“The lampyrinae from which the name was borrowed have the property of emitting phosphorescent light, and if their Fairey-built namesakes were not exactly luminiferous, they were luminaries in the sense that, among shipboard aircraft of their day, the combination of supreme versatility, tractability and reliability that they coupled with performance, handling qualities and firepower was unrivalled. Indeed, the extraordinary amenability that the Firefly was to reveal to an unprecedentedly broad role spectrum was to endow it with a life span of almost a quarter-century.”

FIREFLY OPERATIONAL NOTES

“There was nothing radical about the Firefly. Rather ir represented the synthesis of the Fairey Aviation Company’s years of expertise in combining the demands of the nautical with those of the aeronautical. But if lacking radicality of conceptit was not devoid of the innovatory, not least of its patented Youngman area-increasing flaps.”

Combat Performance:

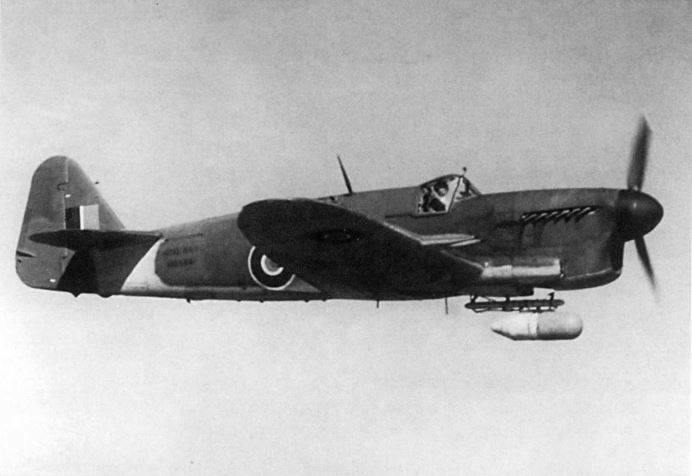

A prototype Firefly displays its Younman flaps.

The Firefly prototypes and early production aircraft had also been put through tactical combat trials. These found the F1 would be suited for use as a long-range escort, strike and night fighting roles – but not as a straight day fighter.

Fairey had been struggling with the challenge all naval aircraft builders faced: How do you create an aircraft with the sleek aerodynamics (and therefore high landing speeds) of high-performance land-based interceptors – yet give it the slow-speed handling necessary for safe deck landings?

Their solution was the hydraulically-operated Fairey-Youngman retractable flap system.

A Firefly FR1 with its flaps in take-off position.

It was, in essence, a precursor to the variable-geometry wing.

The large flaps had four positions. Housed was fully retracted and flush with the elliptical wing. Cruising was extended to one quarter of capacity. Take-off was about two-thirds extended. Landing was fully swing down and out for maximum lift and drag.

Under combat conditions, the flaps could be deployed to “Cruise” to give the Firefly an outstanding turning circle. Testing showed it was more than capable of turning inside contemporary interceptors. It was this manoeuvrability that gave the multi-role fighter its ability to defend itself.

However, the Firefly simply did not have the power of speed or climb to maintain a favourable position against single-seat opponents.

One early Firefly F1 was sent to the United States for tests at a Joint Fighter Conference. Here it was pitted against a variety of US and RN naval fighters, including a captured Japanese A6M2. With its flaps part-way deployed, the Firefly impressed all involved by repeatedly turning inside the legendary Zero.

Test Pilot Eric Brown summarised the Firefly’s chances in his World War II naval aviation overview book, Duels in the Sky:

Firefly 1 Versus Messerschmitt 109G

The Gustav outclassed the Firefly in performance and therefore had the initiative, but once battle was joined the Firefly could give a good account of itself.

Verdict: The Firefly would be no match for the German fighter unless the latter were lured into mixing it, when the Firefly’s turning circle and powerful armament could prove a lethal combination.

Firefly 1 Versus Focke-Wulf 190A-4

The marked superiority of the Fw 190A-4 in virtually every department would give the Firefly no chance of success. The latter could exploit its turning agility to the full, but even that would only delay the inevitable.

Verdict: The Firefly would not be an easy prey for the Fw 190A- 4, but neither would it be difficult—it had no sure escape route.

“The Firefly handled well approaching the deck at 78 to 80 knots (90 to 92 mph), and the view was reasonable, but when throttle was Cut the control column had to be pulled back to counteract a tendency for the heavy nose to drop. The landing gear was resilient enough to prevent bad bounce.

”

FIREFLY F1

“It represented a very real advance on anything that had gone beforre from virtually every aspect; it lacked little of the agility of its single-seat contemporaries and, if unable to deliver level speeds considered spectacular by standards then appertaining, it could trade firepower with its potential opponents on a basis of at least equality and offered significant advances in range and endurance.”

Armament:

In its prototype phase, the Firefly had what was then regarded as a heavy main armament: four 20mm electro-pneumatic Hispano cannon. The inner cannons were fed with 175 round belts, with 145 for each of the outer guns.

But by the time it finally entered service, the four by 20mm configuration had become accepted as the new RAF/FAA standard.

What made the Firefly a success in its role as strike fighter was the capacity to carry two 1000lb bombs. By 1945, fittings enabling it to carry eight 3in rocket projectiles had also been added.

Folding Wings:

Like the Seafire, the Firefly’s folding wings were not motorised in order to save weight. Unlike the Seafire, its wings swung backwards – not up. This gave it ample clearance for low hangar spaces, such as HMS Implacable and Indefatigable.

But the folding process was complicated. It required five men manhandling a large steel rod attached to the wingtip, with another fitting a brace at the fold section. The wing had to be pushed upwards, backwards and then downwards to get them into place. Two retaining arms were recessed into the rear fuselage (just above the Royal Navy stamp) which would be swing out to lock the wingtips into place.

Range:

The Firefly F1’s internal fuel load was a 145 Imp.gal tank fitted between the two cockpits. Two more tanks, of 23 Imp.gal each, were fitted flush to the leading edge of the wing centre sections. However, to maintain the Firefly’s centre of gravity, the main tank was limited to 116 Imp.gal when the wing tanks were empty.

Plumbing was fitted inside the wings to draw from two 45 Imp.gal or 90 Imp.gal long-rang tanks when fitted to the underwing attachment points.

On internal fuel only, the Firefly had a range of about 775 miles at a cruise speed of 233mph. With two 45 Imp.gal tanks, it could span 1088 miles at 207mph. With two 90 Imp.gal tanks it produced 1364 miles at 204mph.

Performance:

The F1 mounted a single 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce Griffon IIB engine rated at 1745hp at sea level or 1495hp at 14,000 ft. This drove a three-blade variable-pitch propeller with constant-speed control. It was designed specifically to give its peak output at low levels.

The Griffon was mounted in a modular ‘power-egg’ configuration, allowing it to be quickly detached and from the airframe and replaced.

After the 470th Firefly, the Griffon XII engine was mounted. While with essentially the same power output as the IIB, it had a more powerful supercharger and strengthened gearing.

Speed

In a clean configuration, the Firefly was rated as achieving 284mph at sea level, 273mph at 3500ft, and 319mph at 17,000ft. Climb rate was to 5000ft was 2.5 minutes and 5.75 min to 10,000ft

Burdened by two 90 Imp.gal tanks, the Griffon could pull the aircraft along at 257mph at sea level, 266mh at 3500ft and 288mph at 17,000ft

The Firefly reportedly became very tail-heavy as speed built up in a dive, as well as yaw to port.

The stall speed was about 85-90 knots (167km/h), with the Griffon easily able to haul the plane up again in the case of a carrier landing go-around.

FIREFLY FR1 & NF1

“In the summer of 1944 the RN was close to forming a night fighter squadron to be carrier based and equipped with a mixture of aircraft; the Fairey Firefly, a two-seater and the Grumman Hellcat or S6F, single-seater fighters both equipped with an American radar ASH. It was very satisfying having a good pilot or observer operator radar set, which had good performance and was simple to use. The US marines preferred to use theirs in single seaters, pilot operated. The Brits of course stuck to their observer-operated system for some years to come!”

Like its predecessor, the Fulmar, the Firefly was intended for fleet reconnaissance and hoped to have potential as a night fighter. The availability of an Observer to control and interpret an on-board radar system was considered as offering a major advantage over single-seat aircraft – both in shadowing surface ships and tracking aircraft.

As a result, a radar-carrying version of the Firefly was initiated at the same time as the F1 strike fighter. Its ASH (air-to-surface homing) radar was fitted on the production lines. But some Firefly F1s were retrofitted by FAA field maintenance units. These were designated F1As.

What made the FR1 and NF1 different from the F1 was a chin mount for a jettisonable bomb-shaped radar pod.

Several FR1s were fitted with the US supplied ASH (AN/APS-4) X-band radar module with its readouts installed in the rear cockpit. The conversion proved successful, so some 140 Firefly NF1s followed them off the production lines.

The APS-6 radar was considered a better night-fighter set. But this was not made available as the US Navy wanted all they could lay their hands on for their own night fighting units.

The APS4, however, was a surface-search radar with a secondary air-to-air capability. It was capable of detecting a bomber at some 6 nautical miles. It was also being fitted to US night intruders, including the Corsair.

In most other ways, the FR1 and NF1 was the same as the F1. However, the pilot was given an even higher seat, canopy and deeper windshield. The radome was fitted to an outrigger beneath the forward fuselage, and operational and display gear to the rear cockpit. The NF1 was given engine exhaust baffles.

The FR1 entered operation in October 1944. In December a flight was diverted to Norfolk in an effort to counter V1 ‘buzzbomb’ carrying He-111s flying within range of the home islands over the North Sea at night. Poor weather and wayward ground radar directions foiled their efforts, with only one contact – detected by the onboard radar in heavy cloud – eventually being fired upon.

A Firefly FR1 has its wings folded aboard an escort carrier.

An NF2 variant, which was to have radomes mounted on the wing’s leading edge, was not a success. The radome on one side and a bulging tank mirroring it on the other – as well as all the viewing equipment in the back seat - upset the aerodynamics and stability. It did not enter full production, and most of the 37 assembled were retrofitted to FR1 status.

The NF1, however, had difficulty taking off from light fleet carriers with less than 25kts of wind over the deck. As a result, Rocket Assisted Take-Off (RATO) kits were issued for the type.

Experience in the Observer-Pilot radar plot coordination convinced the RAF and RN of the value of the dual-seat setup. This led to the development of future two-seat aircraft types such as the Sea Vixen and Buccaneer, and a preference for weapons officers in future strike aircraft.

“The Firefly was a useful escort fighter because of its long range, heavy armament, and good maneuverability. Lack of defensive armament counted against it, but versatility in the ground- attack mode was to prove a strong asset. As a shipborne airplane it had pleasant handling characteristics for deck landing.

”