier Fleet to leave the port of Kendari in the Celebes, Indonesia, on March 21. This would allow an attack on Ceylon on April 1.

With Vice-Admiral Nagumo were five of the six carriers that had struck Pearl Harbor: Kaga had returned to Japan for repairs after striking a reef on March 15.

Indomitable was not the only carrier to suffer such an indignity, it would seem.

A second force, consisting mainly of cruisers escorted by the light carrier Ryujo, was to enter the Bay of Bengal to strike shipping and coastal facilities there.

Inexplicably, the Japanese forces were to be split in a four-pronged attack. This went counter to all established Japanese naval doctrine.

It was a tactical blunder that would later be repeated – fatally – at Midway.

Nevertheless, the Japanese expectation was for complete surprise - just like at Pearl Harbor and Darwin.

Port Blair

Seized without opposition earlier in May, the Andaman Islands were to provide an ideal staging post for Japan’s naval and air forces into the Indian Ocean.

To that end a detachment of seven H6K long-ranged flying boats out of an eventual 15-18 were deployed to Port Blair on March 24.

Second Southern Expeditionary Fleet (Vice-Admiral Nagumo

Carrier Division 1

Akagi (Flagship Vice-Admiral Nagumo, Captain Kiichi Hasegawa): 27x A6M2, 18x D3A1, 27x B5N2

* Some sources argue that losses due to combat (40 aircraft), deck landing and mechanical attrition since Pearl Harbor, the Japanese carrier force had standardised their squadrons at 18 operational aircraft each to allow for spares. Therefore Akagi was at this time only operating 18 fighters, 18 dive-bombers and 18 torpedo-bombers (for a total of 54)

Carrier Division 2

Hiryu (Flagship Rear-Adm. Tamon Yamaguchi , Captain Kaku): 21x A6M, 21x D3A, 21x B5N

* Alternate figure given is 18 fighters, 18 dive-bombers and 18 torpedo-bombers (for a total of 54)

Soryu (Captain Ryusaku Yanagimoto): 21x A6M, 21x D3A, 21x B5N

* Alternate figure given is 18 fighters, 18 dive-bombers and 18 torpedo-bombers (for a total of 54)

Carrier Division 5 (Rear-Adm. Hara)

Zuikaku (Captain Ichibei Yokokawa): 18x A6M, 27x D3A, 27x B5N2

* Alternate figure given is 18 fighters, 19 dive-bombers and 19 torpedo-bombers (for a total of 56)

Shokaku (Captain Takatsugu Jojima): 18x A6M, 27x D3A, 27x B5N2

* Alternate figure given is 18 fighters, 19 dive-bombers and 19 torpedo-bombers (for a total of 56)

3rd Battleship Squadron

Kongo (Flagship Rear-Adm. Gunichi Mikawa), Haruna, Hiei, Kirishima

8th Cruiser Squadron

Tone (Flagship Rear-Adm. Hiroki Abe ), Chikuma

Destroyer Squadron 1, 1st Fleet

Light cruiser: Abukuma (Rear-Adm. Sentaro Omori)

Destroyer division 17

Urakaze, Tanikaze, Isokaze, Hamakaze

Destroyer division 18, Destroyer Squadron 2, 2nd Fleet

Kasumi, Arare, Kagero, Shiranuhi, Akigumo

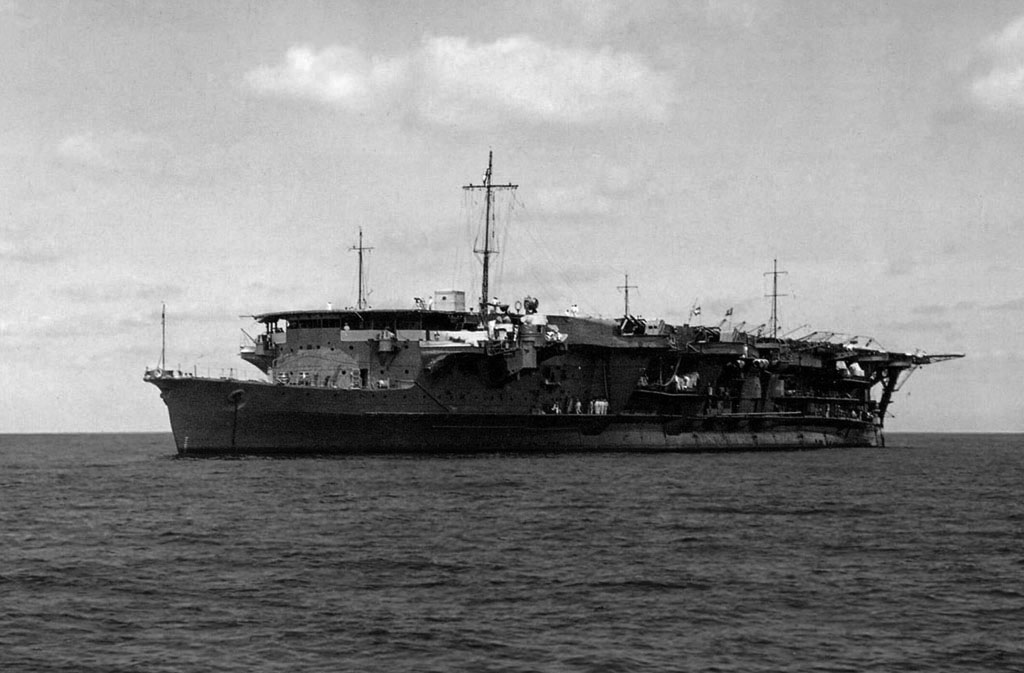

The light carrier Ryujo.

Second Expeditionary Fleet (Vice-Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa)

This force, based in Mergui, Burma, was waiting for Nagumo to arrive before raiding shipping in the Bay of Bengal and bombard installations along India’s east coast. This force was divided into three separate units, not along division lines.

Heavy Cruiser: Chokai (Flagship Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa)

7th Cruiser Squadron

Kumano (Flagship Rear-Adm. Takeo Kurita), Mikuma, Mogami, Suzuya

Cardiv 4

Ryujo (Flagship Rear-Adm. Kakujo Kakuta): 12 A5M4 and 15 B5N1/2

Destroyer Squadron 3, 1st Fleet

Light Cruiser: Yura

Destroyer Division 11

Fubuki, Shirayuki, Hatsuyki, Murakumo

Destroyer Division 20 (replaced Desdiv 11 on April 3rd-4th, 1942)

Amagiri, Asagiri, Shirakumo, Yugiri

Second Submarine Squadron (Operational area Bay of Bengal, Sumatra, Java)

I-2, I-3, I-4, I-6, I-7

MARCH 30

“Our fleet, with its line of battleships, was a noble sight such as I had not seen since my days as a midshipman in 1918’.”

Under no illusions as to the effectiveness of half his force, Admiral Somerville set sail from Colombi in Warspite with Formidable, Cornwall, Enterprise, Caledon, Dragon and five destroyers (Nestor, Panther, Paladin, Hotspur and Express ).

Already enroute to the rendezvous point was Vice-Admiral Willis. His flagship Resolution and the rest of the "R"s had left Adu Atoll shortly before midnight, with Indomitable and nine destroyers in company.

However, the composition of the Japanese strike force was not known. Once a comprehensive sighting report had been made, Somerville could judge whether or not the odds were in his favour.

Once his forces merged, the ships could be reshuffled into into his planned “Fast” Force A and “Slow” Force B.

Only HMS Dorsetshire remained behind: She was partway through a necessary engine refit. Her crew, however, was frantically working towards returning her to service.

No sightings were reported. No new intelligence was received.

MARCH 31

The roaming Catalinas reported Japanese submarines on the surface some 360 miles east of Colombo.

Somerville judged these were to act as both reconnaissance and an anti-surface screen for an advancing carrier force.

To maintain radio silence, an Albacore was flown off from Formidable to ask the RAF to establish a patrol in the area of the sightings, over-and-above the existing Catalina flights.

The two groups the Eastern Fleet met up during the afternoon. Signal lamps flared and flags were flown. Gradually the ships moved into their new formations.

Sunset was at 1809 hours. Somerville had to keep his force hidden until then. Only under the cover of darkness could he move eastward to take up a more favourable flying off position for his strike aircraft.

But no report of a sighting of the Japanese fleet had been received.

Somerville resolved to make an all-out effort to find the Japanese this night, ranging as far as the estimated ideal Japanese flying-off position.

The fast ships of Force A motored steadily northwards until dark, then swung about on a course of 80 degrees at a cruising speed of 15 knots. Radar-equipped aircraft were sent to the south and east, adding their scope to those aboard Warspite and the cruisers in scouring the night.

Force B, meanwhile, struggled to maintain a covering position some 20 miles westward.

Somerville could, however, have been in a much better position.

Nagumo's aircraft had this morning struck the radio facilities on Christmas Island. An allied submarine had even sighted his ships as they passed by.

None of this was relayed to the Eastern Fleet.

APRIL 1

By 0230 the anticipated Japanese flying-off position had been reached.

Nothing was there.

Course was set to the south-west and Somerville’s two forces withdrew, joining together at their distant daytime waiting position at 0800 hours.

During the afternoon, HMS Dorsetshire joined. Her crew had hastily returned her engines to service.

Nagumo, in the meantime, was maintaining a fuel-efficient pace. He had decided to delay his attack further, from April 4 to Easter Sunday (April 5). He felt that - just as the Americans at Pearl Harbor - the British would be less alert and attending church.

For Somerville, it was more of the same: No sightings were reported. No new intelligence was received.

APRIL 2

As dusk fell, Somerville was forced to make a decision. After three days of alternating between his day and night stations, anxiously awaiting sighting reports, the more venerable ships of his force were getting low on fuel – and water.

The R-class battleships had totally inadequate condensers to provide their own engines with a constant, clean water supply – yet alone their crew. Their tanks were beginning to run dry.

Optimal moon conditions had almost passed. The likelihood of a Japanese attack seemed greatly reduced.

At worst, the Japanese were playing a game of cat-and-mouse, waiting for his fleet to return to harbor where it would be vulnerable to another Pearl Harbor and Darwin style attack.

At best, the Japanese had aborted their raid.

Most likely: It had all been a false alarm.

That night, Somerville again conducted an eastward sweep – though not as deep as before. By 21.00, nothing had been found.

Somerville ordered his ships to withdraw to Adu Atoll to restock.

Unknown to all, Vice-Admiral Nagumo’s force was now in the Indian Ocean, some 500 miles off the coast of Sumatra.

For the Eastern Fleet and Colombo, no sightings had been reported. No new intelligence was received.

Hugh Popham in Sea Flight: The Wartime Memoirs of a Fleet Air Arm Pilot

Now, at last, it seemed that action was upon us. We joined Formidable and the remainder of the fleet, and cruised up and down to the south of Ceylon at constant readiness. The ship was electric with rumour. And nothing happened. On April 2nd, the fleet turned south and steamed to Addu Atoll, a remote ring of coral six hundred miles from Ceylon, and within a stone’s throw of the Equator. I was in the air when we approached it, and, according to the ship’s navigator, crossed and recrossed the line half a dozen times while waiting to land-on, which must be a record of some sort. It was a place that on appearances alone would give a travel-agent a rush of adjectives to the head: white coral beaches, waving palms, a cobalt sea changing to jade-green inshore, and a sun like an ultra-violet-ray lamp. The reality was rather different. The sea inside the lagoon was tepid and brackish; the white beaches were floored with chunks of coral as jagged as a kitchen-knife that cut one’s skin to ribbons and started sores it took months to heal. The heat was inescapable, and the flies stuck to one’s skin like limpets to a rock.

APRIL 3

“It was a dreadful desolate place. Nothing there, barren as anything. Some people called it “Scapa with palm trees”.”

Admiral Somerville's fleet steadily made its way westward.

At 0520 the destroyer HMS Fortune was dispatched from the fleet to assist the SS Glen Shiel which had reported being torpedoed.

A short time later, the heavy cruisers HMS Dorsetshire and Cornwall were instructed to return to Colombo. Dorsetshire needed to continue her urgent refit. Cornwall was scheduled to escort the convoy SU4 to Australia.

Also in the back of Somerville’s mind was the need to prepare for the Admiralty’s Operation IRONCLAD – the invasion of Diego Suarez, Madagascar. This was scheduled for May 5. It was considered a vital move to prevent the Vichy French from handing over its port facilities to the Japanese in the same way they had for their Indo-China territories. Any hostile force base on Madagascar would be ideally position to deny all traffic in the western Indian Ocean and even raid deep into the South Atlantic.

To that end HMS Hermes and HMAS Vampire were dispatched to Trincomalee to undergo boiler cleaning.

Somerville felt his decision was sound: No sightings were reported. No new intelligence was received.

Admiral Nagomo’s force, however, was at this time refueling at sea before swinging on a westerly course at a speed of 20 knots.

APRIL 4

“... we were saved from this disaster by an airman on reconnaissance who spotted the Japanese fleet and, though shot down, was able to get a message through to Ceylon which allowed the defending forces there to prepare for the approaching assault; otherwise they would have been taken by surprise.”

Counter to Somerville’s speculation, Nagumo had simply been operating to his own flexible schedule.

His fleet had departed Kendari in Indonesiaon March 26 and entered the Indian Ocean via an unexpected route through the Ombai Straits.

But Nagumo had himself received no sighting reports of the British Eastern Fleet. This did not overly concern him. He was supremely confident in the superiority of his force.

He was certain he retained the advantage of complete surprise.

Nagumo had modified his plans to attack on the morning of the 5th: Easter Sunday. He believed many defenders would likely be attending church.

Meanwhile, Somerville’s fleet was dispersing. Early that morning, Dorsetshire and Cornwall had again taken up their berths at Colombo. Dorsetshire’s crew began preparing ship for already delayed maintenance and the fitting of new anti-aircraft guns and radar sets.

It was about 1600 (4pm) when a reconnaissance aircraft radioed it had spotted the Japanese carrier group 360 miles south of the southernmost tip of Ceylon.

This Catalina was flown by Squadron Leader L.J Birchall. He had flown out of Koggala lagoon at 6am that morning, with enough fuel aboard to linger over his patrol grid (starting some 250 miles south-east of Ceylon) until daybreak on the 5th.

After 10 hours in the air, the Catalina’s crew sighted a smudge on the southern horizon. Investigating from a height of 2000ft, Birchall saw a fleet formation including carriers, battleships, escorts and supply ships.

He knew it must be the Japanese fleet.

Nagumo’s flagship, Akagi, along with Shokaku, Zuikaku, Hiryu and Soryu, was taking station at a flying-off position some 200 miles from Colombo. This was some 160 miles south-west of where Somerville had expected Nagumo to be four days earlier.

Turning north under full power, it was already too late for the Catalina and its crew.

Six Zeros from Hiryu had been sent to intercept.

The Catalina’s radio operator managed to get off a sighting report. But before he could finish his regulation two repeats, cannon shells from the fighters began to rip through the airframe – demolishing the radio.

The fight lasted just seven minutes. Some 350 miles from land, with dusk settling in, Birchall was forced to put his Catalina down in the ocean.

Birchall would later recall:

““As we got close enough to identify the lead ships we knew at once what we were into but the closer we got the more ships appeared and so it was necessary to keep going until we could count and identify them all. By the time we did this there was very little chance left... All we could do was to put the nose down and go full out, about 150 knots. We immediately coded a message and started transmission ... As the Zeros flew in and started to attack, the Catalina began to break up in the air. We were halfway through our required third transmission when a shell destroyed our wireless equipment and seriously injured the operator; we were now under constant attack. Shells set fire to our internal tanks. We managed to get the fire out and then another started, and the aircraft began to break up. Due to our low altitude it was impossible to bail out, but I got the aircraft down on the water before the tail fell off. All the time we were landing and immediately thereafter we were under constant enemy strafing.”

Six survivors were taken aboard the destroyer Isokaze where they were beaten and interrogated.

The single transmission was, fortunately, enough. It was received - though somewhat garbled - and rapidsly shared among all Colombo’s defenders.

Flash warnings were issued.

Admiral Somerville was caught off balance. The remnant of his fleet was only just entering Addu Atoll, 600 miles away.

Most of the ships of his fast Force A could sail immediately – about midday - but not the light cruisers Emerald and Enterprise. These could not complete refueling until midnight.

Force B would not be ready until the following morning. Even then the R-class battleships would remain short of water: There was no freshwater tanks at Addu Atoll. A water-carrying ship had been delayed. And their own condensers had not yet caught up.

Back at Colombo, the Commander-in-Chief of Ceylon, Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton, ordered all ships to put to sea immediately. All ground and air forces were instructed to be at action stations by 3am.

He was convinced an attack would unfold early the next morning.

In Colombo harbor, HMS Cornwall made steam as Dorsetshire scrambled to get herself back into an ocean-going state. They had received orders to meet up with Admiral Somerville’s Force A as it raced back towards its pre-arranged staging point some 250 miles south of Ceylon.

Around them, 48 merchant ships weighed anchor and scattered to the west and northwest. Some reports indicate a further 21 remained in harbor, unable to sail.

Another Catalina, piloted by Flight Lieutenant Graham of 205 Squadron, was ordered to make its way towards Squadron Leader Birchall’s sighting report.

At midnight, the remaining fast ships of Somerville’s fleet set out from Addu Atoll and quickly made their way eastward.

All the British could do now was wait.

APRIL 5

“Damn and blast it looks as if I’ve been had...here I am miles away and unable to strike.”

With translation annotations, this is an original depiction of Nagumo's Kido Butai daytime cruising disposition.

Shortly before 1am came confirmation of Birchall’s report: Graham signalled he had sighted a destroyer 200 miles south-east of Ceylon. The report was not repeated. Nothing was ever seen of this Catalina again.

A third Catalina, piloted by Flight Lieutenant Bradshaw of 240 Squadron, was dispatched.

Flying low to evade radar (the allies did not know at this time that Japan did not have this technology), Bradshaw sighted a large formation of aircraft overhead.

Being so close to Ceylon, Bradshaw assumed them to be friendly – perhaps from Formidable and Indomitable. He did not break radio silence to report their presence.

Bradshaw was not seen by the Japanese as they flew past: His Catalina was lost among the haze and waves.

An Aichi E13A recon seaplane launches from the portside catapult of the Myōkō-class cruiser Ashigara

The Catalina’s crew soon spotted the battleships and cruisers of Nagumos’ force which had taken up protective stations ahead of the carrier body just 200 miles south of the island. The warships had just launched their own patrol seaplanes, with instructions to roam 250 miles to the west and south – searching for the Eastern Fleet.

Stayling low, Bradshaw had hoped to remain unseen. Soon, however, shells from warships began exploding about his wave-top hugging aircraft.

This was not so much of an attempt to shoot him down as it was to notify fighters of the CAP as to his presence.

HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire had picked up Bradshaw’s urgent warning. Realising the enemy was just 150 miles to their east, the two ships worked up to maximum speed (27.5 knots due to Cornwall’s tired engines).

But Nagumo, even though he now suspected his fleet had been located, still expected Somerville’s warships to be in harbor at either Colombo or Trincomalee.

And his strike force was already on its way.

Unexpected Surprise

A Catalina sighted six aircraft at 0534, headed towards Colombo. It incorrectly identified these as Fulmars and did not send in a sighting report. Had it done so, it would have given Colombo 50 minutes warning.

Sx Fulmars from 803 Squadron was patrolling an established track coast-to-coast to the south of Colombo. It failed to sight the formation of Japanese aircraft as it was flying over water along the south-west of Ceylon.

The mobile radar station close to Colombo should have been able to give defenders 20 minutes early warning . For whatever reason, this didn't happen.

Excuses ranged from lax shift changes to scheduled maintenance and poor positioning among the hills. Other accounts argue the unit had not yet had time to establish its equipment.

Robert Stuart in an article for the Royal Canadian Air Force Journal (Vol3 No.4 Fall 2014) argues the radar station's crew had arrived on March 18, and its equipment on March 22. Established at the Royal Colombo Golf Course, it reportedly became operational as early as March 25.

Stuart cites RAF reports as showing the radar was poorly positioned, with heavy and permanent interference from nearby hills, giving it a detection range of just 60 miles (54 miles of which was south of Ceylon). At best this offers just 17 minutes warning. (Stuart points out the similar set used at Trincomalee picked up approaching Japanese formations at 91 miles)

But Colombo was alert, if not ready.

Two patrols were already in the air. One was of two Hurricanes from 30 Squadron. The second was the six Fulmars of 803 Squadron. Both formations had been flying just below the cloud line at 2000ft, but were now headed home after an uneventful dawn patrol.

About 7.15am, the formation of 127 Japanese aircraft crossed over the coast at about 8000ft.

They included 53 bomb-carrying B5N Kates (18 from Soryu, 18 from Hiryu and 17 from Akagi). There was aslo 38 D3As (19 from each of Shokaku and Zuikaku). Their escort was 36 A6Ms (9 from each of Akagi, Soryu, Hiryu and Zuikaku)

OPENING MOVES

Blundering into the Japanese as they arrived over Ratmalana was a flight of six torpedo-laden Swordfish. These were under orders to fly from Trincomalee to Ratmalana where they were to refuel before heading out in search of the Japanese fleet. Following regulation line-ahead approach procedures down a narrow pre-designated approach corridor at 2000ft, the ‘Stringbags’ were inherently vulnerable.

Fuchida called in his fighter wing to dispense with the venerable naval bombers. Initially, the Swordfish believed the six approaching aircraft to be Hurricanes. Recognition flares were fired, and code letters flashed by lamp. Too late did the Swordfish crews recognise the profiles to be those of Zeroes. Burdened by their torpedoes, the biplanes were unable to take meaningful evasive action. All six were sent into the ground or sea.

Among those killed was Sub Lt Anthony Beale who had been awarded a DSC for an attack on the German battleship Bismark.

A flight of Japanese bombers attacked Ratmalana airfield and railyards. Fuchida was a passenger in one of the B5N Kates.

The airfield's radio and telephone network went dead (the operators having abandoned their posts), so the fighters were unable to coordinate their defence. No. 30 Squadron, having completed its morning patrols, was caught on the ground. The Hurricanes would have to claw their way up to 8000ft before they could tangle with the bombers. But to get there they had to evade the escorting Zeros.

The 30 Hurricane IIs, five Is and six Fulmars of 803 Squadron were scrambling to get off the ground at Ratmalana. Many quickly quickly fell prey to the swooping Zeroes.

Any aircraft, regardless of its performance, was at its most vulnerable immediately after take-off. The aircraft were simply too slow and low to manoeuvre.

Sub Lt W.H. Anderson recalled:

"Just as we reached the airfield perimeter by truck, the second wave of aircraft were arriving at much lower height, dropping what appeared to be enormous bombs, strafing the airfield, and taking an incredible toll of the Hurricanes as they scrambled ahead of us.

One of the only TAGS to reach the airfield in time for the scramble jumped into the back of my Fulmar and used the only weapon available - a Very Pistol and cartridges - to frighten off any Jap getting a bit close!"

The dogfight was short but intense. Not knowing the formidable low-speed characteristics of the Japanese Zero, the RAF and FAA fighter pilots sought to engage in the same way they had significantly less manoeuvrable German and Italian fighters.

Lt Mike Hordern recalled:

"We were caught on the ground for a start, and not many of us even got airborne. A Petty Officer with a sub-machine gun leapt in the back of my aircraft and I believe even fired it with wild abandon!

I was on my own and saw a number of enemy aircraft circling over the sea - possibly reforming or in defensive orbit against some other aircraft. I approached through broken cloud cover, at about 5000 feet, and made one pass before breaking off at high speed and seeing one aircraft burning on the surface of the sea.

I was credited with one Navy 96 (A6M2 Zero) shot down - seen and confirmed by a Naval officer standing outside the Mount Lavinia Hotel."

Desperate defence

“Having received no warning and finding the enemy aircraft overhead we took off, and climbed for the harbor as being the most likely point of enemy attack”

Pilot Officer Jimmy Whalen, RCAF, one of the RAF 30 Squadron defenders of Ceylon, walks from his Hawker Hurricane IIB “RS-W” on April 5, 1942, the day after he claimed three Japanese aircraft shot down. Source: Imperial War Museum

A little further north, the port of Colombo was awake to the threat.

Unlike Pearl Harbor and Darwin, its defences were at least alert.

An intense anti-aircraft barrage blanketed the sky above the harbor.

The Japanese strike force made its way to the dockyards, confident their covering fighters would deal with the British. The Val dive bombers were surprised to find it almost empty.

HMS Tenedos, a destroyer undergoing refit, was hit. Her stern was blown away. The armed merchant cruiser Hector was bombed and set on fire. Both soon settled on the bottom.

The submarine tender HMS Lucia was damaged though the submarine HMS Trusty, taking on torpedoes for her next patrol, was undamaged. The freighter Benledi, unable to get underway due to ongoing repairs, was also damaged. While the naval repair shops were destroyed, the port facilities remained largely untouched.

But 14 Hurricane IIb’s of 258 Squadron had scrambled from their converted racecourse. Their makeshift airfield had not yet been seen. The Hurricanes rose to intercept the Japanese bombers even as they fanned out to attack their individual targets – harbor shipping, rail yards and warehouses.

258 Squadron Leader Fletcher recalled:

"Having received no warning and finding the A/C overhead, we took off and climbed for

the HARBOUR as being the most likely point of enemy attack. When we arrived, we

found that the Bombers had commenced their attack, and there was a strong force of

enemy fighters as top cover, and considerably above our formation. I decided to attack

the Bombers in the hope that it would impair the efficiency of the enemy attack. I realized

that this would put the enemy fighters in a strong position. We continued to attack the

bombers for as long a period as possible, though this resulted in rather heavy losses

inflicted by enemy fighters...

“We did a climbing turn towards the harbour; I was still hoping against hope to get above them but if not, a head-on attack against the formation might be possible. Suddenly a couple of Jap bombers dived down through a gap in the clouds, very close to us. Obviously dive-bomber attacks had started. We were still much below the bombers so I had a difficult decision to make. It looked as if we had been spotted. There was (sic) masses of cloud cover about and if we continued climbing, we might get the precious height we needed. On the other hand, by that time the bombers would have done a lot of damage; we would be seen by the Zeros sooner or later and would be mixing it with them instead of getting at the bombers. I decided to go after the bombers, shouted “Tally-ho” and turned into a dive through a cloud between us and the gap through which the Japanese were diving. Some of the formation lost me in the cloud but two or three were still with me when we broke cloud and were in a good position to attack. From then on it was every man for himself.”

Two Vals were claimed as killed as they dived through the rising Hurricanes. But the tables were soon turned as the escorting Japanese fighters arrived. The 258 Squadron Hurricanes attempted to engage in a turning fight: Nine were quickly knocked from the skies.

258 Squadron Leader Fletcher had his Hurricane disabled by defending anti-aircraft fire before two Zeros pounced on his tail. He was able to bail out.

The remaining aircraft from 30 and 258 Squadrons managed to regroup and returned to the fray.

The surviving RAF pilots, by this stage, had begun to identify their aircraft's strengths and their opponent's weaknesses.

"I was scrambling with the squadron, and once again warning was given when the enemy was almost overhead. Over the harbour I became involved with two enemy fighters and a light bomber and eventually claimed the bomber as destroyed. It was extremely unwise to mix it with 'Zero' fighters at low altitude and I had to break away from the main centre of the activity to gain height and come in at the top again.

By this time the action had developed into a series of quick diving attacks as the Japanese force retreated out to sea."

By 8.35am, the action was over. The Japanese aircraft streamed out to sea, returning to their home ships.

The oblivious flight of Fulmars which had earlier seen the Japanese cross the coast was now returning from patrol. Again they believed the ragged formation to be FAA aircraft from Indomitable and Formidable. Only when they approached their airfield did they realise what they had escaped:

Observer Sub Lt Roy Hinton:

"Arriving back at base it was so obvious that all hell had been let loose only minutes before. It transpired that all the wireless operators at Ratmalana had sought shelter as soon as the first bombs were dropped."

Counting the cost

“We invented on the spur of the moment an obvious tactic for survival. We flew at wave-slapping height and then, with all the crew placed at vantage points for look out, pulled briefly up to 100 feet. If no Japanese masts broke the horizon we went down to nought feet again and flew on to where the distant horizon had been. Here we repeated the exercise. In this way we successfully shadowed the Japanese, never, after the initial identification, seeing more than the tops of their masts...”

The Japanese believed they had shot down 39 RAF fighters and damaged another 11. Actual RAF losses reported were 21 Hurricanes downed, two of which were repairable. Japanese pilots also claimed eight Swordfish, though the number was actually six.

258 Squadron claimed four destroyed, one probable and four damaged. The FAA claimed one kill - but had lost four out of its six Fulmars. 30 Squadron's tally was 14 kills, six probables and five damaged. Ground AA gunners claimed five.

In all, Britain claimed 24 kills. Japan would only ever publically admit to losing five aircraft.

While most Japanese records of the attack appear to have been lost, accounts such as Bloody Shambles by Christopher Shores gives the tally as six D3A destroyed and seven damaged, along with one A6M and three damaged, and five B5N damaged.

Civilian casualties on the ground amounted to 85 dead and 77 injured.

In the immediate aftermath, Colombo only had a handful of fighters available to repel any follow-up attack. 30 Squadron had seven Hurricanes, while 258 had three MkIIbs and one MkI. About eight Fulmars were also active.

Fuchida was aware of this weakness: He urged Nagumo to rearm the reserve aircraft for a follow-up strike on the airfields.

Whatever the actual Japanese losses, it was a costly day for the RAF and FAA.

Admiral Layton was particularly scathing of the performance of his Fulmars and Swordfish.

‘Fleet Air Arm aircraft are proving more of an embarrassment than a help, when landed. They cannot operate by day in the presence of Jap fighters and only tend to congest aerodromes.’

Counter-attack

The Blenheims of 11 Squadron had escaped the Japanese attack. Just a week earlier, they had been redeployed to the Racecourse airfield.

Ten Blenheims were at the alert, fueled and loaded up with 500lb semi-armour piercing bombs. But they were forced to wait until all scrambling 258 Squadron Hurricanes were out of the way.

The Blenheims managed to get into the air at 8.30am, hoping to catch Nagumo’s carriers in the midst of landing-on his returning strike force.

Wing-Commander A.J.M. Smyth, however, failed to find the Japanese fleet due to heavy cloud. He was forced to return without dropping his bombs.

Meanwhile, Nagumo’s force had been thrown into disarray.

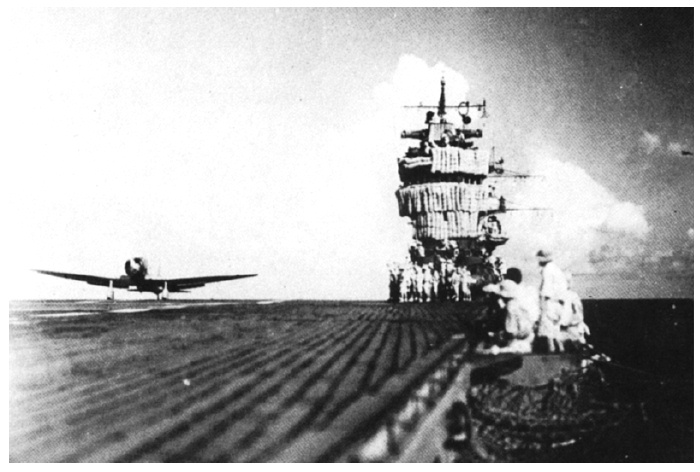

Aircraft prepare for take-off aboard Akagi.

“At 1030 the fighters on deck were put at instant readiness, pilots strapped in. We sat there, sweltering, fingers on the starter button, muscles aching with effort and waiting. There were enemy aircraft on the radar screen.”

Confusion

About 10am one of Tone’s seaplanes had reported sighting two destroyers to the north-west of the main fleet travelling the south south-west at 25kts. It warned of an impending surface attack.

And the carriers were only just starting to receive their aircraft.

Worse, the Japanese covering force of battleships and cruisers had been left some 40 miles to the south east: The carrier group had been steering into the wind at 26 knots.

Nagumo was put in a bind: It was a similar situation to what he would later find himself in at Midway.

He had kept back a strike force of bombers for just such a situation.

But Fuchida had already advised Nagumo to rearm his ready anti-ship aircraft for a follow-up attack on Colombo.

Nagumo had ordered their rearmament at 0853.

Now he had aircraft low on fuel, and some damaged, urgently needing to land.

His returning pilots had reported that the Eastern Fleet had not been in Colombo harbor. Were these two destroyers part of its advanced screen?

Then, Tone’s seaplane updated its initial report: Instead of two destroyers, the warships it was shadowing were two heavy cruisers.

HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire.

Both were now well within range of the carrier’s bombers.

Fuchida ordered the urgent recall of all his remaining bombers over Colombo, leaving the Zeroes to deal with the defenders.

He also had to reverse the rearmament order for his dive bombers. This was done at 10.23.

Hugh Popham: Sea Flight: The Wartime Memoirs of a Fleet Air Arm Pilot

The exact size and composition of the fleet was still not properly known: only that it was there, five hundred miles to the north-east of us, steering westward, and that it contained one, or more, carriers.

That night, as we steamed north, a striking force of Albacores, armed with torpedoes, was ranged, with their crews at readiness. As dusk deepened swiftly into darkness, the ship herself seemed to tremble with a strumming nerve of anticipation. Not many people slept. The knowledge persisted past the brink of waking: a Jap carrier-force was approaching Ceylon: we were on our way to intercept. Our chance had come at last.

We were at Action Stations before dawn, hurrying up to the flight-deck almost as if the enemy might be hull-up ahead, almost as if we might be missing something. There was no news, nothing to be seen. We rushed down to breakfast in ones and twos, lifebelts and anti-flash gear near at hand, and hurried back on deck. All was still and expectant. Pilots, observers, air-gunners, with their Mae Wests unbuttoned and their helmets hanging round their necks, moved restlessly about the deck.

“For Christ’s sake, let’s get at the little yellow bastards,” Jock said. “What are we waiting for?”

What were we waiting for? Instead of driving northwards at full speed, we were dawdling about on the leisurely swells. We began to get edgy with impatience.

A portion Nagumo's reserve force of Val dive-bombers eventually took flight at 11.30am. Their instructions were to shadow the cruisers until reinforcements arrived. This happened at noon.

Meanwhile, the Kates and Vals of the Colombo had been streaming back to the fleet. The Zeroes they left behind had to find their own way home.

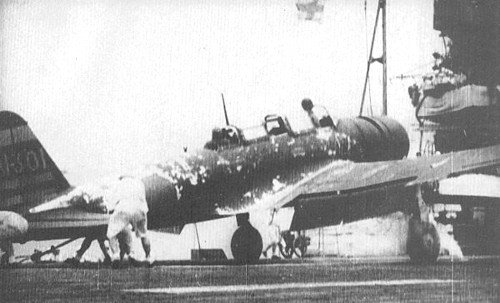

Aircraft ranged on Akagi's deck ready to strike at the heavy cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire, April 5, 1942.

Hammers on eggshells

“One point which had escaped the notice of everyone...was the range and performance of the Japanese naval aircraft...[W]e gave them the same performance as our own, but it later transpired that we had sadly underrated them. Actually, they had nearly double our performance. It is not surprising therefore that when next day [5 April] we sighted the first Japanese ‘shadower’ on the horizon astern, we had no idea at the time that they could possibly reach out so far, otherwise the R/V [the rendezvous with Somerville] would have been placed even further to the west.”

HMS Dorsetshire and Cornwall continued to race southwards. They hoped to be under the fighter umbrella of Formidable and Indomitable by 2pm and to rendezvous with Somerville by 5pm.

The first Japanese reconnaissance aircraft had been spotted by Cornwall’s lookouts about 11am, passing some 20 miles behind the British ships. Later, a second was detected on radar as it loitered near the horizon. Then, about 1pm, a large number of echos indicated a force of aircraft was nearby.

Was this Formidable and Indomitable’s CAP?

But the cruiser captains were cautious, and closed up to action stations regardless of their doubt. They even took the unusual action of breaking radio silence to report to Somerville the location of their ships, and the likelihood of an enemy air attack.

The strike force of Vals was led by Lieutenant-Commander Takashige Egusa, Air Group Commander of Soryu’s wing. His pilots had all been carefully trained to sink the flat-tops of the US Pacific Fleet during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In total, the strike included 18 Vals from Soryu, 18 from Hiryu and 17 from Akagi.

Their skill was immediately evident for the two heavy cruisers.

Despite the radar warning, the approaching Japanese had not been sighted against the glare of the clear sky above the ships.

This was no accident.

The Vals, operating in flights of three, had taken the time to position themselves up-sun. This happened to be directly ahead of the speeding cruisers. Being of 1920s design, neither cruiser had anti-aircraft guns that could fire directly forward.

Hugh Popham in Sea Flight: The Wartime Memoirs of a Fleet Air Arm Pilot

At 1030 the fighters on deck were put at instant readiness, pilots strapped in. We sat there, sweltering, fingers on the starter button, muscles aching with the effort of waiting. There were enemy aircraft on the radar screen. A W/ T message had just been received from Dorsetshire and Cornwall— those dignified symbols of an obsolete Pax Britannica—“ We are being attacked by enemy dive-bombers.”

Then why weren’t we airborne and on our way? For Christ’s sake, why?

A last message from the two cruisers as they went down, and we raged and blasphemed with frustration. Commander Flying was bombarded with the demand, and could only answer: the Admiral says no.

All day it was the same: the sour anger of enforced inaction, of a sapping impotence.

Rumours filtered through. Colombo had been bombed. Then why, and again, why, weren’t we there?

For forty-eight hours longer we steamed in desultory circles, in a state of readiness that had long since become a mockery. Just our luck, we said bitterly, to belong to the fighter-squadrons that never fought. The T.B.R. boys were equally galled. The thought of an enemy fleet just over the horizon, simply waiting to be torpedoed, was too tantalising to be borne.

HMS Warspite and Indomitable watched silently. Their radar operators also had detected the formation of Japanese bombers at a range of some 84 miles to their north-east. The blips soon faded away - no doubt as they initiated their dives.

Closed up at action stations and fully ready to repel air attack, at 1340 Dorsetshire’s lookouts saw the first Japanese bombers directly overhead and opened fire.

The aircraft dived – on Cornwall just a mile to port.

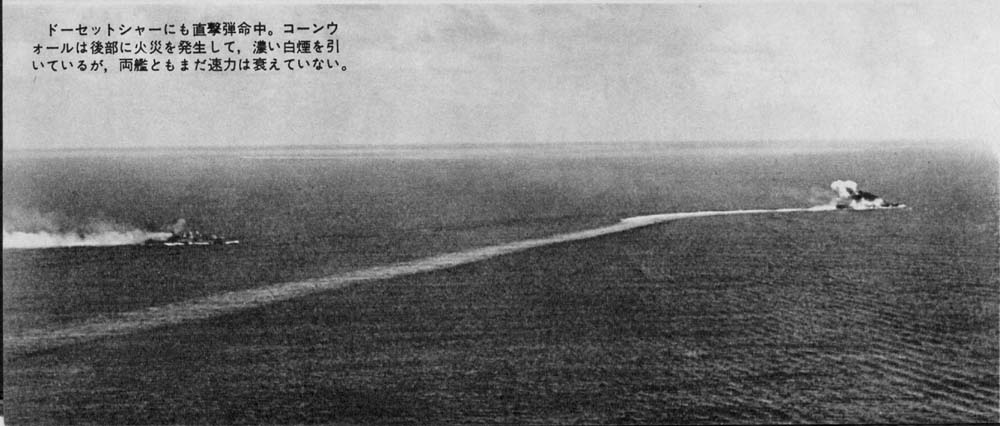

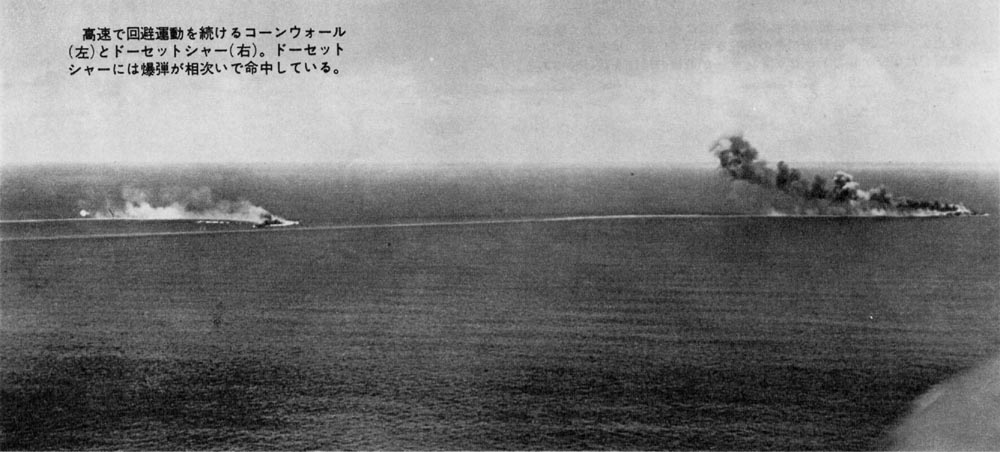

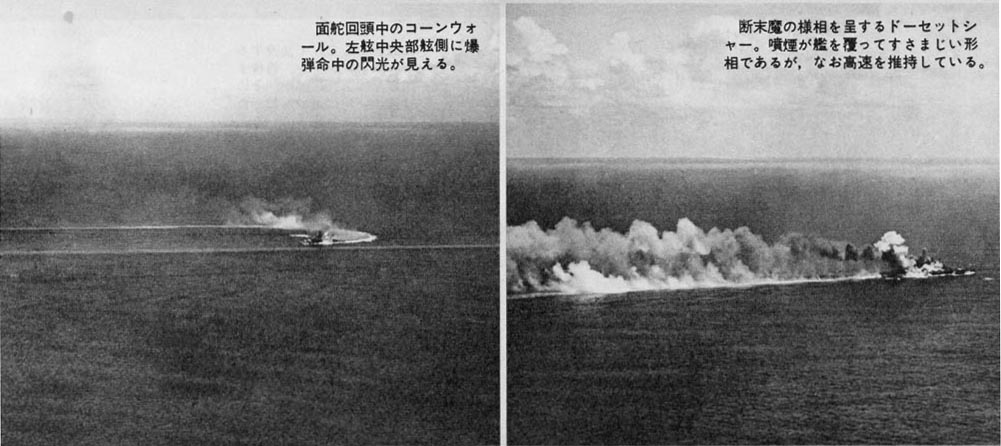

At the same time a second flight of three aircraft began their attack on Dorsetshire. Despite an urgent turn to starboard, all three bombs plunged through her decks. Her rudder was jammed, the engine and boiler rooms hit, the ship’s catapult ablaze and the radio room smashed – all within the opening minutes, Dorsetshire lurched to a stop. Then a bomb hit one of her magazines.

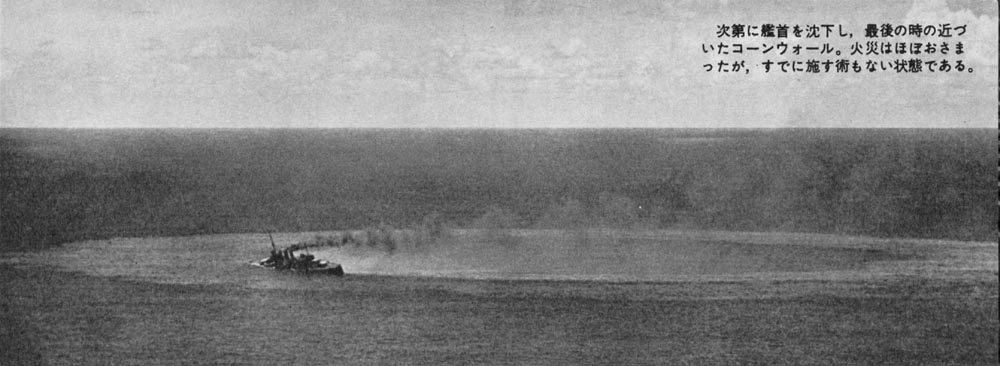

By 1348, Dorsetshire’s bow lifted as her stern began to slip beneath the waves. In all, she’d been hit by 17 500lb bombs.

Cornwall followed shortly after. The first bomb had struck astern. Attempting to evade with a swing to starboard, several of her anti-aircraft gun mounts were obliterated as more bombs rained down.

Sub Lt Popham recalled:

"A W/T message had been received from Dorsetshire and Cornwall: 'We are being attacked by enemy dive bombers.' Then why weren't we airborne and on our way? A last message from the two cruisers as they went down, and we raged and blasphemed with frustration. All day it was the same: the sour anger of enforced inaction, of a sapping impotence.

The TBR boys were equally galled. The thought of an enemy fleet just over the horizon, simply waiting to be torpedoed, was too tantalizing to be borne."

* Pictures originally attributed as being uploaded by Bill Somerville on the J-aircraft.com site. Unfortunately I am unable to find the original post to link to.

First Lieut. Geoffrey Grove later described his recollections of the attack.

“We watched the planes like hawks, and as the bombs showered down, we flung ourselves down on our faces. If the hit was close by, you were bounced like a ball. We had three hits almost directly under us and for one of them I was standing up and was enveloped in a great sheet of flame. I thought it was the end of me but my clothing saved me and I was unhurt. We took something like fifteen hits in about seven minutes and the poor old girl took on a bigger list than ever and started to settle. When I could do no more up top, I went below to help put out the fires and throw red-hot ammunition into the sea. We got all the fires out quite easily. By this time the ship was obviously sinking and some of the men were launching the floats.”

Japanese reports are cited as saying 13 bombs were dropped on Cornwall, with 11 direct hits. The heavy cruiser went under, bow first, at 1400

Egusa’s dive-bomber crews had set a record for bombing accuracy: Every bomb either struck the heavy cruisers, or burst right alongside.

Spotted some two hours later by a Swordfish sent to investigate the scene, a rescue destroyer would be recalled by Somerville under the mistaken belief the Japanese main force was nearby.

Contact

TAG L/Air Gordon Dixon recalled (in Bloody Shambles Volume 2):

"We sighted the Jap fleet - we could see the outline of the carriers and the battleships. Sub Lt Jaffray gave me a signal to send. A simple message, repeated twice, indicating the sighting. It was while sending this message that the 'Zero' made the first attack. At this time we would have been flying at 3000 feet.

At once Grant-Sturgish dived to sea level. The 'Zero' then made a frontal attack. This we evaded by swerving side to side. The pilot fired his forward gun. It then attacked from the rear. I stood up in the cockpit with the Vickers GO, and when the 'Zero' opened fire, I responded with a burst, while Grant Sturgis did a tight turn towards the fighter.

It was during the second attack from the rear that I was hit in the left forearm and the left hip. The fighter engaged us for about 15 minutes, making four attacks from the rear and three frontal ones. All the time we were at sea level.

The Vickers gun had a very small bag to collect the spent cartridges, and if this got too full the gun jammed. To avoid this, I removed the bag: consequently, when firing, spent cases were flying all around the cockpit.

We finally arrived back at the carrier and Jaffray fired a Very pistil, and we landed straight away. The Albacore had been hit by about 40 bullets."

Four Albacores of 827 Squadron aboard Indomitable were sent aloft at 1400. They ranged 200 miles to the north-east of the British fleet as it gingerly advanced. At 3pm, one of them sighted the wreckage of the two cruisers – and radioed a report.

Just 15 minutes later, the same pilot – Sub Lieutenant Streathfield – was shot down after sighting the main Japanese formation. His crew had not had time to send a full report. All three aboard were killed.

The Eastern Fleet and Nagumo’s strike force were just 180 miles apart.

With just four hours of daylight left, it was the most dangerous moment of the entire operation.

But neither commander knew where the other was.

Had Sub Lieutenant Streathfield been able to get off a detailed report, the direction of the war could have been turned on its head. Somerville could have been able to set course for his desired night intercept.

The outcome of such an engagement was by no means certain – for either side.

But Somerville was left frustrated.

Without accurate details of location, course and speed, he could not calculate the necessary path to guarantee a safe night launch of a radar-guided Albacore strike, followed up by an attack by his fastest warships.

He wasn't even certain of the enemy's fleet composition.

Then, at 1817, a battered 827 Squadron Albacore made it back to Indomitable's deck. While souring the western edge of Somerville's search area, it had stumbled over Nagumo’s ships. Sub Lieutenant Grant-Sturgish had been forced to dive while under attack from a Zero. Weaving between the wave tops, the Albacore escaped: The Japanese aircraft had used up all its ammunition and pulled away.

With a wounded airman, a bullet through the radio and another through a tyre, Grant-Sturgis had to put his vibrating plane back on deck before he could make his report. This had taken two hours of tense flying. Touching down, the Albacore slewed heavily and almost went over the side.

“Out of a confused story it seemed that Grant-Sturgis had indeed caught a glimpse of two enemy carriers and almost immediately been attacked by a Zero. He had been torn off a strip for not staying to shadow the enemy - TAGs were obviously considered expendable and Zeros just a minor nuiscance.”

CLEARED FOR ACTION

“The Hurricanes were taken below and I saw our Albacores coming up on the lift, torpedoes slung and flares on the wing racks. The Tannoy called us to the ready room; you would have thought we were all going to a party. Peter Mortimer told us that Grant-Sturgis had made a sighting and that as soon as the enemy position was confirmed we could expect to make a night attack. ”

Grant-Sturgis reported five Japanese ships - including two carriers - had been seen 120 miles from Force A, steering to the north-west.

Somerville was convinced this was his chance to initiate a night action, so he also changed course to the north-west.

The carriers were already at the ready. Torpedoes had long since been loaded on HMS Indomitable and Formidable's Albacores and the aircraft had been waiting for the launch order, their crews awaiting the loudhailer's call to action.

Observer Gordon Wallace recalls:

Ground crew were milling around as we approached 4C, ranged in the first section on the port side, so we would be one of the first to go in to the attack. I bent down and looked at the torpedo, all 1600 pounds of death reflecting what little light was left. A voice out of the dark said 'You've got a good one there, Sir, see you put it right up one of those squint-eyed bastards!

I climbed in after Oscar and, after switching on the little hooded light, unpacked all my gear and checked the beacon receiver. There was nothing else to do but sit and shiver in the darkness as the aircraft gently rocked on its fat tyres. From my compass i saw that the ship was now on a north westerly course which seemed strange. Acrid fumes from the ship's funnel percolated into the cockpit. I lost count of time and don't remember how long it was before there was a rap on the cockpit door and a disembodied voice said we were packing it in for the night...

So why hadn't we been flown off for our night attack? No one knew.

The Eastern Fleet held a steady north-western bearing. Through the night, (four) radar-equipped Albacores swept an arc to the north.

They found nothing.

Nagumo's force had much earlier actually come within 100 miles of the Eastern Fleet, travelling in a south-easterly direction. It passed quickly beyond reach.

APRIL 6

By now Admiral Somerville had learnt of the second Japanese raiding force roaming the Bay of Bengal. Signals reporting merchant ships under attack by aircraft or surface ships were coming in thick and fast.

In all, Vice-Admiral Ozawa’s cruisers and destroyers had sunk 23 merchant ships totalling more than 100,000 tons.

Somerville had also learnt of the size of the force that had attacked Colombo. Clearly it was vastly superior to what his own carriers could caounter.

A flight of Swordfish were sortied from China Bay at dawn to search for any Japanese ships they could find. Several 273 Squadron Fulmars were in company, as escort, or on reconnaissance flights of their own.

They found nothing.

Nagumo, however, had failed to extrapolate the course of the two British cruisers his aircraft had sunk the day before and had neglected to send a scouting formation along their line of advance.

Instead, he had altered course to the south east the previous afternoon. This was to keep a rendezvous with an oil tanker and its support ships before launching an air strike on Trincomalee.

Both Somerville and the general staff at Colombo believed by now the Japanese carriers could be headed towards Addu Atoll. Somerville resolved to maintain an easterly course to place himself between the Japanese fleet and their home ports.

After some 26 hours in the water, at 5pm, help finally arrived for the survivors of HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire. An aircraft flew overhead, signalling “Hold on. Help is coming”.

Then, at 6pm, the light cruiser HMS Enterprise and the destroyers Paladin and Panther hauled over the horizon. Fighters from HMS Formidable and Indomitable maintained a watchful presence.

In all 1122 men were pulled from the water. The two heavy cruisers had been carrying 1546 between them.

Ken Smith, in Iain Ballantyne, Warspite