“Admiral King’s attitude has sometimes been ascribed to anglo-phobia. This is not altogether true. Certainly the Admiral’s loyalty was given whole-heartedly to the Navy he served. It was a feeling which led him to look upon even the United States Army and Air Force as little better than doubtful allies.”

The British Pacific Fleet was born in a maelstrom of political compromise.

But expediency also played its part.

The Royal Navy had repeatedly turned down pleas for support from US chief of naval operations Admiral Earnst King during 1942 and 1943. It argued that its few fleet carriers were already too thinly stretched across the Arctic, North Atlantic, Mediterranean and Indian Ocean theaters.

But, with the Italian fleet surrendered and the remaining units of the German navy neutralised, Britain was forced to turn her attention towards her responsibilities in the Far East.

The side-show that had been called Admiral Sommerville’s Eastern Fleet could no longer be justified, and increasing numbers of effective capital ships and carriers were now slowly being committed.

As early as January 4, 1944, Admiral Sir Percy Noble, head of the British Admiralty Delegation in Washington, began advocating the deployment of a British Pacific Fleet.

Noble went on to tell Admiral King the Royal Navy did not need its carriers for Operation Overlord, the invasion at Normandy. He also pointed out that the targets available in South Asia were barely worth the effort. He proposed the deployment of two armoured carriers supported by the heavily updated battlecruiser HMS Renown out of the Eastern Fleet to operate under US control in the Pacific.

The idea met a frosty reception. It was rejected outright.

Vice-Adrmiral Philip Vian, who would command the British Pacific Fleet's carriers, outlined the political wrangle in his autobiography, Action This Day:

Vice-Admiral Philip Louis Vian

Vice-Admiral Philip Louis Vian

Difficulties soon arose. Mr Churchill noticed that the American Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Ernest King, was by no means enthusiastic over British participation. Admiral King felt that any of our forces available after the campaign in Europe had been provided for, would be best employed against Japanese oil supplies in the islands bordering the Indian Ocean. If they joined the Pacific war, they should operate in General MacArthur’s South-West Area.

Admiral King’s attitude has sometimes been ascribed to anglo-phobia. This is not altogether true. Certainly the Admiral’s loyalty was given whole-heartedly to the Navy he served. It was a feeling which led him to look upon even the United States Army and Air Force as little better than doubtful allies. It was perhaps engendered in some degree by jealousy of the Royal Navy, which had for so long dominated the oceans of the world. Now, when the United States Navy had outstripped our own in size and importance, and was poised to deliver, unaided, decisive defeat on the Japanese Fleet, it was understandable that King should want no one else to share his laurels.

Admiral King pushed hard for the British carriers to step up their attacks against South Asia and the Bay of Bengal in an attempt to divert Japanese aircraft out of the central Pacific. But he also quietly canvassed the idea of assigning a British fleet to the command of General MacArthur. MacArthur, however, was to prove no less obstinate than himself.

But the concept of a British Pacific Fleet operating under USN command continued to grow. Even Winston Churchill, with his “Germany First” mantra, was forced to acknowledge this shift in the naval war.

On September 28, 1944, Churchill would report to parliament:

“The new phase of the war against Japan will command all our resources from the moment the German War is ended. We owe it to Australia and New Zealand to help them remove for ever the Japanese menace to their homelands, and as they have helped us on every front in the fight against Germany we will not be behindhand in giving them effective aid.

“We have offered the fine modern British fleet and asked that it should be employed in the main operations against Japan. For a year past our modern battleships have been undergoing modification and tropicalisation to meet wartime changes in technical apparatus. The scale of our effort will be limited only by the available shipping.”

The task of turning these grand words into a reality was to fall on Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser.

He was under no illusions as to the difficulty of the task ahead:

“It was quite clear that in the intensive, efficient and hard striking type of war that the US fleet was fighting, nothing but the inclusion of a big British force would be noticeable and nothing but the best would be tolerated.”

It became immediately clear that, despite Churchill’s words, the ships allocated to the British Pacific Fleet had not been fully tropicalised - if at all - and few had the most modern equipment.

The escort carrier Ommaney Bay burns after being hit by a kamikaze.

“Fraser considered this experience essential … being the man that he was… could not order the British Pacific Fleet to brave the kamikaze menace without having experienced the same danger himself.”

A taste of things to come

In anticipation of the deployment of the British Pacific Fleet, Admiral Fraser went on a tour of United States operations. After talks with Admiral Nimitz, Admiral Fraser flew to Leyte to meet General MacArthur.

On his arrival he was invited to watch a US Marine assault on Lingayen Gulf. Admiral Fraser readily accepted the opportunity to observe the landing operation.

He, along with his staff and observers, were taken aboard the flagship USS New Mexico on January 2.

Four days later he would be personally introduced to the kamikaze scourge.

Admiral Fraser would write:

MacArthur asked me if I would like to go up and see the Lingayen Gulf landings in the Philappines. So I went. I took my flag lieutenant and my secretary with me. We embarked in this American battleship and went up with the landing party. About halfway there, these kamikazes started to come down. One sank an American carrier just alongside us. Having no armoured flight deck, of course , she went up in flames. Then next morning a kamikaze came down on us, on to the front side of the bridge...

Fraser's first sight of the terrifying new suicide bombing tactic was to be on January 4. A characteristic massed attack was made on the fleet in the waters off Luzon. The escort carrier USS Ommaney Bay was damaged so severely she had to be abandoned and eventually sunk.

But it was January 6 when New Mexico herself would become the subject of a kamikaze attack. While steaming inshore to join a bombardment force pounding the landing site, a kamikaze embedded itself into the port side of the battleship's bridge.

Moments earlier, Fraser had been standing in that very spot. The admiral had been called over to the other side of the bridge to see part of the amphibious landing action unfold - leaving behind him Churchill's personal representative, General Sir Herbet Lumsden.

ON ‘CRASH BOMBING’

Commander Frank Hopkins, Royal Navy

air observer liaison

Stationed with the USN during the battle for Leyte Gulf at the end of 1944, Hopkins wrote this assessment of the effect of kamikaze’s on US carriers:

The two sources of damage are the petrol tanks in the plane and the bomb. The petrol tanks normally ignite on the flight deck, setting fire of the aircraft in the vicinity, and burning petrol flows through holes in the deck, starting fires among the aircraft below. The bomb, being unable to penetrate the armoured hangar deck, explodes somewhere between that deck and the flight deck, usually causing considerable casualties from splinters in the various ready rooms and offices under the flight deck, and starting fires amongst planes on the hangar deck

Once the fires are well started, considerable trouble is caused from smoke. This becomes a serious handicap to firefighters and causes casualties from suffocation. The combination of burning rubber, lubricating oil and petrol makes the smoke very dense and evil smelling. Since the air intakes for most of the ventilation are in the hangar, this smoke penetrates everywhere...

Flag Lieutenant Vernon Merry, who was on Admiral Fraser’s staff, would write:

“I was knocked flat … but I was all right behind armour. The C-in-C was on the other side. I tried to fight my way out of the Plot… it was difficult to get out in the chaos, with fire and dead bodies everywhere outside. I found him (Admiral Fraser) at the side; he’d been worrying about me, knowing that the others were dead.”

Admiral Fraser was unhurt. But General Lumsden was killed in the blast, along with many of New Mexico's bridge crew. Admiral Fraser's secretary also was among the dead. In all 30 were killed and 87 wounded in the attack that also claimed the life of New Mexico's commanding officer.

ICY RECEPTION: MIXED MESSAGES FROM THE US

“(If we) allow the British to limit their active participation to recapture areas that are to their selfish interests alone and not participate in smashing the war machine of Japan ... we will create in the United States a hatred for Great Britain ... that will defeat everything that men have died for in this war”

Not least among the newly formed British Pacific Fleet’s hurdles was the divided attitude towards it among the politicians, people and military commanders of the United States.

Some held worthy concerns about the ability of the British to maintain the style of fast, long-distance operations the USN was conducting. Others were incapable of seeing anything to do with the “old country” through other than the distorting lens of contempt.

Regardless of this, President Roosevelt was keen to prove to his voting public that it would not be a fight in which US blood would exclusively be shed. Several key media players backed this stance.

Fortunately for the British Pacific Fleet, the Admirals “on the water” held little – if any – of the bias being displayed by their commanders in Washington.

Instead, they recognised that the Royal Navy had been fighting non-stop since 1939 and had a wealth of experience – and equipment – which could prove uniquely valuable in the hard slog to neutralise Japan.

But Admiral Nimitz, nevertheless, was not initially convinced that the Royal Navy was needed.

HMS Anson in Sydney, 1945

Rear-Admiral Vian recalled the situation:

Meanwhile Admiral Fraser, appreciating fully the great importance, from a national point of view, of the Royal Navy engaging in the most modern type of sea warfare in company with the Americans who had perfected it, had been striving to convince Admiral Nimitz that the British would not only be able to operate alongside the Americans without calling on them for logistic aid, but that their Fleet would be of real help in the task which lay ahead – defeating Japan. He found that, like Admiral King, Admiral Nimitz felt that the fast United States carrier striking forces were perfectly capable of dealing, on their own, with the operations contemplated for the final reduction of the enemy…

Admiral Fraser set himself to break down opposition. At the same time he realised that nothing but a really powerful Fleet could pull its weight alongside the great forces the Americans were using. Nothing but the very best would be expected by our Allies, who were by this time experienced veterans in the new forms of ocean warfare. It is a measure of his success that, when at length the British Pacific Fleet joined the Americans, they were greeted by a signal from Admiral Nimitz: “The British force will greatly increase our striking power, and demonstrate our unity of purpose against Japan. The United States Pacific Fleet welcomes you.”

Admiral Fraser wrote fondly of an instance which would set the scene for the relationship of mutual respect and support that would feature in operations between Task Force 57 and 58:

“I remember very well when I first went over to see Admiral Nimitz in Honolulu. At the end of our talks I was congratulating him on what the American fleet had done. He said, “Yes, I think we have done very well. There’s only one thing we envy you, and that is your British traditions.” I was very surprised and said, “Do you really think so, Admiral?” “Yes,”, he said, “it’s the thing you've got which can neither be bought nor sold. Guard it with your lives.” I always remember that. Wonderful thing for an American admiral to say.”

CHAINS OF COMMAND

“There was, however, another and better reason why Admiral King was opposed to the Royal Navy joining the Pacific War. While the Royal Navy had been operating in, and trained and equipped for the relatively short range warfare of the Mediterranean, Home Waters and the Atlantic, an entirely new form of campaigning had been evolved in the vast spaces of the Pacific…”

Despite Nimitz’s changed sentiments, politics would present a continuous series of hurdles. Many were minor, some were serious. All were about “saving face” - regardless of the side they originated from.

As Admiral Nimitz commanded the US Pacific Fleet from his base in Pearl Harbour, Admiral Fraser was faced with the potentially embarrassing situation of being the most senior admiral of both services actually at sea.

The Nelson-era tradition of commanding from the front line would have to be set aside for the sake of political expediency.

Fraser regretfully resolved to raise the flag of the British Pacific Fleet in Sydney and, in doing so, averted yet another of the many potential political crises that threatened the very future of Britain’s contribution in the fight against Japan.

Vice-Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings would now be the senior flag officer aboard the British Pacific Fleet.

He proved to be an excellent choice.

He quickly won the respect and admiration of his US counterparts. The US Liaison Officer aboard HMS King George V, Lt Cdr Robert F. Morris would write to John Winton:

Rawlings was not only a great tactician and able leader in the Royal Navy but for we Americans he fitted the traditional image of a magnificent British admiral and cultured English gentleman of the old school. It was my good fortune to be with him when our admirals Nimitz, Halsey and Spruance were also with him and I observed unmistakably their liking for him, both on social occasions and in the grim prosecution of the war.

All this time the debate raged in Washington over whether or not to accept British assistance, where, and how.

Rear-Admiral Vian recalled the depth of the debate:

Admiral King, together with the American Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, Admiral Chester Nimitz, not unreasonably doubted whether the British Fleet could develop, within a useful time, a similar system, which would enable it to operate effectively. The American logistic system, although it seemed at first sight to be most lavish, had in fact been carefully scaled to serve the American Pacific Fleet, with nothing to spare. If the British Fleet was to join forces, it must be self-supporting.

Mr Churchill’s offer was accepted, nevertheless. The British Government was determined that it should be fulfilled to the letter, and furthermore, that the British Pacific Fleet should not be delegated to operations in the “back area” of the South-West. It must take part in the main operations against Japan.

Eventually, the reluctant Americans appeared to relent – but with conditions: The Royal Navy would have to be self-sufficient when it came to provisions, ammunition and equipment. While fuel-oil would be shared from bulk stores with the USN, the RN would have to put in as much as it took out.

Quietly, USN operational commanders offered Admiral Fraser access to any excess capacity they had available and agreed to help repair battle damage in the same manner they would their own.

Task Force 113 unleashed

Admiral Fraser leapt at this first hint that approval had been granted to take part in the operations against Okinawa

It was with a huge sense of relief and achievement that the carrier force, designated Task Force 113, along with the Fleet Train, designated Task Force 112, set sail from Sydney to Ulithi Island on February 27. HMS Illustrious followed a week later after urgent repairs had been completed.

It had been no easy task to get this far. Cobbling together the Fleet Train had been an enormous effort for Britain and her allies whose merchant shipping had suffered horrendous losses in the convoy battles of the North Atlantic and Mediterranean. Now, the support group included ten repair and maintenance ships, 22 tankers, 24 store carriers, four hospital ships, five tugs, 11 general cargo vessels and two floating docks. The recreation ship Menestheus was still in the process of being fitted out, but would eventually offer a theatre, bar and a brewery.

The talk was over. The fleet was now committed. Or so it seemed

Manus Island

Manus Island had been selected as the British Fleet’s forward base. It was part of the Admiralty Group of islands north of New Guinea, and was a British protectorate.

It was during this deployment period that the British Pacific Fleet realised just what a truly difficult task lay ahead of it.

Despite Churchill’s assertions, the ships – designed to operate in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic – had not received the air-conditioning and ventilation modifications necessary for the tropical conditions.

Manus Island was a hot, humid but huge anchorage for the British Pacific Fleet. Under the equatorial sun, the armoured flight decks would absorb the heat and radiate it downwards through the hull. Those who chose to sleep on the deck at night while on “rest” breaks at Manus would remark there was little point laying out ones bedding until after 11pm because of the retained heat.

Conditions below were even worse. It was a sweatbox in which to sling out hammocks. At least on the flight deck there was a chance for a hint of a cool sea breeze early in the morning.

Officers and ratings both suffered horribly, with prickly heat, sweat rashes and boils causing long queues outside the medical offices. Even fresh water was scarce as the Fleet Train’s distillation vessel had been held up by a dockyard dispute in Sydney.

AT WAR IN THE TROPICS

A war correspondent aboard Victorious described the stay at Manus Island as:“The tropical sea war is an unending Turkish bath - with no drying room...

The long flight decks of the carriers are made of steel. They absorb the rays of the tropical sun and retain the torrid heat night and day. The heat penetrates down into the ship to meet the intense heat rising from the boiler rooms and galleys. At action stations warships are closed up, scuttles – portholes – are shut, Watertight bulkheads, which section off the ship into bootbox compartments, are locked with great iron pins. Four-fifth of an aircraft carrier’s ship’s company work sandwiched between those two layers of heat – stifled, sweating, every minute of every hour of every day and night until they are back in port. They suffer prickly heat and other skin disorders. The men of Victorious think of the damp when they were fighting in the icy cold of the Arctic and the North Atlantic. When it is freezing cold at sea you can, with many layers of clothing, at least get some warmth into your body; but out here you cannot get cool. Even the water you drink is as warm as that in which at home you would take a bath.

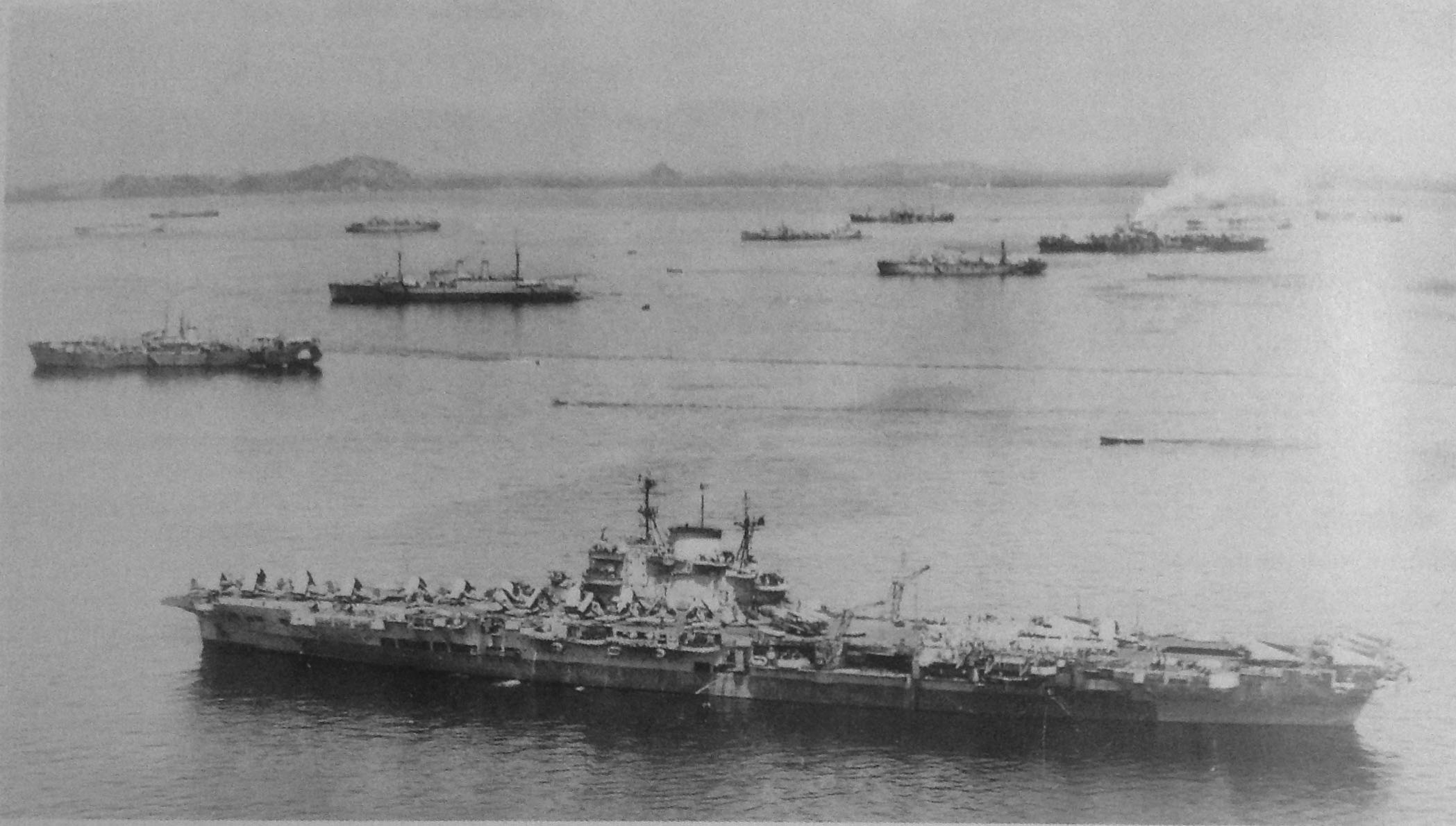

One of only a very few images of the BPF anchored at Manus. HMS VICTORIOUS in the foreground, with elements of the Fleet Train and possibly HMS INDEFATIGABLE in the background.

Rear-Admiral Vian recalled the challenge and discomfort Manus presented:

“Manus itself, and the facilities we found waiting for us, were our first disappointment. Only twenty-seven of the sixty-nine ships of all types earmarked for the Fleet Train had as yet been assembled, many having been held up by the incessant labour strikes of the Sydney waterfront. One of the missing vessels was a water-boat, so that our ships, dependent on their own condensing plants, were permanently short of water in the tropical heat. A long swell running through the great expanse of the harbour made fuelling from the tankers an uncomfortable and damaging process, in the absence of catamarans to hold the ships apart. Long journeys by boat were necessary to get from ship to ship or from ship to shore, and a chronic shortage of harbour craft, owing to lack of shipping in which to transport them from Sydney to Manus, made for a chaotic situation.

Insurmountable hurdle ... An FAA Avenger in close company with a USN Hellcat in the last weeks of the war when the two fleets worked together. Some political sectors in both the UK and US saw such close operation as something to be avoided, at any tactical cost.

Second thoughts

The British ships arrived at Manus in the Admiralty Islands on March 7 – only to discover the politics had actually intensified while it has been at sea.

Most surprisingly, the Royal Navy quickly realised it was unable to use British territory without the permission of the United States.

Task Force 113 was forced to spend another 10 days waiting as Washington once again debated what to do with them. It was obvious there was a faction of senior commanders – led by the US Navy’s Admiral King – that didn’t want the British involved in “their war”.

To keep the crews’ minds off the heat, Admiral Rawlings ordered a series of “working up” exercises. Not only would this improve the skills of the task force, it would expose them to the cooler sea air instead of the stifling stillness of the harbor.

The three carriers were already at sea, exercising, when Illustrious arrived on March 13. All four sweltered at the anchorage for the next two days before setting sail once again to practice combined airgroup operations.

As the fleet exercised and sweated, Admirals Fraser and Nimitz reaffirmed their belief that the British Pacific Fleet should act as a separate task force off Sakishima Gunto, though in close-cooperation with the United States Fifth Fleet.

RETURN OF THE ROYAL NAVY TO THE FAR EAST

- Editorial, 1945

There is even a disposition in some American naval circles, which have spent the intervening three years in learning all the intricate lessons of Pacific sea-air warfare in the hard way, to doubt whether British naval power trained under the very different European conditions, would be any great help in the Pacific. That, however, seems a rather narrow view and one which insufficiently honours the great and loyal cooperation which the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy have given our forces in the Pacific – from the tragedy of the Java Sea, when Exeter and Perth were lost along with our Houston, through the lean days in 1943, when Victorious helped our still scanty carrier forces, down to the battle around Leyte in which Shropshire and Australia played distinguished roles. None can yet afford to look askance at any reinforcements; the one question is only how to secure that integration and flexibility of command which can make the maximum use of all forces available.

Washington remained reluctant. Admirals Nimitz and Spruance dug in.

The hole in the aft section of USS Randolph's flight deck after a kamikaze attack in Ulithi harbour.

Damage to several Fifth Fleet carriers had reduced the number of operational US task groups from five to four. USS Saratoga had been badly damaged and CVE Bismark Sea sunk by kamikaze aircraft at Iwo Jima. USS Randolph had been damaged in a night kamikaze attack on the Ulithi anchorage on March 13.

Both US Admirals at the scene argued that the British were now a vital “flexible reserve” for the Fifth Feet’s operations.

But the British Pacific Fleet, despite its successful operation against Palembang, was not considered by many US commanders as being sufficiently experienced enough to join in with the direct attack on Okinawa.

Their concerns had some merit.

TYRANNY OF DISTANCE

“The number of merchant ships required for the Fleet Train in itself presented a daunting problem. The situation was aggravated by the worn-out condition of many of the fleet auxiliaries and merchant ships, which had endured five hard years of war.”

British ships, used to operating close to an extensive network of forward bases such as Gibraltar, Malta and Alexandria, did not have the extended range of their American counterparts.

The anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Phoebe, for example, was recorded as having only 55 per cent of her fuel remaining after steaming in tropical conditions for 72 hours at 16 knots, with only 10 hours at 20 knots.

Supply deliveries were more often than not too little, too late.

The fleet’s home base was in the United Kingdom, 12,000 miles away from their forward base in Sydney.

The advanced base at Leyte was, in turn, 800 miles from the combat zone.

This was the challenge that the Logistics Service faced.

And the Fleet Train assembled to support the warships was an incomplete mishmash of ships of all shapes, sizes and ages - barely suited to the task.

Waite Brooks: The British Pacific Fleet in World War II:An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George V)

We had been in Manus a week and the admiral was still in the dark as to when and where the fleet would be employed. Our proposed operational role that came out of Admiral Fraser’s December meeting with Admiral Nimitz was still awaiting Washington’s approval. The fleet could sense the indecision, and the men were restless. It was an atmosphere easily exploited by rumours and the ship buzzed with a host of wild ideas. To quell this, the captain spoke to all officers and petty officers the Monday after our arrival and urged us to kill any rumours about there being a lack of purpose or need for our presence in the Pacific. He concluded by saying, “Let the men know we are here because we have a definite job to do and are needed.” Two days later, Admiral Fraser at his headquarters in Sydney, received the long-awaited message from the American Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Report to Admiral Nimitz.”

Vice-Admiral Vian recalled the challenged face in building a supply chain which would find itself extending all the way from Britain to Sakishima Gunto:

“A further difficulty arose through the agreement which had already been made with the United States, whereby Great Britain would concentrate on building warships and certain types of specialised vessels, leaving the American shipyards to build standard merchant ships. Thus the auxiliaries we needed would have to come out of the American building programme.

Nevertheless, at the second Quebec Conference (Octagon) in September, 1944, Mr Churchill, offering the British Main Fleet to take part in operations against the Japanese under United States Supreme Command, felt able to state that an adequate Fleet Train had been built up. His information was calculated on the assumption that the Fleet would be operating, as was the American Pacific Fleet at that time, off the Philippine Islands, some 2000 miles from the chosen British main base at Sydney.

The destroyer HMS ULYSSES refuels alongside a Royal Navy auxiliary as a carrier, either HMS INDEFATIGABLE or IMPLACABLE approaches.

Vice Admiral Rawlings.

Active reserve

Eventually, a suitable compromise role was found. Task Force 113 would be allocated a chain of islands to the south-west of Okinawa proper known as Sakishima Gunto. It was to neutralise the airfields there to prevent reinforcements being flown to Okinawa from Formosa.

The British would operate semi-independently in this secondary, albeit important, interdiction role on the Fifth Fleet’s left flank.

While the task force had little chance of achieving fame or glory in such a position, it would still face the prospect of serious attack.

A carefully worded document sought to appease all parties by suggesting that all orders were to be issued in the form of “requests”, but Admiral King still prevaricated: He would wait until March 14 to ratify this agreement from his Washington offices.

After the war, King remained obstinate:

“The most desirable solution would be for the British Pacific Fleet to be assigned certain tasks in the Pacific to carry out independently, rather than for ships of the Royal Navy and the United States Navy to be maneuvered together.”

Seafires and Avengers are ranged for a strike aboard HMS IMPLACABLE. This carrier did not arrive until after the Sakishima campaign. Her Seafires can be identified by the large tear-drop drop tanks adapted from RAAF Kittyhawk stocks. HMS INDEFATIGABLE'S Seafires used the RAF's conformal "slipper" style.

Into the fire: ICEBERG ahead

Finally, on March 15, the executive signal was issued “inviting” the British Pacific Fleet to join Operation ICEBERG.

Admiral Rawlings signalled Admiral Nimitz:

“I hereby report TF 113 and TF 112 for duty in accordance with orders received from C-in-C British Pacific Fleet,” and added, “It is with a feeling of great pride and pleasure that the British Pacific Fleet joins the U.S. Naval Forces under your command.”

Admiral Nimitz replied:

“The United States Pacific Fleet welcomes the British Carrier Task Force and attached units which will greatly add to our power to strike the enemy and will also show our unity of purpose in the war against Japan .”

But Admiral King had added a catch-clause to his document accepting the services of the BPF:

COMINCH has directed that employment of Task Force 113 and Task Force 112 must be such that they can be disengaged and reallocated at seven days’ notice from him.

The threat of being relegated to the second-line operations around Borneo would continue to hang over the British task force.

Immediately approval was received from Washington, Admiral Nimitz’s staff flew to Manus to confer with Admiral Rawlings and his officers.

They brought with them some 10,000 reconnaissance images of Miyako and Ishigaki islands.

Admiral Spruance would later recall:

“In spite of the fact that Admiral Rawlings and I had had no chance for a personal conference before the operation, Task Force 57 did its work to my complete satisfaction and fully lived up to the great traditions of the Royal Navy. I remember my Chief of Staff remarking one day during the operation that if Admiral Rawlings and I had known each other for twenty years things could not have gone more smoothly.”

On March 17, the first elements of the Fleet Train departed from Manus in preparation to support the carriers which were to follow a day later. Two repair ships, two accommodation ships (the support vessels were not large enough to hold all the mechanics and engineers necessary), an aircraft repair ship and a distillation ship along with nine supply ships set sail under the watchful eye of three escort carriers and a mix of frigates.

When the British Pacific Fleet arrived off Ulithi Island in the Carolines, it joined an armada of 385 warships (including 10 battleships, 18 carriers, 12 cruisers and 136 destroyers) along with 828 assault vessels of all shapes and sizes.

Sakashima Gunto

Immediately, the admirals, captains, flight commanders and their respective assistants set about planning.

The sudden deluge of intelligence information and operational orders were almost overwhelming.

HMS Victorious’ Captain Denny would comment:

“Serial orders issued by the numerous British authorities, the American manuals, the operations orders, the intelligence material all relevant to the operation, reports and returns due, when piled on my sea-cabin desk reached to the deck-head”

But the task itself was clear:

Sakishima Gunto had two major islands, Ishigaki and Miyako.

Each island had three established airfields.

These were to be kept out of action as much as possible.

Ishigaki Island:

Ishigaki Main (paved, 26 heavy and 66 light AA),

Miyara Field (grass)

Hegina Field (grass)

Miyako Island:

Hirara Main (paved, 12 heavy and 54 light AA),

Nobara Field (paved)

Sukuma Field (paved).

There also was a seaplane base at Karimata.

The British Fleet’s objective was to crater the runways and keep them inoperative while maintaining a fighter presence to destroy any aircraft detected in the air or on the ground.

To achieve this, Admiral Rawlings and his officers devised two plans which would apply when the circumstances suited:

Plan “Peter”: Applicable when little use was being made of Japanese airfields. The day was to start with a fighter sweep, with a small “Target Combat Air Patrol” (TarCAP) to be maintained over each island and small harassment raids were to be launched from the carriers at frequent intervals.

Plan “Queen”: To be put into action if the enemy were staging large numbers of aircraft through Sakishima Gunto. As with “Peter”, the day would start with a fighter sweep but larger bomber strikes with heavy escort would be sent out to prevent Japanese reinforcements making use of the airfields.

It was at this point – when it was clear that the British Pacific Fleet would be operating in concert with the US Fifth Fleet – that Task Force 113 adopted its American-allocated unit designation of Task Force 57. The Fleet Train - Task Force 112 - would keep its British designation.

Task Force 57 Order of Battle

The British fleet was equivalent to an under-strength US carrier task group.

1st Battle Squadron: HMS King George V (Fleet flagship), HMS Howe

1st Aircraft Carrier Squadron: HMS Indomitable (Flagship Aircraft Carriers), HMS Victorious, HMS Illustrious, HMS Indefatigable, HMS Formidable (still enroute)

4th Cruiser Squadron: HMS Swiftsure (Flagship Cruisers), HMNZS Gambia, HMS Black Prince, HMS Argonaut, HMS Euryalus (Flagship Rear Admiral Destroyers)

25th Destroyer Flotilla: HMS Grenville (Captain Destroyers), HMS Ulster, HMS Undine, HMS Urania, HMS Undaunted

4th Destroyer Flotilla: HMAS Quickmatch (Captain Destroyers), HMAS Quiberon, HMS Queenborough, HMS Quality

27th Destroyer Flotilla: HMS Whelp, HMS Wager

Whelp and Quality were replaced by Whirlwind and Kempenfelt after developing machinery defects

Air Groups

The British armoured carriers held about 220 aircraft between them. US aircraft made up 76 per cent of this force. A USN Fifth Fleet Task Group contained an average of 320.

HMS Indomitable: 857 squadron (15 Avengers), 1839, 1844 squadrons (29 Hellcats)

HMS Victorious: 849 squadron, (14 Avengers), 1834, 1836 squadrons (37 Corsairs), 2 Walrus ASR

HMS Indefatigable: 820 squadron (20 Avengers), 887, 894 squadrons (40 Seafires), 1770 squadron (9 Fireflies)

HMS Illustrious: 854 squadron (16 Avengers), 1830, 1833 squadrons, (36 Corsairs)

HMS Formidable: 848 squadron (19 Avengers), 1841, 1842 squadrons, (36 Corsairs)

Following United States Navy practice, the air group belonging to each carrier was given its own designation character (though, confusingly, the ships themselves had different characters).

The "X" designates this as a Corsair from Formidable.

BPF aircraft carrying the following letters on their tail can be identified as belonging to the following fleet carriers:

N = Implacable

P = Victorious

Q = Illustrious

S = Indefatigable

W = Indomitable

X = Formidable

The first digit of the three-digit aircraft identification number reveals how large the crew is (thus the two-seat FireFly's number always begins with "2").

Carrier deck characters were different to those on their aircraft. There is some suggestion this was a deliberate ploy to make Japanese pilots feel there were more aircraft carrier in the area, or at least to prevent them tracking particular aircraft types to particular ships.

The RN carrier codes also appear to have changed several times - at least for some ships. This was probably due to the potential to 'clash' with USN identification characters. The list below is not complete, but is as accurate as I can determine at this stage:

HMS Indomitable: N (Eastern Fleet), O (Sakishima Gunto)

HMS Illustrious: X (Sakishima Gunto?)

HMS Victorious: V (Eastern Fleet?), S (Sakishima Gunto)

HMS Formidable: R (Sakishima Gunto, Japan)

HMS Indefatigable: M (Sakishima Gunto?, Japan?)

HMS Implacable: F (Japan?)

* Indefatigable and Implacable have very poorly captioned pictures from 1945, one ship is often identified as the other.

USS Franklin burns after being hit by one, and possibly a second partially detonated, 250kg (500lb) bomb.

Vindication

The resolve of the US Pacific Fleet Admirals in retaining the British Fleet’s services was quickly vindicated.

Starting on March 18, the USN’s Task Force 58 – already at sea - would strike at the Japanese islands of Kyushu and Honshu in order to help isolate Okinawa.

The Japanese retaliation was severe: The carriers USS Enterprise, Yorktown, Wasp and Franklin here hit. USS Franklin lost almost 800 of her crew after fires raged through her open hangar, but the cripple managed to limp back to the United States.

The damage to these carriers was a major setback, imposing unexpected limitations on the USN’s planned operations.

Because of Admiral King’s reluctance, Task Force 57 would be two days behind schedule in joining its USN counterparts off Okinawa.

The British Pacific Fleet arrived at Ulithi where it topped up with fuel. It departed on March 23.