“Mussolini has become boastful; he has got into the habit of referring to the Mediterranean as ‘Mare Nostrum’, which means ‘our sea’. We are going to change all that ... we are going to change it to ‘Cunningham’s Pond’. I tell you that with no uncertain voice...”

“The plan for this attack had been in existence since 1935, when Italy invaded Abyssinia. The British C-in-C was then Admiral Sir William Wordsworth Fisher, a fearsome man, whom I had met when I was a Midshipman RNR. When Italian bombs were rained on the heads of the defenceless Abyssinians, very naturally he assumed that Britain would declare war at once.”

ORIGINS

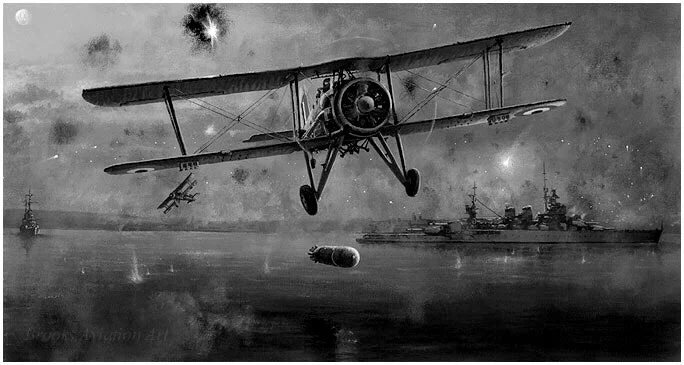

The idea of a surprise torpedo aircraft raid against a harbour was not a new one. A planned RN seaplane torpedo attack against the German naval base at Wilhelmshaven failed to eventuate before the end of World War I.

USS Saratoga and Lexington off Diamond Head, 1932.

The United States navy had already experienced surprise carrier attacks on Pearl Harbor - as part of the Fleet Problem 13 exercises in 1932, and again in 1938.

Rear Admiral Yarnell was in charge of the 'aggressor' force - including the 'scout' carriers Saratoga and Lexington, battleships and escorts. It was assumed he would attack with his battleships. But he left them behind. At dawn on Sunday February 7, 1932, a force of some 152 aircraft was launched against the harbour from the north-east, first attacking the army airfields before targeting battleship row. War-game umpires declared the attack a total surprise, and total success. Lexington and Saratoga repeated the achievement in similar games during 1938 - following up with a successful surprise strike against the naval facilities in San Francisco.

The Royal Navy kept the idea of harbour strikes alive in the late 20s and early 30s. However, it first started seriously thinking about attacking the Italian naval base of Taranto as as early as 1935.

Admiral William Wordsworth Fisher, then commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, feared he may soon be in a war with Italy after Mussolini ordered the invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia). The Royal Navy was making its presence felt under the auspices of the League of Nations. The rhetoric was heated.

Fisher summoned his commander of carriers – Rear Admiral Alexander Ramsay – and ordered a detailed breakdown of what it would take to strike a crippling blow against the Italian fleet.

The job of refining the detail of a raid on Taranto was given to the senior air crew aboard HMS Glorious. But the British government and League of Nations ultimately failed to intervene. The embryonic plan was sealed and shelved.

Another international crisis erupted just three years later. Germany annexed Austria. The emergence of the Axis coalition between Hitler and Mussolini appeared to make war in Europe almost inevitable.

Admiral Dudley Pound, who had replaced Fisher as commander of the Mediterranean fleet, decided it was time to revisit the idea of a crippling, pre-emptive blow against the Italian fleet.

Pound was so convinced of the imminence of war that he ordered his fleet out of its anchorage in Malta to the more distant facility at Alexandria, Egypt.

HMS Glorious’ Captain, Lumley St George Lyster, was summoned aboard the flagship HMS Queen Elizabeth to pour over the old Abyssinian Crisis notes. His job was to draw up a new plan accommodating fresh developments in both Italian and British defences and technologies.

Lyster, with the assistance of Commander (Flying) Guy Willoughby and Senior Observer Commander Lachlan Mackintosh, put HMS Glorious’ air group through an intense period of tests and training all designed to evaluate the chances of successfully striking the Taranto facility.

The outline of a plausible plan soon emerged: The attack would have to take place at night (for which HMS Glorious’ air group had been in training). A bomb attack on the shore installations would act as a diversion as the main attack – by torpedo – developed. All would be illuminated by air-dropped flares.

HMS Glorious’ air command staff calculated a casualty rate of roughly 10 per cent.

Admiral Pound, however, was not convinced. He believed losses to both aircraft and aircrew would be much higher. The risk to his ships, he thought, was also prohibitive. As a result he deemed such a raid to be a contingency instead of an active plan. He did not relay the idea to his Admiralty superiors.

As tensions diminished once again, interest in the raid diminished.

For a second time, the idea was shelved.

But Glorious’ Mediterranean foray would have lasting influence on the FAA: Those who served in her pre-war would win a total of 5 DSOs and 28 DSCs.

PRELUDE

“I am afraid you are terribly short of “air”, but there again I do not see what can be done because, as you will realize, every available aircraft is wanted in home waters. The one lesson we have learnt here is that it is essential to have fighter protection over the fleet whenever they are within the range of enemy bombers. You will be without such protection, which is a very serious matter, but I do not see any way of rectifying it.”

When Italy declared war on June 10, 1940, the Royal Navy was operating only a reduced squadron of cruisers and the old carrier HMS Eagle in the Mediterranean.

After all, the Mediterranean was France’s responsibility and Britain’s fleet had been fighting to maintain control over the North Sea and interdict Germany’s invasion of Norway.

Mediterranean stalwart HMS Glorious had been sent to reinforce the Home Fleet in April 1940. Soon she would fall to the guns of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau – without a single aircraft in the air.

France’s capitulation in May 1940 was a catastrophic blow.

But Admiral Cunningham – who had stepped into the shoes of commander of the Mediterranean fleet in 1939 - strove to maintain the initiative. Cunningham boldly deployed what ships he had to the central Mediterranean as both provocation and protection.

He had little choice.

Britain was in a bind: The Royal Navy now had to run convoys from Gibraltar to Malta, and again from Malta to Alexandria. This meant running a gauntlet including airbases in Sardinia and Sicily, the narrow waters around Pantelleria Island, and more airbases on the south of the Italian peninsulas well as along the north coast of Africa.

The Italians were running their own heavily protected convoys – inevitably crossing the path of the British as they ploughed the waters between Italy and Libya.

Looming large over this strategic nautical crossroads were the major naval bases of Valletta, and Taranto.

The first clash came on July 9, merely a month after Italy declared war. HMS Warspite hit the battleship Giulio Cesare with a 15-inch shell at extreme range during the Battle of Calabria. HMS Eagle – operating just 18 Swordfish and three Sea Gladiators – launched several torpedo attacks against Italy’s capital ships, but none struck home.

Italy’s retaliation by air proved to be a revelation: More than 400 bombs were dropped on the British fleet.

Cunningham wrote after the war:

It is not too much to say of those early months that the Italians’ high-level bombing was the best I have ever seen, far better than the German’s

But, from this point, the Italian fleet demonstrated a growing reluctance to engage in a fight – despite Cunningham ‘trailing his coat-tails’ (making aggressive sorties) some 16 times during the following months.

Cunningham’s plight, however, was somewhat relieved in August 1940. Reinforcements finally arrived.

The heavily modernised battleship HMS Valiant brought with her a modern suite of radar and anti-aircraft guns. So too did the two light anti-aircraft cruisers in her company.

But most significant was the arrival of the freshly commissioned HMS Illustrious.

Cunningham already had a plan.

Pound had told Cunningham of the idea to raid Taranto when handing over command. But key personnel – including HMS Glorious’ Captain Lyster – had long since moved on.

Ark Royal, however, had provided a tantalising taste of what was possible: Six of her Swordfish successfully swooped on the French battlecruiser Dunkerque in Oran harbour. Passing over the breakwater from out of the sun, four torpedoes – all dropped in the shallows – had found their mark.

And now the Taranto raid’s chief architect, Captain Lyster, was back as Rear Admiral (Carriers), aboard HMS Illustrious.

ENTER ILLUSTRIOUS

The name-ship of a new class – and a new concept – of aircraft carrier, HMS Illustrious had been launched in 1939 and completed in May 1940. Like most RN carriers, she immediately set sail for Bermuda to conduct an intensive working-up program for both ship and aircrew.

It was during these exercises that the more experienced Fleet Air Arm pilots determined to find ways to enhance the survivability of their lumbering Swordfish. The pilots discovered the slow but nimble biplane could quickly be stalled – virtually hanging in the air by its propeller at low level before flicking off to one side – causing the attacking aircraft to overshoot and become disoriented.

During one such fighter evasion exercise the ‘enemy’ aircraft – an FAA machine - became disoriented and crashed into the sea. It was a tactic to be reproduced effectively several times in the heat of real combat.

Illustrious would return to her home port on July 26.

Fully fuelled, stocked and nesting a full complement of aircraft, HMS Illustrious would receive Admiral Lyster aboard on the 19th of August. On August 22, HMS illustrious headed down the river Clyde and set course for Gibraltar.

On August 30 she joined Force F, along with Valiant and the old cruisers Calcutta and Coventry,. They would sortie with Force H – the carrier Ark Royal, the battlecruiser Renown, the cruiser Sheffield and 12 destroyers – along with a convoy of three merchant ships to Malta.

As Illustrious slipped past the Pantelleria narrows and cruised by Malta on September 2 she would deliver six Swordfish, and a large stock of spare parts, to the FAA unit based there.

Illustrious had barely finished tying up in Alexandria before Admiral Lyster and Captain Boyd were summoned aboard Cunningham’s flagship. At the top of the agenda was the ‘best way to annoy the Italians’.

Naturally, the idea of attacking the battleships in Taranto harbour rose to the fore.

Admiral Lyster and Captain Boyd were faced with a formidable challenge. The raid could no longer be a pre-emptive surprise attack, as originally intended. Instead, the RN’s carrier aircraft would be launched against a naval facility already on a full war footing.

Air crews, while well trained, would need considerable real war experience before attempting such a daring feat. So a gruelling series of raids were planned in conjunction with escort operations in the lead up to the portentous attack date Cunningham had set – October 21, Trafalgar Day.

AN AMERICAN EXCEPTION

Aboard HMS Illustrious was Lieutenant Commander John N. Opie III, USN. After just three days training for his new role of naval observer, Opie soon found himself bundled across the Atlantic and dumped in harm’s way aboard a variety of active British warships.

He wasn’t really supposed to be there. His mere presence was a direct violation of neutrality.

But the USN was adamant that any and all intelligence he could provide on how modern equipment and doctrine was performing in actual warfare – instead of in theory – would prove invaluable.

As a result, Opie would end up submitting dozens of reports detailing his direct observations as well as arranging for the forwarding of many of the RN’s own Top Secret internal reports and reviews.

Taranto would be among his most significant experiences.

THE PLAN

“The attack had been given the code name ‘Operation Judgement’, and we all hoped that it was the Italians who were about to meet their Maker and not us”

As the RN practiced and established its naval aviation doctrine during the 1930s – largely aboard HMS Glorious – it had ruled out the notion of dawn and dusk torpedo attacks.

The idea sounded nominal: Enemy ships would be silhouetted against the sunrise or sunset while the attacking aircraft would be lost against the gloom of the dark sky.

But, at least in the Mediterranean, the Sun would rise and set very quickly. Timing the attack therefore needed to be impractically precise.

Therefore the RN began practicing night carrier-launched air attacks – the only nation to do so.

In 1940, the Italians already feared air-strikes from the RN carriers. Harassment raids had been ongoing from day one. A Mediterranean-spanning network of informants, surveillance aircraft and submarines was quickly geared to keeping the Regia Marina informed as to the whereabouts of these deadly ships.

So great care would need to be taken in concealing the RN’s intentions.

Cunningham devised a cunning deception, which also served to further Britain’s growing needs in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Two carriers, five battleships, nine cruisers, 27 destroyers and 11 merchant ships put to sea at the same time. These were divided into five task forces and three convoys – each with different objectives and destinations.

ALLIED ORDER OF BATTLE

SWORDFISH TSR (Torpedo, Spotter, Reconnaissance)

“My Stringbag flies over the ocean,

My Stringbag flies over the sea.

If it weren’t for King George’s Swordfish,

Where the hell would the Royal Navy be?

”

Nobody ever called the Fairy torpedo bomber by its designation, TSR 2. Even Swordfish was rarely used. Instead, a nickname made in jest by someone commenting on its ability to carry a startling array of weapons had stuck – permanently:

“No housewife on a shopping spree could have crammed more into her string bag,”

Stringbag it would remain. No doubt assisted by the radial-engined aircraft’s ungainly array of struts, wires and fabric-covered tubing.

The name also exposes an error in many modern accounts of the aircraft. It was not a design anachronism. It represented the pinnacle of proven, applied practical technology. As such, it was immensely flexible, durable and reliable.

Despite common assertions to the contrary, the Swordfish was also designed to be a dive bomber. It had been a Greek Government's requirements during the aircraft's development, stipulated before it lost interest. Nevertheless, the wire and steel-tube frame had been stressed to accommodate this.

The Swordfish could be stood on its nose, its fixed undercarriage, struts and dual mainplanes keeping it slow enough and controllable enough to deliver its weapons accurately.

What was lacking was the conviction in the RAF, and therefore the RN’s inter-war air arm, that this was the most effective means of delivering a bomb. As a result, training and practice in the technique was scarce.

The Swordfish’s greatest weakness, however, was its speed. Official performance testing figures give the biplane a top speed of 143mph while burdened with its 18inch, 1550lb MkXII torpedo. Aircrew, however, repeatedly report Stringbags encumbered with a torpedo and long-range fuel tanks maxed-out at just 93 knots.

In windy conditions, this made even chasing a battleship a laborious task.

Key to its survivability – along with the new stall tactics being developed by Illustrious’ pilots – was its impressive low-level, low-speed manoeuvrability. At wave-top heights, a jinking Swordfish could prove incredibly hard to hit.

At Taranto, the Swordfish's strength lay in its ability to be thrown about at night in extreme manoeuvres while in confined spaces - and at zero feet.

“Apparently, when a US naval aviator first saw the strange-looking biplane, he asked a British officer where the aircraft had come from. ‘Fairey’s’ was the reply. ‘That figures’ responded the American.”

SHALLOW-WATER TORPEDOES

“... the Italians had a shock to come, because our aerial torpedoes were fitted with Duplex Pistols, a magnetic device which exploded the torpedo’s warhead when it passed underneath the ship... These attachments had been invented at HMS Vernon when Captain Boyd had been in command.”

The shallow waters of the Taranto anchorage posed a challenge for air-dropped torpedoes. These had tendency to dive deep before the guidance mechanism kicked in and brought them up to a pre-set depth.

But a solution had been found.

The Fleet Air Arm did not use timber attachments to their torpedoes in the same manner as the Japanese at Pearl Harbor, as many accounts report. (It was the Italians that developed this technique for dropping torpedoes from their SM79 trimotors. This was passed on to Japanese delegations in 1940/41).

Instead, each 18-inch Mk XII torpedo was linked to its Swordfish by a strand of wire. This would hold the nose of the torpedo up as it fell to the water, producing a belly-flop instead of a dive. This enabled them to be dropped in water as shallow as 22 feet.

At Taranto the torpedoes were set to run at 27 knots at a pre-set depth of 33 feet. This was calculated to enable the torpedoes to pass under anti-torpedo netting while still allowing the new Duplex magnetic warheads to ‘sense’ a warship above and explode while passing beneath, or detonate on contact. Taranto's battleship harbour had an average depth of 49 feet.

LONG RANGE FUEL TANKS

“One’s back and head rested on it (the fuel tank) and it was the explosion of one of these that had set off the hangar fire three weeks earlier. The tank was hardly a morale-booster to have with you when going in to face intensive anti-aircraft fire.”

While the Swordfish had an excellent naval endurance, handy for loitering on anti-submarine patrols, it had a poor cruising speed. This amounted to a reasonably short radius of action.

To keep Illustrious safe, the torpedo and dive bombers would have to carry external fuel tanks.

In the case of the torpedo bomber, this had to be in the cockpit: the usual spot, slung between the wheels, was occupied by the torpedo.

As a result, a 60 gallon tank was secured to the Observer's booth behind the pilot by metal straps. The Observer, and his plot-board, now had to take the smaller seat previously occupied by the air gunner.

In the case of the dive-bombing Swordfish, a more traditional tank would be strapped under the fuselage. Their six bombs were attached to the wings, three on each side.

RADAR FIGHTER DIRECTION

Operators with early examples of radar sets aboard an RN warship.

The Royal Navy was now engaging in an entirely new form of warfare: radar direction. Experimentation by Ark Royal in combining radar plots of approaching enemy aircraft with navigational calculations - and then transmitting an intercept course to a standing fighter patrol - had proven inordinately successful.

As a result HMS Illustrious had had her completion date delayed by up to three months in order for new masts to be installed, air warning radars fitted – and space found for rudimentary fighter direction facilities.

It would immediately pay off.

Wherever Illustrious went, her combination of radar, directors and fighters brought with her local air superiority.

Reconnaissance aircraft were now regularly being knocked out of the sky before they could make their reports. Those that survived were often too busy taking evasive action to gather a comprehensive report on the number and types of ships in formation.

Incoming raids were sustaining serious losses, as well as having their bombing runs disrupted.

But such a directed CAP posed an even more fundamental problem. Attacking aircraft often had to be very careful of their fuel management because of the extreme ranges involved. Evading interceptors – either by attempting to out-flank their movements or by hiding in cloud – took extra speed and time.

The CAP fighters had their mobile airfield beneath them, so fuel management played much less on their minds.

In 1940, such fighter coordination at sea was entirely new and unique to the Royal Navy.

Commander Opie, USN, took careful note.

“At the final briefing in the wardroom a lage-scale map of Taranto and a magnificent collection of enlarged prints of the photographs I had brought back from Malta were pinned to clipboard backings and were on display. It was possible to study every aspect of the harbour and its defences, and the balloon; and, of course, all the ships in detail.”

MALTA RECONNAISSANCE

Central to Operation Judgement’s success was the possession of detailed intelligence as to the composition and location of Taranto’s defences.

The Short Sunderland flying boats based in Malta were inadequate: they were simply too slow and flew too low to survive flying over such a heavily protected shore facility.

But, in September 1940, three RAF Martin Marylands of 431 General Reconnaissance Flight arrived. These were capable of 278mph with a ceiling greater than 28,000ft. This put them out of reach of any fighter the Italians then possessed.

Soon Rear Admiral Lyster’s intelligence team picked out the shapes of gun emplacements, searchlights and anti-torpedo nets around the harbour. Strange blobs were eventually realised to be moored barrage balloons.

This was a serious obstacle: at night, the cables slung beneath them would be invisible.

THE BATTLE FLEET

FORCE A:

Carrier squadron:

HMS Illustrious (Flag Rear Admiral Lyster)

806 Squadron: 15 Fulmar MkI

815 Squadron: 9 Swordfish

819 Squadron: 9 Swordfish

813 Squadron*: 4 Swordfish, 2 Sea Gladiator

824 Squadron*: 2 Swordfish

* Detached from HMS Eagle

HMS Eagle*: 824 Squadron, 17 Swordfish; 3 Sea Gladiator

813 Squadron: 9 Swordfish

824 Squadron: 9 Swordfish

813 Fighter Flight: 4 Sea Gladiator

* Aircraft from 813 Squadron & Fighter Flight, 824 Squadron not yet detached to Illustrious.

Battle squadron:

HMS Warspite (Flag Admiral Cunningham), Valiant, Malaya, Ramillies

Destroyer squadron:

HMS Decoy, Defender, Hasty, Havoc, Hereward, Hero, Hyperion, Ilex, Janis, Jervis, Juno and Mohawk.

FORCE B:

HMAS Sydney, HMS Ajax, 2x destroyers

FORCE C:

HMS Orion (Flag Rear Admiral Pridham-Wippell)

FORCE F:

HMS Barham, Berwick, Glasgow, with the destroyers HMS Greyhound, Gallant, Griffin (supplemented by Faulknor, Fortune and Fury upon detachment from Force H)

FORCE H

HMS Ark Royal (Flag Vice-Admiral Somerville)

HMS Sheffield, 8x destroyers

CONVOY AN-6

HMS Calcutta, Coventry, destroyers HMS Dainty, HMAS Vampire, Waterhen, Voyager, 3x slow freighters.

CONVOY MW-3

HMS York, Gloucester, Coventry, 3x destroyers, 7x merchants

STRIKE FORCE (Taranto detachment)

HMS Illustrious

HMS York, Berwick, Glasgow, Glouchester and the destroyers Hasty, Havock, Hyperion and Ilex

FORCE X (detachment)

HMAS Sydney, Orion, Ajax with destroyers Mohawk and Nubian.

ITALIAN ORDER OF BATTLE

Cruisers and destroyers arrayed in Taranto's Mare Piccolo in the 1930s

TARANTO

“The Italians possessed all the necessary skills to make it into the impregnable fortress that it should have been: the guns, placed at strategic points on all the breakwaters, and all over the harbour, were expected to safeguard all the ancillary installations ashore which combined to make this their most important port. It had to be impregnable for a huge fleet to be able to rest, and to carry out repairs in complete security.”

Italy’s air force was adamant it could constantly surveil all approaches to mainland facilities. This would provide ample time for warships to mobilise and bombers to scramble.

But, at Taranto, an alternative form of early warning was offered by 13 sound-detection devices placed at strategic points around the harbour. These were capable of “hearing” aircraft out to 25 nautical miles (29 miles or 46km). It was sufficient notice to bring to alert the searchlight and gun crews, though not enough for an effective air-defence scramble.

Then there were the 22 searchlights strung out around both harbours in the hope of catching attacking ships and aircraft in their beams to provide easier sighting for the array of defending guns.

Defending the base was 21 gun batteries of dual-purpose – though World War I vintage - 4in guns. On the shore were 13 mounts, while the remaining eight were installed on immobile barges anchored along the boundary of the Mar Grande.

Close-range protection was offered 84 20mm Breda anti-aircraft guns and 109 13.2mm Breda machine guns. These were in a mix of single and twin mounts.

Finally, there were the guns and searchlights aboard the warships themselves. The base commander had stipulated that ships were limited to using only their armament while under direct attack. The order's read:

‘No barrage fire at the same time as that of shore batteries. Machine guns to be manned and fired with the main armament against aircraft visible to the naked eye or illuminated by searchlight.’

The ships maintained a high ready of alertness while in harbour. Standing orders stipulated that half the anti-aircraft armament be manned at all times, rising to full AA manning and half main armament manning at night and dawn.

“At Supermarina it was taken for granted that if British forces should come within 180 miles operating range of their torpedo planes from Taranto, the Italian forces would sortie to engage the British and prevent them launching an air attack on the harbour”

Battleships are seen anchored in Mar Grande in this Maryland reconnaissance photo taken in the lead-up to Operation Judgement.

Mar Grande (Outer Harbour)

The main warship anchorage was in the deeper waters on the eastern side of the Mar Grande close to the major harbour facilities there – including the oil depot, dry dock and floating dock.

A large curved mole named the Diga di Tarantola provided shelter for the large anchorage’s waters. A second mole, the Diga di San Vito combined with a set of submerged breakwaters linking the islets of Isoletto San Paolo and San Pietro in a huge arc to the mainland.

San Pietro was also the site of an acoustic hydrophone station, listening for the approach of submarines or – at night – warships.

While the moles, breakwaters and islands formed a passive barrier to the open sea, a string of 90 barrage balloons were deployed about the battleship anchorage as a deadly obstacle for aircraft. Moorings ran along the eastern edge of the Mar Grande and along the Diga di Tarantola, while rafts attached to the western torpedo net tethered several more. But a storm early in November had ripped many of these balloons from their tethers – leaving just 27 in the air when the British attacked.

The final line of passive defence was a network of torpedo netting intended to shield the valuable battleships as they sat at anchor. It had been calculated some 12.6km of netting was required to fully encompass the warships. Only 4.2km was actively deployed at the time of the raid – with a further 2.9km coiled up ashore awaiting repairs after the same storm that had damaged so many of the defensive balloons.

Within this whole interlaced embrace were the battleship moorings, though some cruisers and destroyers would often be moored about the outer edges.

The line of destroyers and cruisers arrayed along the quay in Mar Piccolo, as captured by a Maryland reconnaissance flight shortly before Operation Judgement.

Mar Piccolo (Inner Harbour)

The main naval shore facility was on the east side of the canal, on the southern edge of Mar Piccolo. The long wharf with its chain of jetties offered a sheltered anchorage for the fleet’s lighter vessels – including cruisers.

On its shore was also a seaplane ramp, with affiliated storage sheds, hangars and administration buildings.

Along with the major warships in the inner harbour were five torpedo boats, 16 submarines, four minesweepers and one minelayer. Auxiliaries included nine tankers, supply ships and hospital ships along with an assortment of civilian tugs and merchant ships.

Regia Marina

1ST BATTLESHIP SQUADRON

5th Division

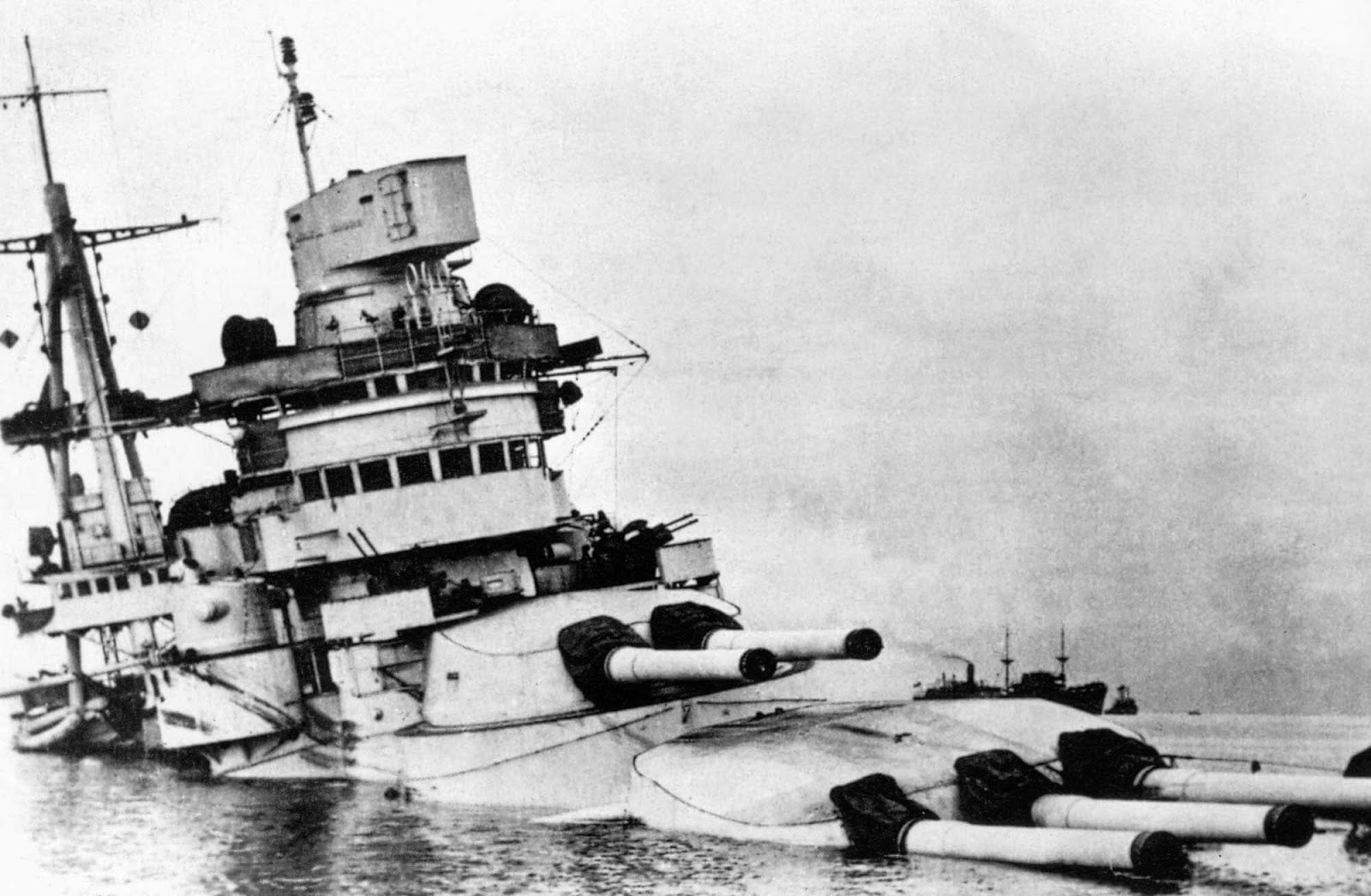

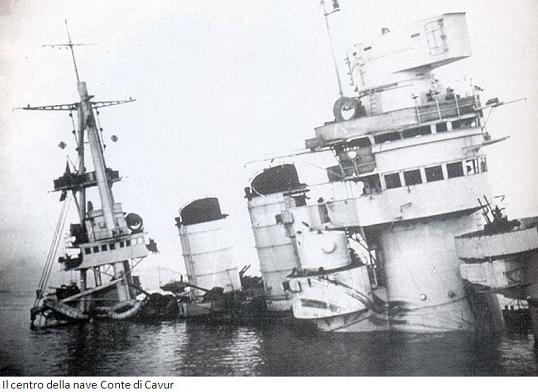

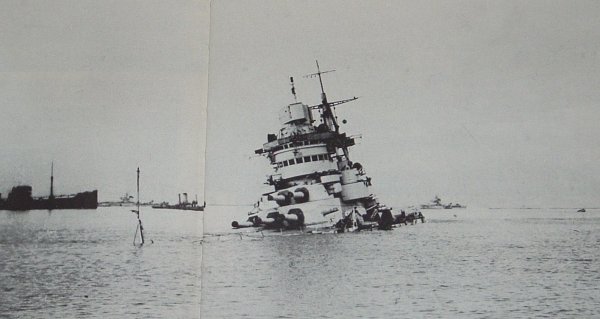

Conti di Cavour, Giulio Cesare, Andrea Doria

9th Division

Littorio, Vittorio Veneto, Caio Duilio

2nd CRUISER SQUADRON

1st Division

Pola, Zara, Goriza, Fiume

3rd Division

Trento, Trieste, Bolzano

8th Division

Duca degli Abruzzi, Giuseppe Garibaldi

Seaplane carrier: Giuseppe Mariglia

4th DESTROYER FLOTILLA

Alfredo Oriani, Giosui Carducci, Vincenzo Gioberti, Vittorio Alfieri, Libeccio, Baleno, Lampo, Folgore

HMS ILLUSTRIOUS landing Swordfish in June 1940. Picture: Fleet Air Arm Museum CARS 1/171

OPERATION MIKE BRAVO ATE (MB8)

“Apart from excellent results obtained in offensive action, perhaps the most surprising feature of the whole operation was the almost clockwork regularity with which the convoys ran, ships unloaded guns and material, and with which the rendezvous of widely dispersed units were reached at the appointed time.”

Just days before the scheduled attack, a serious incident threatened the viability of the whole operation.

At 11am on Friday October 18, an accidental fire erupted in HMS Illustrious’ forward hangar.

There were 30 aircraft tightly packed into the confined space as maintenance crews raced to get all in pristine condition before the raid scheduled for just two days time. This involved fitting large auxiliary fuel tanks in the Swordfish cockpits.

Amid the hustle and bustle, a mechanic slipped. Falling, he also dropped a tool – which sparked. This ignited fumes from the long-range tanks, causing a small explosion. This tore apart the Swordfish he was working on and the flames quickly spread to adjoining aircraft.

The carrier was instantly called to General Fire Stations. The internal ventilation systems were shut down and the fire curtains dropped - confining the blaze to "A" hangar (the forward third of the hangar space).

Illustrious’ crew quickly activated the hangar’s network of fire-suppression sprayers in Hangar A to avert catastrophe. It worked. Just two aircraft would be judged destroyed and three badly damaged by the blaze.

One of Illustrious' squadron duty officers recalled:

... The drainage scuppers at each side of the after entrance lobby to the hangar pouring away a blazing mixture of sea water and petrol with flames four feet high being beaten down by the powerful sprays.

The ship's company was stood down from fire stations at 12:32 But the sprayers used salt water drawn direct from the sea. This meant the aircraft within the hangar had been doused with highly corrosive liquid.

An enormous clean-up and repair effort was required to get as many aircraft as possible back in the air. This involved stripping several planes and engines apart, washing components with fresh water, coating them with protective oil – and reassembling it all again.

Shortly after an order was issued aboard Illustrious that only rubber hammers be used when work was being done on an aircraft's fuel systems.

It was obvious Illustrious would not be ready in time for full moon of Nelson’s celebration.

At first, an alternate date of October 31 was considered. But it would be a dark, moonless night. This would place too great a reliance on flare droppers. The next available opportunity, with illumination from the moon, would be the night of November 11.

In one way the accidental fire had been fortuitous.

It allowed HMS Illustrious’ movements to be masked by an urgent rush of ships about the Eastern Mediterranean to counter Italy's October 28 invasion of Greece.

NOVEMBER 4:

Cunningham’s first piece on the chess-board of MB8 was Convoy AN6. Three slow merchant ships carrying petrol departed Port Said for Athens, escorted by the AA cruisers HMS Calcutta and Coventry and the destroyers HMS Dainty, HMAS Vampire, Waterhen and Voyager. Their course would take them around the east end of Crete, though they would be within the range of Italian reconnaissance and bombers from Leros and Rhodes for the entire journey.

NOVEMBER 5:

Convoy MW3 sailed from Alexandria, headed for Malta and Crete. This convoy was built around five freighters destined for Valetta and a further three headed to Suda Bay. Escorting them would be the cruisers HMS Ajax and HMAS Sydney. The intention was for MW3 to rendezvous with AN6 on November 6 when some 200 miles north of Alexandria to combine the firepower of their escorts.

NOVEMBER 6:

Cunningham now deployed Force A from Alexandria. In formation were HMS Warspite, Valiant, Malaya and Ramillies in company with the cruisers HMS Gloucester, York and Orion. Screening them were the destroyers HMS Nubian, Mohawk, Jervis, Janis, Juno, Hyperion, Hasty, Hero, Hereward, Havoc, Ilex, Decoy and Defender.

HMS Illustrious was with them, alone. HMS Eagle had not been able to overcome a series of defects that had slowly become apparent after anear-misses during the Battle of Calabria. Among them was contamination of her aviation petrol supply by salt water. Most serious, however, were leaks in the petrol distribution network of pipes which threatened a catastrophic explosion.

Lyster's hopes of launching a 30-strong Swordfish strike were dashed.

But Eagle would not go unrepresented.

Six Swordfish and eight crew were transferred to Illustrious to bring her air group back up to maximum strength. Two of Eagle’s requisitioned Sea Gladiators would also take station as a deck park aboard Illustrious to supplement the fighter defence.

Cunningham set Force A on a north-westerly course at 20 knots. His intention was to catch up with the Malta-bound elements of the earlier convoys on November 8.

Fulmars of 806 Squadron and a Swordfish ranged on HMS Illustrious in November 1940. Note the two Sea Gladiators of 813 Fighter Flight tucked away aft of the island. They were transferred from HMS Eagle for the Taranto strike to increase the number of fighters on board.

NOVEMBER 7:

By now the Italians sensed something was brewing. Reports were streaming in of widely separated – but big - RN formations converging from at least three different directions.

HMS Ark Royal, with the cruiser HMS Sheffield and destroyers Faulkner, Duncan, Firedrake, Forester, Fortune and Fury had departed Gibraltar as Force H and was making its way northeast towards Sardinia.

Force F moved out with them – though it was intended these ships would break through the 90-mile gap between Sicily and Tunisia to join up with Cunningham’s Eastern Mediterranean fleet. Force F comprised the battleship HMS Barham and the destroyers HMS Encounter, Gallant, Greyhound and Griffin. The cruisers HMS Berwick and Glasgow were part of this force, though they - along with Barham - had the added role of ferrying fresh troops to Malta as part of their passage.

The escorts of AN6 and MW3 (Forces B and C) met their rendezvous off Crete to form Force X. With them between Crete and Greece was convoy MW3. Their mutual ultimate destination was the waters off Malta. AN6 was scheduled to arrive at Athen’s port of Pireus before dawn the next day.

Meanwhile, Cunningham’s Force A was continuing on its north-westerly course in waters north of Benghazi.

HMS Illustrious picked up a shadowing Italian aircraft at a range of 25 miles. No radio transmission was detected. No fighter interception was made.

NOVEMBER 8

The Supermarina’s command staff was by now seriously concerned. So, at dawn, an intensive reconnaissance effort was launched from Sardinia in the west and Leros and Rhodes in the east. Aircraft from Sicily protectively scoured the waters between the home peninsula and Libya.

All were tasked with locating and tracking the British fleets.

Cunningham’s Force A had taken up station some 200 miles east of Malta to help screen the movements of Convoy MW3.

At 12:30 Illustrious’ radar operators again reported ‘bogeys’ (unidentified contacts) appearing on their screens at a range of 20 miles. It was an Italian flight of Cant 501 Seagull and 506 Heron seaplanes, scouring the sea from a height of 6000ft.

A poor quality but significant photograph as it shows two Sea Gladiators, bottom left, on outriggers while aboard HMS Illustrious during Operation Judgement. A Fulmar is about to touch-down.

Two of Eagle's Sea Gladiators were contributing to Illustrious' standing air patrol. These intercepted and shot down the Cant Z-501 of 186 Squadriglia. Three of its crew were plucked from rough seas by a British Sunderland flying boat.

The approaching Italian aircraft attempted to force their way past the fighters, but all were turned back before they could directly observe the fleet.

An hour later, a similar scenario unfolded near Force H as it passed Algiers: Ark Royal’s fighter direction officers alerted her Fulmars to the arrival of an Italian reconnaissance aircraft which they managed to turn away.

Illustrious would again detect a scout, this time at a distance of 25 miles, about 14:00. Her Fulmars failed to find the Italian.

While nether force had been carefully observed, the Italians nevertheless now knew roughly where the fleet elements were.

At 16:30, Illustrious’ radar screens lit up again. The fleet had 20 minutes in which to respond. Illustrious’ standing air patrol of two Fulmars was vectored to intercept, and a ‘ready’ aircraft on deck scrambled.

The contacts were calculated to be at a height of 12,000 feet. This time it was two formations of SM79s from 34 Stormo totalling 15 aircraft, loaded with bombs for a high-level attack. Two Fulmars of 806 squadron were soon among one of the formations (with seven aircraft) while still 30 miles out from the fleet. One SM79 was claimed shot down and the others were forced to jettison their bombs in their efforts to evade. None made it over the fleet.

Another flight of three bombers was detected at 17:00: Fulmars gave chase, but were unable to overhaul the retreating aircraft.

An hour later, HMS Ark Royal's radar operators detected another approaching aircraft. The official after-action report (ADM 199/798) report the shooting down of an S-79:

At 1800, 808 Squadron, Blue Section, was about to land and had lowered their hooks when an aircraft was sighted on the starboard beam and they were sent off after it, and shot it down. The combat report of the section leader is attached. The last aircraft were landed on at 1900.

As the Italians strove to probe the RN’s defences and intentions, Force H separated from Force F and headed towards the Italian islands of Sardinia for Operation Crack.

To the east, the cruisers of Force X would merge with Force A and together the warships covered Convoy MW3’s journey towards Malta.

An Italian Cant z506 reconnaissance seaplane.

NOVEMBER 9

By now the Supermarina had a pretty good idea what number – and type – of ships the RN had active.

There were far too many warships to simply be covering a handful of freighters as they moved westwards towards Malta.

So what was Cunningham up to?

Again, the order of the day was for as many reconnaissance aircraft to get into the air as soon as possible. Once positions were pinned down, follow-up high-level bomber strikes would be launched.

OPERATION COAT

Meanwhile, HMS Ark Royal was flying off its own dawn attack. Nine Swordfish from 810, 818 and 820 squadrons were sent to bomb the Italian Cagliari airbase in Operation Crack.

About the same time, three of 808 Squadron's Fulmars were sent into the air - destination Malta. Their orders were to refuel before flying on to reinforce HMS Illustrious' defences.

No Swordfish were lost in the raid, which did substantial damage to the airfield’s hangars and several of the reconnaissance aircraft there. A Cant 506b shadowed the Swordfish back to the fleet, but it was shot down by Ark Royal’s Fulmar CAP at 0950.

It was cause for retaliation.

OPERATION MB8

The persistence of the Italian reconnaissance wing was again evident. HMS Illustrious located a flight of three aircraft at 09:00, though these did not linger long enough for an interception.

At 11:00 a shadower was reported by both radar and radio operators: This time Force A’s position had been broadcast in an accurate and timely manner.

But Cunningham had just split his fleet into three new task groups.

HMS Ramillies and three destroyers would accompany MW3 into Valetta.

The cruisers HMS York, Gloucester, Calcutta and Coventry were to aggressively sweep north of Malta in search of Italian shipping.

The remainder of Force A – HMS Illustrious, three battleships and 14 destroyers – would continue northwest towards the Sicilian Narrows to meet Force F.

The Italians were overwhelmed by piecemeal and conflicting reports.

Another Italian aircraft attempted to shadow Force A at 16:00. Illustrious’ Fulmars were directed to a successful intercept, and the Cant Z-506 from 170 Squadriglia was shot down as it attempted to evade in cloud.

But HMS Illustrious was to mysteriously lose a Swordfish. The aircraft suffered engine failure shortly after take-off and was forced to ditch. The two crew members were quickly pulled from the water by HMS Nubian, but there was little indication as to what the problem had been.

Having sailed with just 24 Swordfish aboard, the loss of even one represented a not insignificant portion of the total available strike force.

Then, later that same afternoon, a second Swordfish crashed after engine failure.

OPERATION CRACK

After Force H re-joined Force F, some 25 to 30 Italian SM79 bombers from Sicily were detected approaching at 20,000 feet. This was well above the Fulmar’s effective ceiling. But the height was also too great for accurate bombing, so, as the bombers crossed over the fleet, they dropped to a height of 13,000ft – where the Fulmars and Skuas were waiting for them.

One Fulmar claimed a kill, confirmed by HMS Glasgow.

Nevertheless most of the bombers were able to make their attack runs - HMS Barham, Ark Royal and Duncan later reporting minor damage from near misses.

A flight of Italian SM79 Sparrowhawk bombers.

Vice-Admiral Somerville later said:

They came in one big wave – four sections of five bombers each. Our fighters engaged them as they came in but could not make any visible impression on them. A lot of the pilots were changed when Ark Royal was home, and the new lot are still pretty green. Our AA fire as they came over was damned bad, and I was very angry. Of course, this is just an odd collection of ships that have never worked together, so what can you expect.

His anger was not entirely warranted: Italian records show 18 aircraft returned severely damaged and with casualties.

Force H and Ark Royal turned back for Gibraltar late in the afternoon – but not before flying off three Fulmars to Malta. Force F also turned in an effort to deceive the Italians. At midnight, Force F switched course again and sprinted towards the channel leading through the Sicilian Narrows.

The Italians, however, had not been deceived.

That evening four destroyers and nine submarines were deployed in the Narrows to counter just such an attempted passage.

Fortunately for the RN, the radar-less Italian destroyers did not spot the darkened ships as they raced past. The submarines were caught out of position.

Observers on the island of Pantelleria, however, radioed a report of eastward-bound warships. But detail was lacking.

Report from Commanding Officer, HMS Ark Royal to Flag Officer Commanding, Force ‘H’

ADM 199/ 798 12 November 1940

Operation ‘Coat’ – attack on Cagliari, 9 November 1940

The attached reports on Operation ‘Coat’: are submitted in accordance with C.A.F.Os. 3572/ 39, 3373/ 39 and 1409/ 40.

2. – On 8th November, the Fulmars were just able to catch a Savoia 79, (after a long chase) which had been shadowing the Fleet. Skuas could not have overtaken the shadower. The section of Fulmars in the air was directed in the first place from the plot obtained from R.D/ F. bearings. The enemy aircraft was then sighted and the Fulmars were subsequently directed by R/ T based on sighting reports.

3. – The tactics employed by 808 Squadron and the formation beam attack has been discussed with the Squadron Commander. It is thought that Red section would have destroyed the Cant floatplane more quickly and with less expenditure of ammunition had they carried out their initial attack from astern. This type of floatplane has in the past, been shot down by Skuas attacking from astern and appears to break up when hit.

4. – The failure of the Fulmars to take a heavier toll of the bomber formation is attributable to shortage of ammunition as they had been already engaged with the Cant flying-boat, and to the adoption of the beam formation attack.

5. – At the time the hostile bombing formation came on the R D/ F screen there were two sections of fighters in the air and one standing by on deck. They all made contact and engaged the enemy. One section of Fulmars had taken departure for Malta and the other two sections of Fulmars had been in the air and were refuelling.

6. The remarks of the Commanding Officer 800 Squadron in regard to higher speed for fighters are concurred in. The fighter operations during these two days demonstrated the pressing need for increased speed, and for aircraft which can be easily and quickly handled on deck and in the hangar.

HMS ARK ROYAL at dusk in November 1940, from the deck of HMS SHEFFIELD.

NOVEMBER 10

With Force F safely through the Narrows, the three extra destroyers Somerville had sent to act as minesweepers came about and raced to rejoin Force H as it made its way back towards Gibraltar.

Force F merged with Cunningham’s Force A without incident. HMS Berwick and Glasgow, however, separated: they had to deliver their troops to Malta.

Things could have been worse for the convoy now entering Grand Harbour, Malta: The Italian submarine Capponi had loosed three torpedoes at HMS Ramillies. All missed.

An Italian Cant 501 seaplane.

An Italian Cant Z-501 reconnaissance aircraft of 144 Squadriglia (based at Stagnone) encountered Force A about noon. It was detected when 20 miles out, and the CAP Fulmars shot it down at 1220.

However the Italians now had enough information to attempt another attack. Radar detected a formation of 9 bombers when still 65 miles away. The Fulmars were waiting as they approached within 25 miles. This time most of the Italians managed to break through, though one was shot down. Seven were able to make bombing runs on the fleet, with HMS Valiant suffering several near misses when she was straddled by bombs.

Several empty freighters in Valetta were redesignated ME3 for their return journey to Alexandria. In the afternoon they left Grand Harbour for Suda Bay, with HMS Ramillies, Ajax and HMAS Sydney – along with a small group of destroyers – in company. After a short spring south, the convoy began to make its way eastward.

Force A was now sailing on an east-northeast course, placing it between the convoy and the Italian mainland.

A Swordfish, piloted by Charles Lamb, was flown to Malta to pick up the latest reconnaissance prints from Taranto. He was told to wait until the morning, by when the most recent batch of film could be fully processed.

HMS Illustrious, however, had serious cause for concern.

A third Swordfish had fallen into the sea.

All three aircraft had been from 819 Squadron. All of the remaining aircraft were ordered to drain their fuel tanks. It was found to be contaminated with water, sand and fungus. The fuel had been transferred from the tanker Toneline in Alexandria into just one of Illustrious’ fuel storage tanks. Fortunately there was adequate stocks remaining in the remaining tanks to keep all her air group flying.

But would just 21 Swordfish be enough?

HMS ILLUSTRIOUS with Fulmars and Swordfish spotted ready for take-off on her aft deck.

NOVEMBER 11

By the morning of the 11th, the Supermarina’s commanders were beginning to relax. In the previous few days, Royal Navy ships seemed to be everywhere, headed every-which-way.

But now most of their reported tracks were away from home waters.

Force H was well on its way home, last reported about 150 miles northwest of Bizerte.

They knew Force F had joined Force A and was now about 100 miles east of Malta.

They also knew convoy ME3 was about 100 miles south of Force A, headed towards Alexandria.

Whether through a relaxing of tension, or through the fatigue and discouragement of its reconnaissance pilots due to their expensive operations of the previous few days, the Italians began to lose track of the RN ships.

A bomber squadron sent to attack Force A was unable to find its target.

Charles Lamb took to his Swordfish at dawn to deliver the reconnaissance prints (and a bag of spuds) to an anxiously waiting Admiral Lyster and Captain Boyd aboard Illustrious. Not long after followed the three Fulmars from Ark Royal. These would land aboard Illustrious to supplement her defences.

The RAF reconnaissance aircraft remained busy through the day. Taranto had been visited by 431 Squadron at first light. The hastily developed report revealed all six of Italy’s active battleships were still sitting quietly in Mar Grande. RAF reconnaissance aircraft would maintain a presence well south of the harbour all day, watching for any movement.

It was now Cunningham would put his plans for Operation Judgement into effect.

F.A.A. Attack on Taranto:

R.A.(A)’s Orders to Illustrious and Escort Force, 11th November 1

When detached, Illustrious will adjust course and speed to pass through position “X”, 270° K ab b o Point 40, at 2000, when course will be altered into wind and speed adjusted to give speed of 30 knots. On completion of flying off first range, course will be altered 180° to starboard, speed 17 knots and a second alteration of 180° to starboard will be made to pass again through position “X” at 2100 when course and speed will be adjusted as before.

On completion of flying off second range, Illustrious will alter course to 150°, 17 knots and subsequently to pass through position “Y” , 270° K ab b o Point 202, at 0100 when course will be altered into wind and speed adjusted to wind and speed o f 25 knots to be maintained till both ranges have landed on. If there is an easterly wind it may be necessary to reverse the course between flying on first and second ranges, in which case both turns will be to starboard and speed o f ship down wind 25 knots. On completion o f landings, course will be altered to return to C .-in-C., speed 18 knots. All the above and any other alterations o f course necessary without signal.

Normal night zigzag will be maintained, except during flying operations.

If enemy surface forces are encountered during the night Illustrious is to withdraw, remainder are to engage under C.S.3. Two destroyers are to be detailed to withdraw with Illustrious.

At noon a group, designated Force X and commanded by Admiral Pridham-Wippell, was formed from the cruisers HMAS Sydney, HMS Orion and HMS Ajax along with the destroyers Mohawk and Nubian. This force would run ahead and to the left of the track HMS Illustrious would take later the same day as the carrier made its way toward Taranto.

The intention was for these cruisers and destroyers to be sighted first and act as a ‘magnet’ for any follow-up reconnaissance efforts. If not detected, they would pass through the narrow Straits of Otranto and into the Adriatic Sea in search of targets of opportunity – again as a diversion.

At 18:00 hours, HMS Illustrious was detached along with a screen including the cruisers Berwick, York, Glasgow and Gloucester and four destroyers. This would simply be designated “Strike Force”. She was scheduled to reach her flying-off point – designated Point X - some 40 nautical miles west-southwest of the island of Cephalonia and 170 nautical miles from Taranto at 20:00.

As the carrier and her escorts pulled away from Force A, Admiral Cunningham signalled Rear Admiral Lyster:

“Good luck then, to your lads in their enterprise. Their success may well have a most important bearing on the course of the war in the Mediterranean.”

One of the reconnaissance photographs delivered to HMS ILLUSTRIOUS the day before Operation Judgement.

OPERATION JUDGEMENT

“During the final briefing Commander George Beale had drawn our attention to all these installations in infinite detail when outlining the methods of attack, and when he said, “And now for the return trip,’ ‘Blood’ Scarlett’s rough voice boomed out: ‘Don’t let’s waste valuable time talking about that!’ and we all laughed. It was a typical ‘Blood’ Scarlett remark; but as it turned out he was to be one of four present who were destined not to return.”

As dusk fell, an RAF Sunderland passed near Taranto for a final look. It reported the five Italian battleships were still anchored - and that they had even been joined by a sixth.

It was an ideal opportunity.

The final version of the attack plan called for two waves of attacks by Swordfish separated by one hour.

Every pilot had been briefed on the location of ships, defences and obstacles. The best likely corridors of approach had been determined, but it would be up to each pilot to choose the most suitable course for their given mission.

FIRST WAVE

A torpedo is wheeled up to a Swordfish aboard HMS ILLUSTRIOUS

Torpedo bombers: (1x 18in Mk XII torpedo)

L4A: Lt. Cdr. Pilot K. Williamson, Observer Lt. N. Scarlett, 815 Squadron

L4C: S/Lt P.D. Sparkle, S/Lt A. L. Neale, 815 Squadron

L4R: S/Lt A. Macaulay, S/Lt A. Wray, 815 Squadron

L4K: Lt N. Kemp, Lt G.W. Bailey, 815 Squadron

L4M: Lt H. Swayne, S/Lt J. Buscall, 815 Squadron

E4F: Lt M. Maund, S/Lt W. Bull, 813 Squadron

Bombers: (6x 250lb bombs)

L4L: S/Lt W. C. Sarra, Mid. J. Barker, 815 Squadron

L4H: S/Lt A. Forde, S/Lt A Mardel-Ferreira, 815 Squadron

E5A: Capt O. Patch RM, Lt. D. Goodwin, 824 Squadron

E5Q: Lt J. Murray, S/LT S. Paine, 824 Squadron

No return address... 250lbs bombs arrayed on HMS ILLUSTRIOUS' dek during the 'bombing-up' process shortly before the attack on Taranto.

Flare/bombers: (16x flares, 4 250lb bombs)

L4P: Lt L. J. Kiggell, Lt. H. Janvrin, 815 Squadron

L5B: Lt. C. Lamb, Lt. K. Grieve, 819 Squadron

It was hoped the first wave would have a measure of the element of surprise. For this reason, with Illustrious’ now diminished Swordfish group, it would be the stronger force. Twelve aircraft would take part – 10 from Illustrious and 2 from Eagle. Half would carry torpedoes; two would carry a mix of four 250lb bombs and 16 parachute flares, while the remainder would heft six bombs.

The flares were to be dropped in an oblique line to the south-east, opposite the torpedo-carriers lines of approach across the Mar Grande. This was to both provide a diversion, as well as present the anchored ships as clearly defined silhouettes. Once their flares were exhausted, they were to drop their bombs on the harbours’ oil storage facilities.

The dedicated bombers were to hit the cruisers and destroyers lined up in the Mar Piccolo, as well as the adjoining seaplane base. Shallow dives were considered all that was needed: there were barrage balloons about, after all.

“Cruising along quietly at about five thousand feet, waiting for Kiggell to begin the flare-dropping, I realised that I was watching something which had never happened before in the history of mankind, and was unlikely to be repeated ever again. It was a ‘one-off’ job.”

FIRST WAVE: LAUNCH

The three-quarters moon was bright. But there was a thick scatter of cloud drifting by at 8000ft.

The 12 Swordfish sat on the darkened deck. The torpedo bombers identifiable by their odd hunchback appearance caused by the extended-range tank in their cockpits, while the bombers had their tanks slung between their wheels.

Illustrious had turned into the wind and was making 28 knots – with the headwind of two knots bringing the total over-deck speed to 30knots. The objective was to put a Swordfish into the air once every 10 seconds – just enough time for the prop wash to dissipate.

A green lamp flickered from Illustrious’ island.

The mission was underway.

By 20:40, all 12 Swordfish were in the dark sky. Seventeen minutes later, they finished gathered into their “Vic” formations while circuiting some eight miles from the carrier, and set course for Taranto now just 170 miles away.

Flight time was expected to be two hours and 20 minutes at a cruising speed of 75mph while at 6000ft. But the clouds proved bothersome.

By 21:15 the Swordfish formation was becoming ragged. One aircraft had lost sight of the formation. Another three, still in company, had become detached from the main body.

Lieutenant Maund in E4F recalled this tense time:

We have now passed under a sheet of alto-stratus cloud which blankets the moon, allowing only a few pools of silver where small gaps appear. And, begob, Williamson is going to climb through it! As the rusty edge is reached I feel a tugging at my port wing, and find that Kemp has edged me over into the slipstream of the leading sub-flight. I fight with hard right stick to keep the wing up, but the sub-flight has run into one of its clawing moments, and quite suddenly the wing and nose drop and we are falling out of the sky. I let her have her head, and see the shape of another aircraft flash by close overhead. Turning, I see formation lights ahead, and climb after them, following them through one of the rare holes in this cloud mass. There are two aircraft sure enough, yet when I range up alongside, the moon’s glow shows up the figure “5A” – that is Olly (Patch). The others must be ahead. After an anxious few minutes, some dim lights appear amongst the upper billows of the cloud, and opening the throttle we lumber away from Olly after them. Poor old engine – it will be getting a tanning this trip.

Then, far ahead, Taranto lit up like a firework display.

Lieutenant M. R. MAUND, RN, of E4F, Eagle's 824 Squadron

The klaxon has gone and the starters are whirring as, stubbing out our cigarettes, we bundle outside into the chill evening air. It is not so dark now, with the moon well up in the sky, so that one can see rather than feel one’s way past the aircraft which, with their wings folded for close packing, look more like four-poster bedsteads than front-line aeroplanes.

Parachute secured and Sutton harness pinned, the fitter bends over me, shouts ‘Good luck, sir’ into my speaking-tube, and is gone. I call up Bull in the back to check intercom— he tells me the rear cockpit lighting has fused— then look around the orange-lighted cockpit; gas and oil pressures O.K., full tank, selector-switches on, camber-gear set, and other such precautions; run up and test switches, tail incidence set, and I jerk my thumb up to a shadow near the port wheel. Now comes the longest wait of all. 4F rocks in the slip-stream of aircraft ahead of her as other engines run up, and a feeling of desolation is upon me, unrelieved by the company of ten other aircraft crews, who, though no doubt entertaining similar thoughts, seem merged each into his own aircraft to become part of a machine without personality; only the quiet figures on the chocks seem human, and they are miles away.

The funnel smoke, a jet-black plume against the bright-starred sky, bespeaks of an increase in speed for the take-off; the fairy lights flick on, and with a gentle shudder the ship turns into wind, whirling the plan of stars about the foretop.

A green light waves away our chocks, orders us to taxi forward; the wings are spread with a slam, and as I test the aileron controls, green waves again. We are off, gently climbing away on the port bow where the first flame-float already burns, where the letter ‘K’ is being flashed in black space. Here— in this black space— I discover Kemp, and close into formation; here also Kemp eventually gains squadron formation on Wilkinson, and the first wave is upon its way, climbing towards the north-west. At first the course is by no means certain, in fact Wilkinson is weaving, and station-keeping is a succession of bursts of speed and horrible air clawings, but in five minutes we have settled down a little. At 4,000 feet we pass through a hole in scattered cloud— dark smudges above us at one moment, and the next stray fleece beneath airwheels filled with the light of a full moon.

“‘I think our hosts are expecting us’, I said to Grieve down the tube. ‘They don’t seem very pleased to see us,’ said Grieve, and it was the last thing he could say for some time to come, and for what must have been a very uncomfortable interval as a passenger in an open cockpit above a volcano.”

FIRST WAVE: ARRIVAL

Why Taranto's defences were already blazing away into the sky even before the Swordfish arrived is the subject of much disagreement. Possibly because the harbour sounded three air-raid warning in the lead up to the attack.

The first was about 20:00 when a diaphone (sound detector) picked up distant engines. Alarms sounded and Taranto's citizens went to their shelters. A few shots were fired into the air at random - and 10 minutes later the all clear was sounded.

An hour later the sirens went off again, this time likely due to the high-flying 228 Squadron RAF Sunderland having one last look at the harbour. Italy had no night fighters to respond with.

Some accounts also blame this aircraft for the third Taranto alarm at 22.50. But the Swordfish pilots themselves believe it was Ian Swain in the Swordfish L4M that had become separated earlier. Believing he had fallen behind the main force, he sped up – arriving a full 15 to 25 minutes ahead of the main body.

Charles Lamb, the pilot aboard L5B, recalled:

Almost as soon as we were airborne we had to climb through heavy cumulus cloud, and when we emerged into the moonlight at 7,500 feet only nine of the twelve aircrafts’ lights were in sight. When the others were unable to find their leader they flew direct to Taranto. One of them was Ian Swayne, who flew at sea level and reached the target area fifteen minutes before anyone else. He had no wish to be the first uninvited guest of the Italian Navy in Taranto, and for a quarter of an hour he flew to and fro, keeping the harbour in sight waiting for the main strike. There was nothing else he could do but, of course, his presence had been detected by the Italian listening devices, and as a result all the harbour defences and the ships had been alerted… For the last 15 minutes of our passage across the Ionian Sea Scarlett had no navigational problems, for Taranto could be seen from a distance of 50 miles or more, because of the welcome awaiting us. The sky over the harbour looked as it sometimes does over Mount Etna, in Sicily, when the great volcano erupts. The darkness was being torn apart by a firework display which spat flame into the night to a height of nearly 5,000 feet. “They don’t seem very pleased to see us,” said Grieve. As he spoke “Blood” Scarlett’s dimmed Aldis light flashed the breakaway signal to Kiggell and me, telling us to start adding to the illuminations over the crowded harbour.’

“Before the first Swordfish had dived to attack, the full-throated roar from the guns of the battleships and the blast from the cruisers and destroyers made the harbour defences seem like a side-show; they were the ‘lunatic fringe’, no more than the outer petals of the flower of flame which was hurled across the water in wave after wave by a hot-blooded race of defenders in an intense fury of agitation, raging at a target which they could only glimpse for fleeting seconds...”

FIRST WAVE: FLARES

The gunners around San Viteo to Taranto harbour’s south-east were blazing away as the Swordfish arrived at 22:50 – though not at any obvious target.

Unexpectedly, no searchlights cut through the night sky.

Lamb, writing later, believed he understood why.

‘From above I could see that the opposite was the case; because the aircraft were only a few feet above sea level, the use of searchlights would have floodlit the six battleships and the harbour defences, and greatly assisted the attacking aircraft in selecting their target…

At 22:56, Williamson signalled the aircraft of the first wave to break formation and head for their individual targets. The flare-dropping flight separated from the main body, nosing eastward over the balloon barrage.

It was just 23:02 when Swordfish L4P (Kiggell and Janvrin) completed deploying its bright-yellow parachute flares at 4500 feet and half a mile apart. Each flare had fallen 1000ft before igniting.

Instantly, Taranto’s high-angle defences opened up.

Janvrin, L4P’s Observer, would write:

We had a grandstand view, as we didn’t go down to sea level. We dropped our flares at about 8,000 feet … and in fact we were fired at considerably. We had a fair amount of ackack fire], and most extraordinary things that looked like flaming onions – one just sort of went through it, and it made no great impression. One didn’t think that they would ever hit you – there was always fear but I think in the same way that one has butterflies in the tummy beforehand, but when things are actually happening you don’t seem to notice the butterflies much.

The big guns banged away at the flares in an attempt to both extinguish them and knock down any aircraft believed flying among them. Their bright tracer shells, nicknamed ‘flaming onions’, served only to help illuminate the harbour for the attackers. In the course of the whole battle, they hit nothing.

The Italian warships quickly discarded their orders.

Lieutenant M. R. MAUND, RN, of E4F, Eagle's 824 Squadron

Years later. Some quaint-coloured twinkling flashes like liver-spots have appeared in the sky to starboard. It is some time before I realise their significance; we are approaching the harbour; and the flashes are HE shells bursting in a barrage on the target area. We turn towards the coast and drop away into line astern, engines throttled back. For ages we seem to hover without any apparent alteration; then red, white, and green flaming onions come streaming in our direction, the HE bursts get closer, and looking down to starboard I see the vague smudge of a shape I now know as well as my own hand. We are in attacking position. The next ahead disappears as I am looking for my line of approach, so down we go in a gentle pause, glide towards the north-western corner of the harbour. The master-switch is made, a notch or two back on the incidence wheel, and my fear is gone, leaving a mind as clear and unfettered as it has ever been in my life. The hail of tracer at 6,000 feet is behind now, and there is nothing here to dodge; then I see that I am wrong, it is not behind any more. They have shifted target; for now, away below to starboard, a hail of red, white, and green balls cover the harbour to a height of 2,000 feet. This thing is beyond a joke.

A burst of brilliance on the north-eastern shore, then another and another as the flare-dropper releases his load, until the harbour shows clear in the light he has made. Not too bright to dull the arc of raining colour over the harbour where tracer flies, allowing, it seems, no room to escape unscathed.

We are now at 1,000 feet over a neat residential quarter of the town where gardens in darkened squares show at the back of houses marshalled by the neat plan of streets that serve them. Here is the main road that connects the district with the main town. We follow its line and as I open the throttle to elongate the glide a Breda swings round from the shore, turning its stream of red balls in our direction. This is the beginning.

Charles Lamb, in his flare deploying role, described himself thus: “For an unforgettable half-hour I had a bird’s eye view of history in the making”. He went on to paint the opening moments of the battle:

Before the first Swordfish had dived to the attack, the full-throated roar from the guns of six battleships and the blast from the cruisers and destroyers made the harbour defences seem like a side-show... From my position astern of Kiggell and Janvrin I was in no danger whatever and could watch proceedings at leisure. I have never been in less danger in any attack than I was that night, when the rest of the squadron were flying into the jaws of hell. I was convinced that none of the torpedoing aircraft could have survived.

From his vantage point Baily (L4K) reported seeing gunfire from the cruisers – aimed at the low flying Swordfish below – hitting nearby merchant vessels. The Italians realised their error, and began aiming a little higher. The Swordfish were therefore able to approach under this umbrella of fire.

“I watched it wing its way through the harbour entrance five thousand feet below and disappear under the flak, and imagined that it had been shot down at once. Then I saw the lines of fire switching round from both sides, firing so low that they must have hit each other. The gun aimers must then have lifted their arc of fire to avoid shooting at each other, and I saw their shells exploding in the town of Taranto in the background. The Italians were faced with a terrible dilemma: were they to go on firing at the elusive aircraft right down on the water, thereby hitting their own ships and their own guns, and their own harbour and town, or were they to lift their angle of fire still more?”

FIRST WAVE: TORPEDO ATTACK

As the first flares erupted into life, Williamson and Scarlett (in L4A) led his sub-flight of L4C (Sparkle and Neale) and L4R (Macaulay and Wray) had cut their engines in a gentle dive from 5000ft to sea level. It was hoped their quiet engines would cause them not to be noticed until after passing over the outer harbour batteries.

They had to fly – at just 30ft - through the balloon cables strung out on Diga di Tarantola mole to the south-west of the battleship anchorage before flying up the centre of Mar Grande.

L4A was never seen again. By the British.

The Italian destroyer Fulmine reported sighting by moonlight a Swordfish diving at high speed. The warship opened fire from about 1000 yards, but observed L4A to release its torpedo which then ran on to hit the battleship Cavour. The Swordfish fell into the water near a floating dock. Both Williamson and Scarlett were made prisoners.

Scarlett later wrote:

We put a wing-tip in the water. I couldn’t tell. I just fell out of the back into the sea. We were only about 20 feet up. It wasn’t very far to drop. I never tie myself in on these occasions. Then old Williamson came up a bit later on and we hung about by the aircraft which still had its tail sticking out of the water. Chaps ashore were shooting at it. The water was boiling so I swam off to a floating dock and climbed on board that. We didn’t know we’d done any good with our torpedoes. Thought we might have, because they all looked a bit long in the face, the Wops.

Swordfish L4C (Sparkle) and L4R (Macaulay) had crossed the Diga di Tarantola mole shortly after their leader, looking for targets. Both aircraft passed low between the destroyers Lampo and Belena as L4A’s torpedo detonated against Cavour.

Both also loosed their torpedoes at Cavour. Both missed. Andrea Doria, to Cavour’s north-east, reported two close explosions at 23:15. This was almost certainly the two torpedoes detonating at the end of their runs.

L4C and L4R completed 180-degree turns while under heavy fire, and successfully passed back out of Mar Grande to the safety of the open sea as they had come in.

The lone Swordfish L4M (Swyane) which had been loitering outside the harbour after becoming separated from the main flight saw the flares being dropped. He now entered Mar Grande at 23:15 from further to the north, passing over the submerged breakwater at 1000ft. After losing height while racing over the harbour, Swayne noted that most of the flak was passing over his head, and that no searchlights had been activated.

Lieutenant M. R. MAUND, RN, of E4F, Eagle's 824 Squadron

... another two guns farther north get our scent— white balls this time— so we throttle back again and make for a black mass on the shore that looks like a factory, where no balloons are likely to grow. A tall factory chimney shows ahead against the water’s sheen. We must be at a hundred feet now and soon we must make our dash across that bloody water. As we come abreast the chimney I open the throttle wide and head for the mouth of the Mare Piccolo, whose position, though not visible, can be judged by the lie of the land. Then it is as though all hell comes tumbling in on top of us— it must have been the fire of the cruisers and Mare Piccolo canal batteries— leaving only two things in my mind, the line of approach to the dropping position and a wild desire to escape the effects of this deathly hailstorm.

And so we jink and swerve, an instinct of living guiding my legs and right arm; two large clear shapes on our starboard side are monstrous in the background of flares. We turn until the right-hand battleship is between the bars of the torpedo-sight, dropping down as we do so. The water is close beneath our wheels, so close I’m wondering which is to happen first— the torpedo going or our hitting the sea— then we level out, and almost without thought the button is pressed and a jerk tells me the ‘fish’ is gone.

We are back close to the shore we started from, darting in and out of a rank of merchant ships for protection’s sake. But our troubles are by no means over; for in our dartings hither and thither we run slap into an Artigliere-class destroyer. We are on top of her fo’c’s’le before I realise that she hasn’t opened fire on us, and though I am ready for his starboard pompom, he was a sitting shot at something between fifty and a hundred yards. The white balls come scorching across our quarter as we turn and twist over the harbour; the cruisers have turned their fire on us again, making so close a pattern that I can smell the acrid smoke of their tracer. This is the end— we cannot get away with this maelstrom around us. Yet as a trapped animal will fight like a fury for its life, so do we redouble our efforts at evasion. I am thinking, ‘Either I can kill myself or they can kill me,’ and flying the machine close down on the water wing-tips all but scraping it at every turn, throttle full open and wide back.

Soon the shape of the battleship Littorio suddenly loomed out against the backdrop of flares and tracer fire. Making a hard turn to port, L4M dropped its torpedo at just 400 yards. Swayne was forced to heave his Swordfish between Littorio’s masts. It was a good shot. The torpedo detonated against Littorio’s port side.

Almost the same time, a second torpedo exploded on her starboard bow. This had been dropped by L4K (Kemp) which had entered Mar Grand from even further north – following the coast to the inner harbour, swinging south before loosing at Littorio. Kemp would, like several other pilots, report shells from nearby cruisers passing over his head before falling among merchants on the opposite side of the harbour.

E4F (Eagle’s Maund and Bull) had been following L4K. Dropping its torpedo in almost the same place, this weapon missed Littorio but tracked Vittorio Veneto – until it struck the bottom and buried itself in the mud. Banking hard to starboard to avoid two cruisers, Maund instead found himself flying at cockpit-level with the anti-aircraft guns of the destroyer Gioberti. They did not fire. Zigzagging madly, Maund eventually reached the open sea:

Bull, ‘My Christ, Bull! Just look at that bloody awful mess! Just look at it!’

All but L4A safely made it back out of the harbour.

“... other spidery biplanes dropped out of the night sky, appearing in a crescendo of noise in vertical dives from the slow-moving glitter of the yellow parachute flares. So, the guns had three levels of attacking aircraft to fire at...”

FIRST WAVE: BOMB ATTACK

Meanwhile, E5A, E5Q and L4H had been choosing from a wealth of targets in the crowded Mar Piccolo, the tank farm and the seaplane base.

E5A was following the flare droppers by just a few minutes. Circling above the exploding barrage fire from 8500ft and crossing the harbour to the south-east, E5A eventually spotted the heavy cruisers Trieste and Bolzano. The pilot, Patch, kicked his bomber into a dive – released his bombs (one of which had a Royal Marine boot strapped to it) – and was forced to dodge behind a hill and weave close among the rooftops of Taranto itself to evade an intense barrage of following gunfire.

The captains of the three heavy cruisers – Trento, Trieste and Bolzano – soon realised their ships were lost among the gloom of the central harbour. They ceased fire and let the darkness shield them.

L4L (Sarra and Bowker) had flown in to Mar Grande from over Cape Rondinella at about 8000ft before diving to 1500ft – tracked all the way by defensive gunfire. Unable to spot their primary target – the cruisers – amid the maelstrom, L4L instead singled out the seaplane base. All of the Swordfish’s load of 250lbs bomb exploded among the hangars, storehouses and slipway. Two seaplanes were destroyed.

L4H (Forde and Mardel-Ferreira) had lost contact with its sub-flight during the approach to Taranto, but had attached itself to Williamson’s torpedo bombers. As the torpedo bombers swept downwards, Forde passed directly over the battleship anchorage on his way to Mar Piccolo. Dropping to 1500ft for better visibility, he failed to see the heavy cruisers. So he dropped his six bombs in the tightly-packed vicinity of what appeared to be two light cruisers and several destroyers. Uncertain his bombs had released, Forde made a second pass – and emerged from the firestorm unscathed.

First bomb fell in water short of the two 8-inch cruisers. During the dive intense AA fire was suffered. The pilot was not sure that his bombs had dropped, so turned round in the western part of the Mar Piccolo and repeated the attack.