A Corsair lifts off from HMS ILLUSTRIOUS. Note the aircraft-handling vehicles and "Jumbo" crane parked alongside S1 pom pom in the foreground.

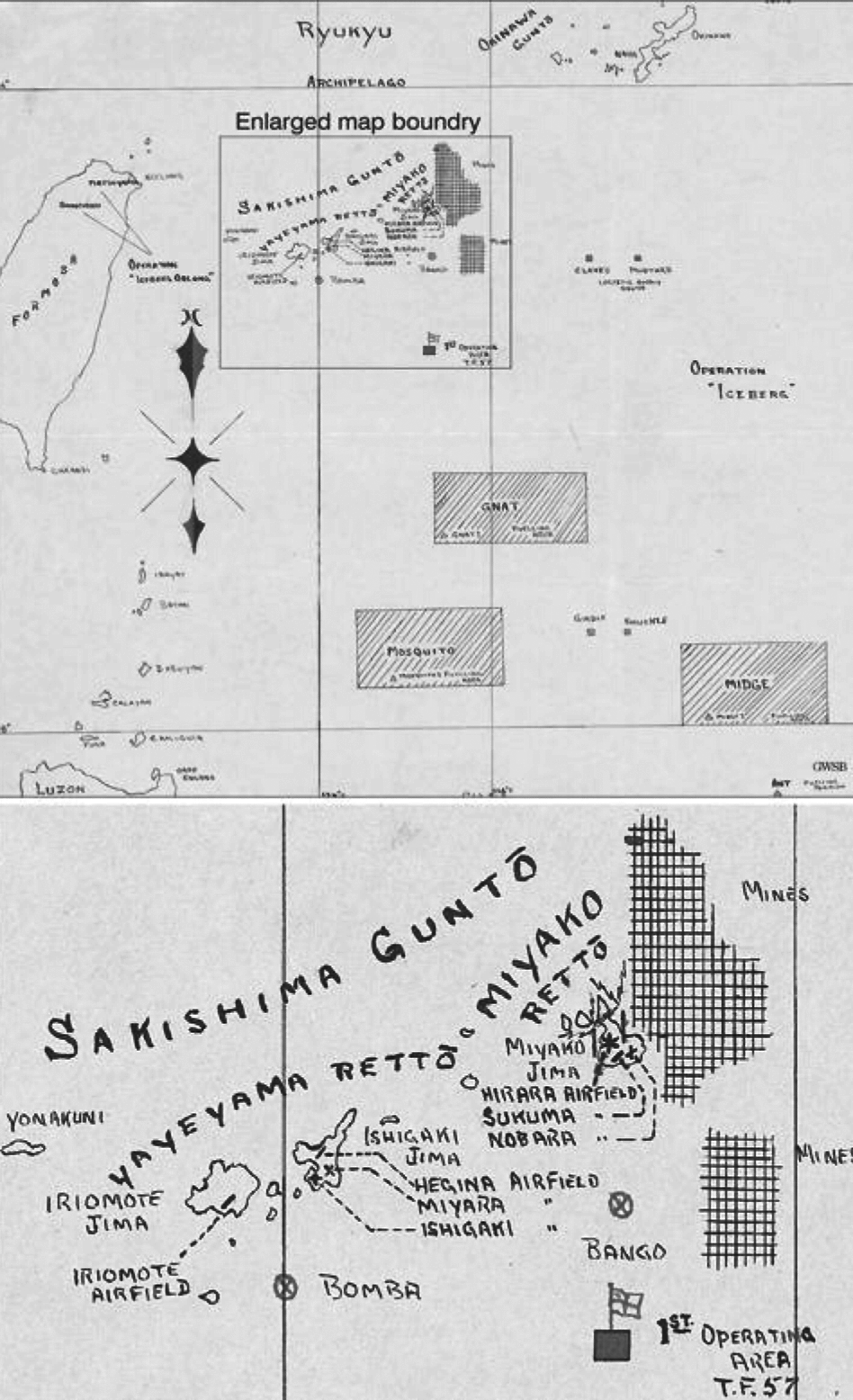

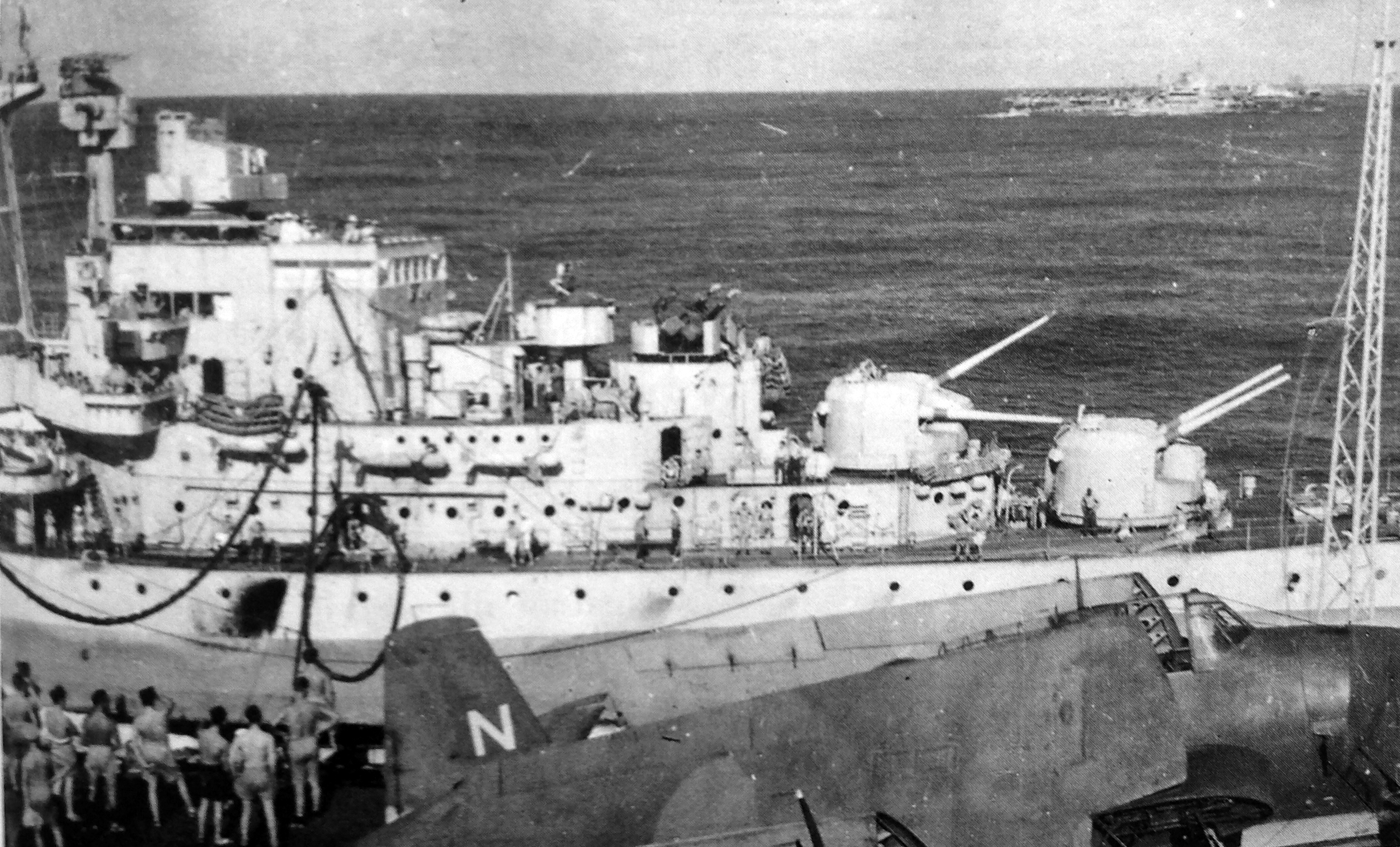

THE British Pacific Fleet wrestled with the difficulties of underway replenishment on March 25 when Task Force 57 rendezvoused with its tanker support group just outside the combat zone for the first time.

The escort carrier HMS Striker distributed four replacement aircraft among the fleet carriers and helped refuel the destroyers.

HMS Speaker provided CAP for the formation as the fleet carrier fighter pilots rested in anticipation of their coming days over Sakishima Gunto. Anti-submarine patrols, however, were maintained by the Avengers of the big carriers.

Low cloud spoiled much of the day’s planned anti-aircraft exercises, but a few ships managed to get some shots off at various drogues. The lack of discipline that had killed 11 in Illustrious only a few weeks earlier was once again evident. This time, several pom-pom rounds form the carrier Indomitable passed close by the battleship Howe. The captain apologised.

Shortly later Howe let fly with her own close-range armament, prompting this exchange of signals:

Indomitable to Howe:

ONE OF MY AIRCRAFT HANDLING PARTY WAS STRUCK PAINLESSLY ON THE BUTTOCK BY A FRAGMENT OF SHELL DURING SERIAL 5 STOP SUGGEST THIS CANCELS MY POM POM ASSAULT STOP

The battleship replied:

From Howe to Indomitable

YOUR 0950 STOP PLEASE CONVEY MY REGRETS TO THE RATING AND ASK HIM TO TURN THE OTHER CHEEK STOP

That evening, Rear Admiral Vian assumed tactical command of Task Force 57.

While aircraft were operating, the British carrier admiral was given tactical control of the fleet in order to ensure the carriers and their escort would synchronise their manoeuvres, such as turning into the wind to launch and recover aircraft, and into incoming suicide aircraft.

Before dawn the next day, Vian would manoeuvre the fleet to within 100 miles south of Miyako island in preparation for the first airstrikes.

March 26

As the sun rose, so did the dawn CAP and anti-submarine patrols.

At 0605 the fleet turned into the wind when 100 miles south of Miyako. The first fighters took took to the air at 0615. A short 30 minutes later, the lead RAMROD of fighters made a sweep over Ishigaki and Miyako’s Hirara and Nobara airfields. The 48-aircraft strong fighter flight was tasked to prevent Japanese fighters from rising to engage the bombers on their strike runs shortly after.

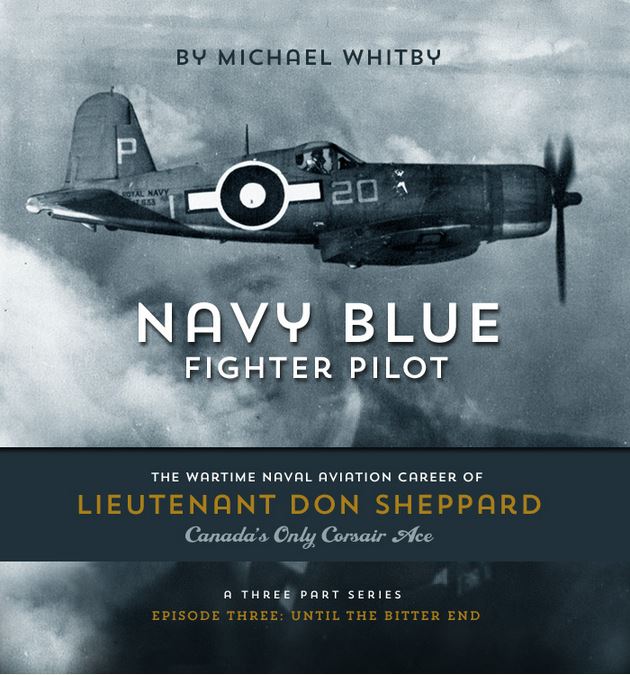

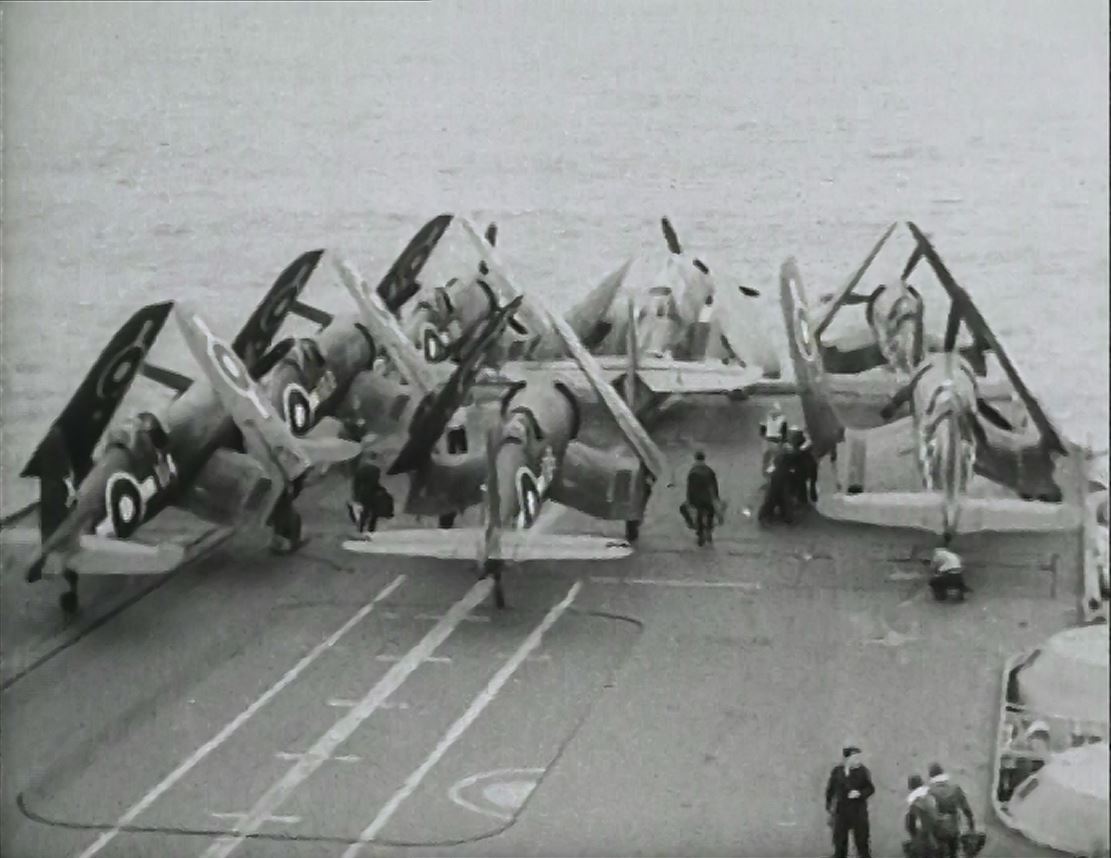

Victorious’s 1836 Corsairs were taking part in a RAMROD over Miyako.

Sub Lieutenant D.T. Chute, RNVR, wrote:

“A low level approach was made until nearing Miyako Jima when the sweep climbed up to 8000ft and swept round to an up-sun position of Hirara airfield. Drop tanks were released and Green Flight followed Red Flight in a steep diving attack on the airfield from the north-east, opening fire at long range and closing to zero feet where it could be seen that the targets attacked were either dummies or damaged aircraft.”

At 0940, Seafires from the fleet’s CAP were vectored on to a Dinah reconnaissance aircraft. It was heard making a sighting report as it passed overhead, but managed to escape at high speed.

A strike of Corsairs and Avengers is launched from HMS FORMIDABLE.

Back on board HMS Victorious, briefing officers detailed the day’s targets: Strike Baker would be made up of 15 Corsairs which would contribute to attacks on barracks at the northern end of Miyako, a radio station south-east of Hirara and Hirara airfield’s infrastructure. Other targets would include Nobara airfield’s barracks and a factory at Tomari.

Strike Charlie would be made up of six Avengers and 12 Corsairs. These would join other Avenger squadrons from the fleet to focus on the airfields at Hirara and Ishigaki some two-and-a-half hours after Baker had been completed. Their escort was a flight of fighter-bomber configured Hellcats divided between top, middle and close escort groups.

This, the first big raid of the day, involved over 40 aircraft. The six Avengers from Victorious joined the strike at 0920, each armed with four 500lb MC bombs.

One Avenger crew member quipped:

“We would have been better off using three-cornered tin tacks instead of bombs designed to sink the Tirpitz; they just went in – made a small hole and the Japs filled them in again that night.”

Heavy and accurate flack rose from the airfields and brought down an Avenger of 854 Squadron over Ishigaki. An escorting Corsair was also hit and seen to ditch, taking its pilot down with it. This was piloted by the commanding officer of Victorious’ 1836 Squadron. Commander C.C. Tomkinson who did not survive.

HMS Victorious’ Captain Denny would report:

The loss of Lieutenant Commander (A) Tomkinson RNVR is thought to have been caused by a faulty life jacket. He was observed in his life jacket in sight of land and the position was accurately fixed. Sub Lieutenant (A) Rhodes saw him in the sea and took part in the search.

Deck handling crew mill about aboard HMS IMPLACABLE, with a folded FireFly sitting on the dual-track catapult.

Another Corsair ditched some 20 miles off Tarima Shima island. This pilot was plucked from the sea by one of the Walrus rescue aircraft ‘before he had time to get his feet wet’.

Several false “bogeys” had already been intercepted. USN anti-submarine Liberators had been operating in the area without their IFF turned on. CAP fighters were directed towards all contacts and forced to visually identify each target before taking position for an attack run.

A Task Force 57 destroyer opened fire under radar control on one such unidentified approaching aircraft before a “friendly” warning was given. It was a USN ASR Liberator.

The FAA claimed 23 Japanese aircraft destroyed on the ground. Photo-reconnaissance would later amend this to only 12 real aircraft, with only one aircraft destroyed. The remainder were assessed as dummies or duds.

Four FAA aircraft had been lost in action and another five in accidents.

HMS VICTORIOUS launches aircraft. The low freeboard betrays this as one of the original three Illustrious class carriers, while the clearly silhouetted director in front of the island is a modification made to HMS VICTORIOUS and FORMIDABLE before the Sakishima operation. The position of the radar mast reveals this to be VICTORIOUS.

March 27

At 0245 HMS Indomitable detected a bogey approaching from the east on her SM-1 radar. The night was calm with a bright moon, so the decision was taken to send up a single Hellcat with an experienced pilot in an attempt to intercept.

Admiral Rawlings ordered the BPF to alter course.

Shortly after 3am, threat warning receivers on Task Force 57’s warships lit up as surface-search radar from the Japanese aircraft washed over the fleet. The cruisers and battleships engaged their jamming equipment, but the Japanese aircraft changed course to match that of the ships.

The anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Euryalus moved out from the fleet towards the shadower and opened fire by radar control at extreme range.

Indomitable’s Hellcat pilot of 1839 Squadron had managed to close with the bogey by moonlight – only to have his attack run spoiled by cloud at the very last moment.Unfortunately for the Hellcat pilot, the reconnaissance aircraft had actually spotted the fighter as it approached. It had evaded by diving into cloud.

About the same time an unidentified aircraft had attempted to contact the Hellcat, “warning” him that he was approaching an American. This was to prove to be a common tactic of the Japanese throughout the campaign.

This failed interception was to have an unexpected benefit: It convinced the Japanese that the British had night-flying capability and no further night engagements were attempted.

A RAMROD of 24 Hellcats and Corsairs was launched against the Sakishima islands at daybreak. Two strikes, each of 24 Avengers, were also dispatched, along with four Fireflies armed with rockets. These bombed and strafed Sukama airfield, harbours and shipping around the islands, as well as the radio transmission facilities at Hirara .

No Japanese aircraft were encountered.

However, a Corsair of 1834 Squadron was shot down by flak.

THE RESCUE OF LT CDR NOTTINGHAM

Norman Hanson, conversation with John Winton.“At about 5.45 I said to the CO of the submarine that I would definitely have to go at six, because I had no earthly idea how far we had to fly. The fleet were headed out to the replenishment area by this time. I certainly didn’t want to risk a night landing with my boys. We were no night landers in Corsairs. He said, “one more search”. I said, “It’ll have to be just one, and we’ll make an all-out effort, just one fighter to stay with you, the rest will go and search”. I was worried because it was getting duskish and I didn’t like my boys floating out there on their own, on an open sea with no other ships. The other three went off and I stayed with the submarine. They’d just gone when, suddenly, way down on the starboard side, I saw a flare come up, about a mile and a half to the south of us. The submarine saw it at the same time and it turned on a sixpence. I recalled the boys and screamed off down and there was old Frieddie, sitting in his dinghy, waving his paddle furiously at me as I went over. The submarine came tearing down and – terribly efficient – long before she got to Freddie she had a couple of lads in bathing trunks with life-lines round them out on the hull. Immediately they drew up alongside Freddie and the two lads jumped into the water and helped him up on to the pressure hull.”

Sub Lieutenant S Leonard, RNVR, of Victorious was leading strike “Dog” in the attack on Hirara Airfield:

“I strafed dummy aircraft and AA positions. Sub Lieutenant Spreckly from Victorious was flying on my port side, in line abreast, and was apparently hit by AA fire. He nosed over from 50 feet, hit the ground and exploded. After the first few days the Jap gunners stopped using tracer bullets and as we couldn’t see them firing, up went our casualties.”

An Avenger is wheeled into the forward deck park, probably aboard HMS FORMIDABLE

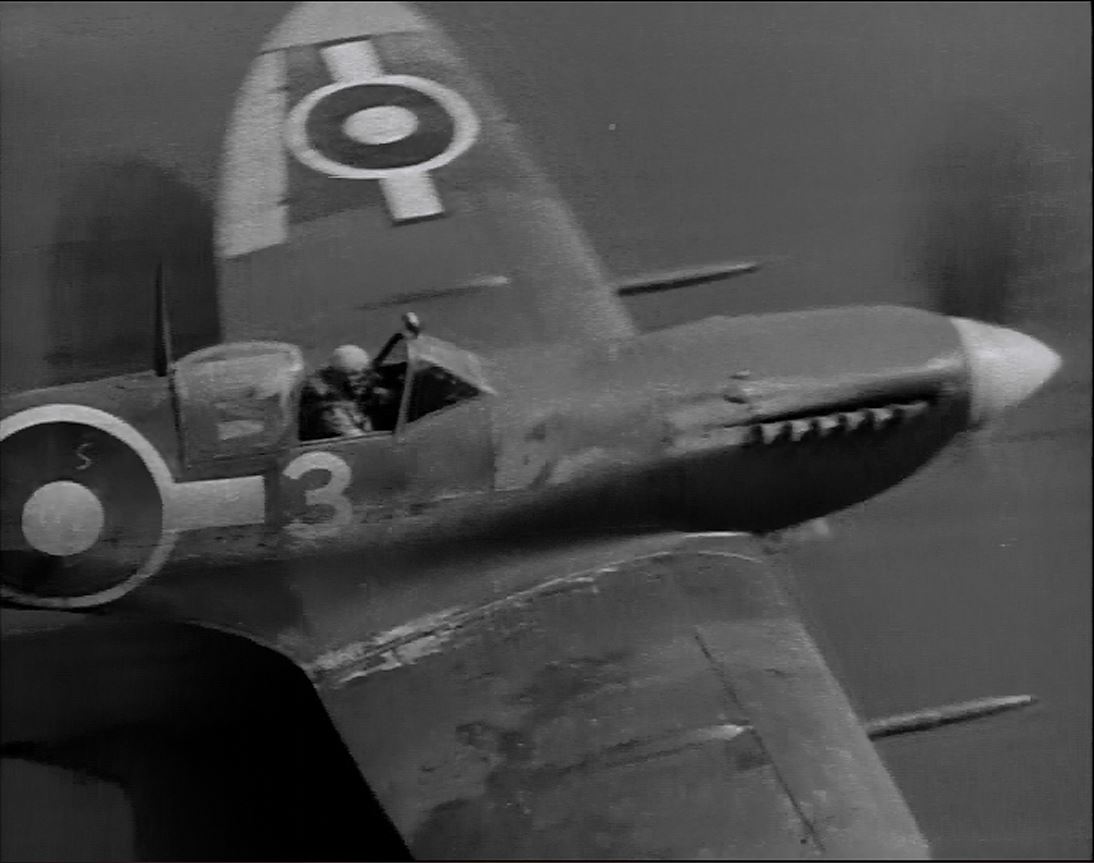

An FAA Corsair wearing Pacific Fleet livery.

Another of the lost aircraft was an Avenger of 854 Squadron piloted by their new CO - Lieutenant Commander Nottingham from South Africa. The aircraft was hit in the starboard wing, which caught fire, while over Hirara. After jettisoning bombs and struggled out to sea, Nottingham set the vibrating bomber into a dive in an effort to extinguish the fires with the slipstream. The wing, however, broke off. Only the pilot was able to bale out.

A Corsar on its take-off run aboard HMS ILLUSTRIOUS.

An Avenger from Indomitable spotted the dingy which was sitting just outside the designated submarine rescue zone. The US submarine Kingfish had to “ask her boss first” before moving out of her patrol area. This would prompt a clash between Vice-Admiral Vian and his American Liaison Officer who refused to order the submarine to break its operational orders. Vian appealed direct to Admiral Spruance for assistance, who immediately complied.

There was some serendipity in this help: HMS Undine had been dispatched to help rescue an FAA Corsair pilot, a Strike Leader, who had ditched some 50 miles from the fleet. Undine found the hapless FAA pilot – as well as a USN fighter pilot. He had been shot down off Okinawa three days earlier and had been bobbing among the waves ever since.

A patrol of four of Illustrious’ Corsairs kept a watchful eye out as the USS Kingfish nosed its way out of its comfort zone and engaged in a three-hour search for the downed FAA pilot. Just as the Corsairs were about to withdraw in the growing gloom after 1840, a red flare was spotted low on the horizon. Nottingham had waited until night before using the three small flares strapped in his survival pack. The fighters remained overhead as the USS Kingfish raced to pull the commander out of the water.

Two FAA aircraft had been lost in combat while a further six were claimed by accidents. Two further pilots died when their Seafire’s crashed while attempting to land on HMS Indefatigable.

With a typhoon warning issued by Guam, Admiral Rawlings abandoned his plans for another round of strikes – and a big gun bombardment of the island - on the 28th and instead ordered an early replenishment.

This would ensure TF57 would be in the operational area on April 1: The three day period during which the landing operations would commence on Okinawa would be when Admiral Spruance would need the BPF’s support the most.

March 28, 29 & 30

TF57 arrived at Support Area Midge, making the rendezvous at 0730 on March 28 and immediately began refuelling and reprovisioning. An almost never-ending litany of errors, breakages and breakdowns would keep the fleet hard at it for the full duration of the resupply period.

Destroyers Quality and Whelp re-joined the task force while Kempenfelt and Whirlwind, which had been their replacements, returned to the Fleet Train screen. Seventeen replacement aircraft were flown off to the fleet carriers from HMS Striker.

CAP was also supplied by Striker’s Hellcats – though each of the four fleet carriers held four fighters on their deck ready for an emergency launch.

A FireFly from HMS INDEFATIGABLE displays flak damage to its right wing as it is manhandled towards the forward deck park by landing parties.

March 31

Task Force 57 returned to the islands of Sakishima Gunto, this time deploying a cruiser and destroyer some 30 miles away from the fleet on a bearing of 300 degrees. Acting as a radar picket, the cruiser was used to assess returning strike formations for Japanese kamikaze or reconnaissance aircraft attempting to hide among their numbers.

All aircraft had to be visually identified before they were allowed to continue on to the home fleet. Several CAP fighters were assigned to this cruiser and served the important secondary role of helping to guide damaged or distressed aircraft back towards the carriers, or towards the rescue submarine.

A TarCAP was constantly maintained over the islands during daylight hours to suppress enemy flight operations while a separate formation of Seafires was held over the fleet. The first fighter sweep of eight Hellcats and 16 Corsairs overflew Miyako and Ishigaki, reporting only moderate activity on the airfields below.

Plan “Peter” was initiated and groups of four fighters were sent to each island in succession to maintain a presence during the whole day. Some of these fighters carried bombs which were dropped en-route to their CAP stations.

Two bombers strikes of 11 Avengers each were flown off at 1215 and 1515, with fighter escort, to pound Ishigaki airfield. No Japanese fighters were seen in the air and the airfield was heavily cratered.

Six Avengers from HMS Victorious’ 849 Squadron took part in the 1215 raid. After climbing to 10,000 feet, the Avengers joined the formation headed for Ishigaki. Hits were reported on the airstrip, barracks and radio station.

A DESTROYER AND AIRCRAFT CARRIER AT WAR

Jack TaylorDawn had broken and the sun was coming up on the horizon. Daylight came very fast. “Starboard watch to breakfast! Port watch stand fast!” 30 minutes later “Starboard watch close up! Port watch to breakfast!” By 0700 hours we were all back at Action Stations. From the three carriers there were some 80 aircraft in the attack on Sakashima for this was where the Japs had come from when they attacked us. 1000 hours “Alert! Alert stand by to take on aircraft.” Our lads were returning. We had mustered 25 aircraft and now the count started. Some were trailing smoke, some blowing oil and others with pieces shot out and full of holes. In came Lieutenant Churchill with a great deck landing and oil blowing back over “Veronica.” The handlers quickly pushed the plane into the cleared area to allow others to land on. Churchill was yelling, “Change that oil line and armour up! Refuel!” He was in one big hurry to get back again.

Unfortunately Roberts did not come back. All tolled we lost 5 planes. Three of the pilots managed to radio that they were ditching and gave us a position. A destroyer was sent to pick them up out of the sea.

Number 6 Avenger of 849 Squadron was hit during the run in and observed to crash on the runway after making his attack. Strike leader Lt-Cdr Stuart was forced to ditch his Avenger after taking damage from flak. USS Kingfisher once again plucked the three men from the water. Another two aircraft were lost through accidents.

As the fleet withdrew to the south for the night, Indomitable prepared two Hellcats on deck ready for any further night interceptions. The Hellcat, with its shorter nose, was regarded as being much easier to land at night than the Seafire or Corsair. No “snoopers’ were detected, however.

.A Seafire is pushed into position as a strike of the light fighter and Avengers if formed aboard HMS IMPLACABLE.

April 1

It was April 1 – Easter Sunday – when the British Pacific Fleet encountered its first Japanese strike.

The tempo had well and truly been upped. The landings by United States troops had begun that morning on Okinawa.

By 0643 the first of the RAMRODS were on their way to the Sakishima islands. HMS Argonaut and Wager took up their “de-lousing” radar picket duty.

At 0650, barely 10 minutes after the RAMROD had headed towards Ishigaki, a large Japanese formation was detected approaching Task Force 57 from some 75 miles to the west at 8000ft. It was a group of about 20 aircraft from the Japanese First Air Fleet based in Formosa.

Standby CAP fighters were launched and the RAMROD Corsairs and Hellcats were recalled. The Fighter Control Officers directed them all towards the enemy contacts which were approaching the fleet at about 210 knots.

The raid, by now judged to be about 15 aircraft, split up when about 40 miles from the fleet.

At this point a flight of Victorious’ Corsairs made the first interception, a kamikaze flying either an Oscar or a Zeke. It was sent spinning into the sea. Lt Cdr Tommy Harrington recalled:

“He was flying out of killing range and I carefully fired a good long blast over his port wing. He very kindly obliged by executing rather a difficult turn to port, which enabled me to close and shoot this unhappy amateur down”

The Hellcats and Corsairs from the returning RAMROD were soon to claim three more. Another of Victorious Corsair pilots, Lieutenant D.T. Chute, was among the RAMROD fighters:

“The squadrons had reached a height of 15,000ft heading for the islands when we were given a vector for the bogeys heading towards the Fleet. The first height given was 12,000ft but later changed to 19000ft and all squadrons climbed. The bogeys were next detected at sea level and down we went.”

The bulk of the raiding force broke through the RAMROD fighters and raced towards the Task Force. The ships were called to “Flash Red” alert.

Lt Cr Foster: Operation Iceberg II

Strike “Baker”, 1st April 1945Report of Commanding Officer, No. 849 Squadron – Strike Leader

1220 Airborne (2nd TBR Victorious)1227 Victorious group formed up;1239 Strike took departure1241 Commenced climb1313 Landfall Ishigaki1315 Attacked Ishigaki Airfield1327 Left R/V for base1410 Sighted Fleet

The forming-up was good, although three flights took part instead of only two. There were no incidents on the way to the target. R/T discipline was good, although there was a lot of interference on Button B, which may have been enemy jamming.

Landfall was made at the S.E. of Ishigaki, which was moderately clear of cloud. The flights were deployed to starboard, and the attack made from the East, working round to the North. Flak was again light. Fighters were not sent down, as there did not seem to be any serviceable enemy aircraft in the dispersals. The primary target for all three flights was the runway and the taxi tracks leading to it. The bombing was good. Four sticks were definitely seen to burst on the runway, while the control tower was hit by at least one stick. The administration buildings, south of the airfield, were not left undisturbed.

The return journey was without incident

Remarks: The one or two carriers, of which Victorious was not one, who flashed their identity letters to approaching strikes are a great help; the sooner they flash the more it helps. It gives the Strike Leader a chance to manoeuvre his strike, so that individual flights or squadrons can get to their waiting positions quickly and without confusion. It also lets him know that the strike has been recognised as friendly.

One fighter – conflictingly reported as a Zeke or Oscar - made a dash at wavetop height, chased by several fighters.

At 0725 it strafed Indomitable’s flight deck from stern to stem, killing one and wounding six. It then turned its guns, without effect, on the battleship HMS King George V.

Three minutes later, another Zeke would slam into the base of Indefatigable’s island.

Seafire pilot S/Lt R. H. Reynolds had engaged the Zeke in its death-dive and reported hitting it repeatedly at long range, including on the wing root. He had to pull up sharply to avoid hitting the carrier himself.

He was awarded a “shared kill” credit on the kamikaze.

Later, one 894 Squadron Seafire which had been diverted to Victorious while Indefatigable’s flight deck was unavailable, crashed on landing - killing its pilot.

At 0755, a Zeke – once again chased by S/Lt Reynolds in his Seafire - dropped a 500lb bomb close to the destroyer Ulster.

The near-miss collapsed the bulkhead between the rear boiler and engine rooms. It also split the ship’s hull. Two were killed in the engine-room, and one injured. Reynolds shot the offending Zeke down, and another which had come to its aid.

Out of ammunition, Reynolds was able to make a somewhat precarious landing on his home carrier - the Indefatigable, which had cleared its flight deck just in time.

WITNESS, ATTACK ON HMS INDEFATIGABLE, APRIL 1

S. Lt Ivor Morgan, pilot 894 squadronThen came the crash, followed immediately by flame and a searing heat. I choked. I could not draw breath. I believe I lost consciousness. I next remember opening my eyes to see all the recumbent forms near me. All immobile. All dead, I thought I must be dead too... ‘Port fifteen’.

The Captain’s voice brought us to our senses and we shambled rather sheepishly to our feet...

As soon as I was relieved, I went below to the hangar where maintenance crews were working with every sign of normality. They had thought their last moment had come when, unable to see what was happening, a terrible explosion occurred right above their heads. Flaming petrol ran down the hangar bulkhead, presumably through a fissure in the flight deck, threatening to engulf men and machines alike. Under the leadership of CPO ‘jimmy Green, Senior Air Artificer, the fire was brought under control without having to resort to sprinklers.

“Right lads. Show’s over. Back to work”...

Finally, ‘Guns’ (Tony Davis) requested over the Tannoy system that any bomb fragments he brought to him for identification in order that he might have some information on the type of missile being used by the enemy for this sort of attack. Among the pieces which were offered was the nose cone - in fact, that of a Royal Navy 15” shell, almost certainly captured at Singapore several years earlier!

A Seafire III lands aboard an unidentified carrier. The lighter tone of the aerilon and wingtip on the left wing is not a specific marking. Carrier mechanics say such miss-matched panels were simply spares which had not been painted to Pacific Fleet standards..

The cruiser Gambia took the motionless Ulster in tow once the raid was over. They would slowly make their way back to Leyte.

With Indefatigable back in action, a strike of 16 Avengers escorted by Corsairs was launched at 1215. The target was the airfields at Ishigaki.

Later, TarCAP aircraft reported activity at Hirara and Isigaki. A RAMROD was flown off and claimed three aircraft destroyed on the ground.A Corsair of 1834 Squadron was hit by flak and seen to make what appeared to be a perfect “ditching”. However, he was not found by the ASR Walrus or an extensive sea and air search.

At 1730 the fleet’s radar again detected incoming hostile aircraft, this time at low level.

The four suicide bombers from the Formosa-based 8th Air Division based at Schinchiku managed to sip past the CAP Hellcats in cloud. They were not spotted again until they came within sight of the fleet.

A single engine aircraft – it has not been established whether it was a Jill or a Zeke – made a dive on Victorious.

Good handling of the ship by Captain Denny saw the kamikaze strike a glancing blow when it touched a wing-tip to the flight deck before cartwheeling into the ocean where it exploded harmlessly.

The fleet then retired to the south-east to take up its night station.

The day’s FAA losses amounted to one aircraft in combat and three operationally.

Witness account: Waite Brooks, the British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George VI)

Suddenly, out of a cloud on our port quarter, a kamikaze dived straight for Victorious. We watched her guns go into action for the few seconds it took the kamikaze to bank across her stern and complete its dive for her flight deck. The wing hit the flight deck on the port side forward and the plane and its bomb exploded in the sea next to the hull. However, from our position on the ADP, we could not tell whether Victorious had been hit, or had a near miss. The plane appeared to hit her deck and a huge explosion followed. Her bow disappeared for about 30 seconds in a ball of black smoke, flying chunks of debris and an immense column of water. Our concern subsided as she reappeared and we received the report that her only damage consisted of a few bow plates that were strained by the force of the explosion. This event was barely a minute behind us, when Illustrious began firing at an aircraft diving at her. She shot it down very close to her port quarter. The next moment, another aircraft appeared off our starboard quarter. It was close and closing us rapidly, when one of our fighters dived at this kamikaze and shot it down. This was our last attacker, and we withdrew to the east in the fading light.

Witness account: Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard HMS King George V)

The “hands” bringing our breakfast from the galley were just emerging on the ADP red-faced and puffing after their long climb , when the ADR passed a bogey report from Indomitable. The bogey quickly became a group at 12,000 feet, 73 miles away. Our strike was only fifty miles from us and we were in position “Squeeze”, 70 miles south of the islands. The bogeys we held on our radar had to be Japanese. We had detected them over their airfields. Information about the raid developed rapidly. Radar estimated their numbers at 10 or 12 aircraft. The fighters on patrol were vectored to intercept them, and our fighter strike was diverted to help. At 47 miles, the fighters made contact and over the radio came the shout “Tally-ho!” as they merged with the Japanese on our radar screen. Dogfights were not the Japanese objective and out of the confused radar screen, one aircraft was detected 10 miles away, flying very low. It was a Zeke 32 and on closing the fleet, it climbed quickly into the bright, clear sky. All eyes stared into the dazzling blue , seconds passed, and suddenly there it was, almost over our heads in a steep dive heading straight for the Bridge/ ADP of KG V. It was already so close that I was looking directly into the engine of an aircraft whose pilot, I felt sure, was looking directly at me, standing in the centre of the ADP. Considering the speed and close range of this Zeke, all shouts of “alarm aircraft” and the furious efforts to bring the weapons to bear, had only seconds to save the situation . Each heavy anti-aircraft battery, the 5.25-inch guns, was controlled by a director, which had to locate the target, lock onto it-with their gunnery radar— and when a firing solution was reached, fire. This could be done quickly, but it was not a split-second operation. The close-range weapons were the closest we had to instant firing weapons, but even here, they had to spot the target, train onto it, and fire. In the majority of kamikaze attacks, the target had to be destroyed or the trajectory would carry the fuselage, with its engine, bomb and gasoline, to the target. The heavy anti-aircraft guns were the most effective weapon in this type of warfare.

A Seafire had spotted this Zeke and was closing it, but as yet had not engaged it. The kamikaze was seconds from crashing on the Bridge/ ADP section of the ship, when the “Good Lord,” perhaps for others, fate, stepped in, and the only thing that could save us from having this aircraft and its bomb right in our laps, happened. A few seconds from impact, the pilot made a sudden decision to change his target from us to the carrier beside us. The Zeke made a violent change of course without pulling out of its dive, flipped over , and hit Indefatigable’s flight deck at the base of the bridge superstructure. The damage and fire were controlled quickly and did not stop her from operating her aircraft, but three officers and 14 men were killed and more than 20 were wounded. On KG V, we had just had a close brush with a kamikaze that could have resulted in serious damage and casualties, in our opening battle of the Invasion of Okinawa. On the ADP we were not aware that when this Zeke was diving at us, it was firing its 20-mm cannons and machine -guns. Luckily, they missed the ADP, although some of the shots hit the deck below us. In the first moments of this Zeke’s attack, Indomitable was also strafed by it and was not so fortunate. She had several officers and men killed. This kamikaze was followed by another that dived at us, but while still quite high pulled out and was lost in the general melee going on in the air above us.

April 2

With the American beachhead on Okinawa now established, Admiral Rawlings cancelled a planned big-gun bombardment of Sakishima’s islands in anticipation of a surge of Japanese aircraft. He would write in the London Gazette of June 2, 1948:

“Once enemy aircraft begin staging through an aerodrome the most profitable means of destroying them is by air and not by guns.”

The morning was once again crisp and clear. Four Hellcats were launched at 0510 to chase down any Japanese aircraft operating in the dark from the Ishigaki and Miyako airfields. Two returned with radio failure, but the remaining two pressed on only to find no targets.

A RAMROD of 17 Corsairs and Hellcats was launched at 0630 to overfly the airfields. One Zeke was found over Ishigaki and shot down by FAA Hellcats. Two aircraft were claimed destroyed on the ground.

This was the only Japanese activity encountered that day. One FAA Corsair was seriously damaged. The pilot was rescued after he bailed out from his aircraft near the fleet.

At 1045 Task Force 57 withdrew towards resupply point Midge for another refuelling rendezvous with the tanker support group, handing over responsibility for containing the Sakishima Gunto to an escort carrier Task Force of the USN.

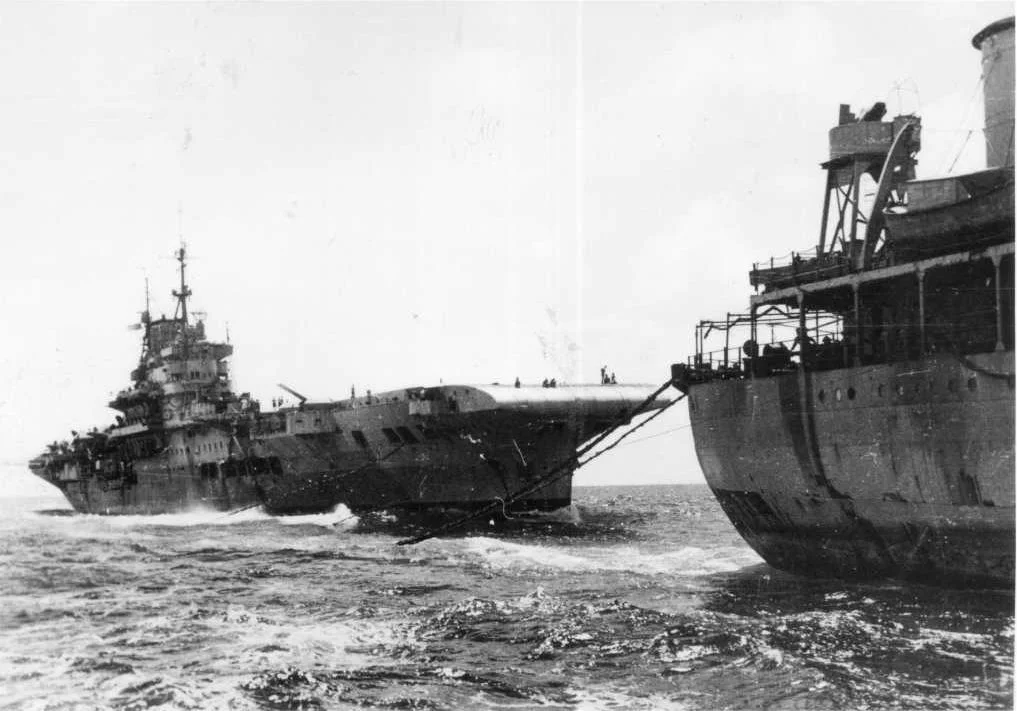

The oiler OLNA refuels HMS NEWFOUNDLAND with IMPLACABLE in the background.

April 3 - 5

Force 5 winds and a heavy swell forced Task Force 57 and the tankers to withdraw to another rendezvous point in the search for calmer weather. Refuelling and replenishment operations did not begin until April 4.

HMS Slinger flew off 22 replacement aircraft and received two flying “duds” for repair.

Refuelling in particular had been affected by the heavy weather, with considerable delays in rigging hoses and support lines. When the BPF set sail for Sakishima Gunto on April 5 at 1930, the battleships had only 50 per cent of their fuel oil capacity. The carriers had only taken aboard enough avgas for two days of normal operations.

One of HMS VICTORIOUS' Avengers ends up nose-first against the side of the carrier's island.

April 6

Task Force 57 steamed at 20 knots for most of the night to make up lost ground.

The flying program began on schedule.

At 0450 four Hellcats were flown off amid heavy cloud to reconnoitre Ishigaki and Miyako islands. They found eight aircraft on the ground at Ishigaki and engaged with strafing runs. One of these was claimed as destroyed.

A Hellcat of 1844 Squadron encountered a Frances twin-engined torpedo bomber on its return from Miyako later that morning. The bomber was shot down after a chase which covered some 30 miles.

At 0530 four Seafires lifted off to provide CAP for the radar picket ships, HMS Argonaut and Urania.

Then, at 0625, the Corsairs and the Seafires of the fleet CAP were dispatched, along with a few Avengers configured for anti-submarine patrol.

Finally, at 06.35, the Hellcats and Corsairs of the Tar CAP lifted off. The Avengers would follow shortly after.

In the worst traditions of the public service, the Avenger pilots would return to runways which had been repaired overnight.

Victorious’ Avengers were not to have a good day. The Squadron was to attack Hirara, but two of the six aircraft were unable to get of the carrier’s deck. The commanding officer of 849 Squadron found his Avenger to be inoperable, while another Avenger suffered a jammed brake on take-off which caused the aircraft to slew into the island. The Avenger was wrecked, but its crew escaped uninjured.

The remaining four of Victorious’ Avengers carried out the strike successfully and returned to their base ship at 1415.

Another Avenger, from 849 Squadron, ditched on takeoff.

The strikes that manage to get into the air in the early afternoon found the weather over the islands had deteriorated. They succeeded in hitting Hirara, Nobara, Sukhama and Miyara airstrips and barracks, and their fighter escort strafed radio and radar stations and three small boats. The cloud caused the returning aircraft to get separated, but all managed to return to their base ships without further incident.

Mainteanance crew examine an Avenger aboard HMS FORMIDABLE

Another kamikaze attack was launched on the Task Force as the sun dipped towards the horizon.

At 1655 the fleet’s radio frequencies were jammed. But the CAP, well directed by the fleet’s Fighter Controllers, was able to get in amongst the enemy aircraft early and shot down three Judy bombers. The outer picket of destroyers brought down a fourth.

But, five minutes after the initial contact, one Judy would plunge out of the clouds above the fleet.

HMS Illustrious threw her helm over hard but was clipped by a kamikaze which detonated in the sea alongside.

The carrier, while whip-lashed, appeared unaffected and no injuries were reported.

One of the Seafires of 894 Squadron which had attempted to follow the Judy into the fleet’s defence zone was shot down by friendly fire and the pilot killed.

The fleet’s radar sets began to fill with unidentified “blips” assembling around the fleet, and the fighter direction officers were kept busy attempting to organise intercepts.

A Jill was caught by one of Illustrious’ Corsairs. Another Judy was caught as it entered the flak barrage of the outer destroyer ring by a Hellcat and a Corsair.

An unidentified aircraft was seen to erupt into a fireball on the outskirts of the fleet. This kill would be credited to the 4th Destroyer Flotilla escorts.

Eyewitness account: Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George V).

It was always a nerve-racking game monitoring incoming information and searching the sky overhead. Our present situation was no different than most others , when our concentration was broken by several destroyers on the screen firing at an aircraft flying very fast just over the waves. Corsairs of our CAP rushed in and the Jap dropped his bomb to lighten himself in an attempt to escape. There was a large explosion and we strained to see what had happened . By the time the report came in, the intruder had been shot down. A moment later, another aircraft plunged out of the low cloud straight for Illustrious. It happened so quickly and the aircraft was so close, that not much could be done to destroy or avoid this kamikaze. It seemed certain that this plane and its bomb would strike Illustrious amidships. There was a violent explosion, and flying debris mixed with a column of water shot in the air as the kamikaze hit the sea just abeam of her bridge. The admiral signalled Illustrious asking if she had suffered any casualties. Her reply was, “No, but his wing tip hit my bridge!” A “Judy,” a Japanese navy bomber, attacked Indomitable and was shot down by a Hellcat no more than 50 yards from the ship.

April 7

For the BPF, the day the Japanese “super battleship” was sunk was just another day of routine.

Admiral Rawlings was aware of the low aviation fuel stocks aboard his carriers, so he once again considered detaching Task Force 57’s big guns to bombard the airfields in the place of air strikes.

However, reports from the USN were disturbing.

News had arrived from CinCPAC of the previous day’s Kikusui massed kamikaze attack, along with warnings of expectations of another.

Rawlings changed his mind: He kept the battleships and cruisers tightly clustered around the carriers.

Three strikes were launched against Ishigaki, Hirar and Nobara to yet again crater the airfields the Japanese had diligently filled overnight.

During a RAMROD operation a Corsair of 1830 Squadron drifted a little too high above the buildings of Hirara while in a strafing run. A Japanese round went through the front windscreen and was seen to decapitate the pilot before the Corsair plunged into the ground.

Ishigaki, Hirara and Nobara airfields were all hit. The London Gazette reports:

“All runways in the islands were left well cratered and unserviceable. All visible aircraft had been attacked and there was no activity on any airfield”.

The failure of an oxygen tank is believed to have caused the loss of a pilot of 1836 Squadron. Fellow CAP pilots reported the pilot had appeared to become disoriented before ditching.

A US ASR Privateer spotted the pilot in the water and dropped dinghies, loitering on station before several Fireflies took over the role. HMS Urania arrived at the scene to find the pilot inexplicably dead.

Two FAA Avengers were shot down over the airfields and four Corsairs were lost to accidents or mechanical failure. Three Japanese aircraft were claimed destroyed on the ground.

That evening, as Task Force 57 withdrew towards supply point Cootie, it learned of the Yamato’s futile final fling. When reading a report of the engagement, Rawlings commented:

“(It) filled the BPF with admiration and, at the same time, it must be admitted, with envy.”

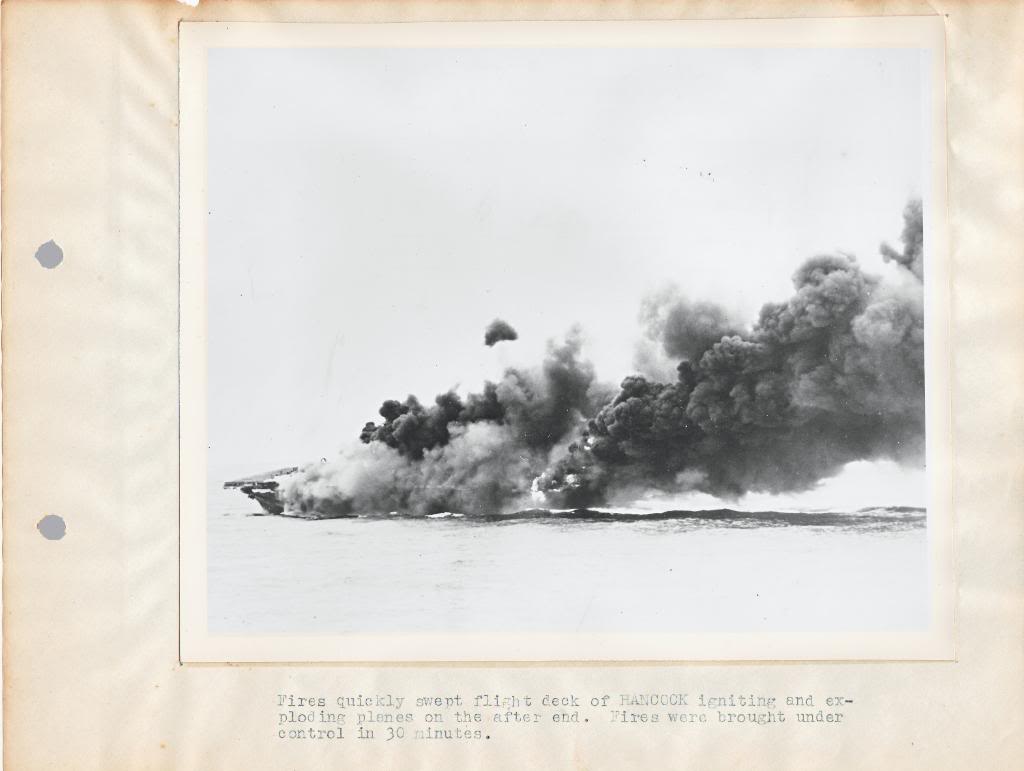

Less inspiring was news of a massed kamikaze raid against the USN which had caused the loss of the destroyers USS Bush and Calhoun, and the disabling of 21 further vessels including the carrier USS Hancock.

The Japanese had reportedly lost 380 machines in the effort.

The escort carriers of USN’s Task Force 52 once again stepped up to the plate at Sakishima as the British refuelled.

April 8 & 9

Practice at underway replenishment was beginning to have an effect, and this rendezvous was conducted with fewer incidents and a much faster transfer rate. Three flyable duds were delivered to the escort carriers in return for 13 replacement aircraft.

However, HMS Illustrious was to prove a cause for some concern.

While the kamikaze strike the day before had appeared to do little damage, it was becoming obvious the carrier was suffering severe vibrations.

It was believed the blast had unsettled the carrier’s old wounds. Underwater structural damage was now suspected.

With only two of her three screws operational, Illustrious had been steaming almost continuously at maximum power to keep up with the remainder of the Task Force.

RNZS Gambia re-joined the Task Force, along with the Canadian cruiser Uganda and the destroyers HMS Urchin and Ursa.

Once the RAS was completed at 1530 on April 9, the task force set sail for Sakishima Gunto for its final two day deployment before a scheduled return to Leyte Gulf.

Rawlings also heard that the USS Hancock, hit the previous day by a kamikaze and limping back towards Ulithi, had been so extensively damaged that she would have to return to the United States for repairs.

Royal Fleet Auxiliary Empire Salvage refuels HMS Whirlwind and HMS Illustrious. Note the unoccupied "outrigger" pylon between the Pom Pom mounts and the 4.5in turrets.

Redeployment

Admiral Spruance believed the most effective kamikaze units and most experienced combat pilots his fleet had faced so far were based out of Formosa. His fleet was already short of operational carriers and the soldiers on Okinawa and their supporting logistics ships needed constant air support. He was also concerned of the risk of sending his vulnerable flat-tops “into the lion’s mouth” of a close-range strike against the Formosa airfields.

But Admirals Spruance and Nimitz had been impressed by reports of the British armoured carriers’ ability to shrug off the kamikaze strikes of April 1. So the US Admirals came to their conclusion: The armoured British carriers would be deployed because they would be less vulnerable to counter-attack.

Corsairs and Avengers are stowed forward as a strike returns to the deck of HMS FORMIDABLE.

On April 9, Rawlings received a signal from Admirals Spruance and Nimitz to cancel operations against Sakishima Gunto. Instead, they “requested” that the next two-day strike period be against specific airfields in Formosa.

Shinchiku and Matsuyama had been identified as the source of several large kamikaze raids. They had to be neutralised.

The role of suppressing these airfields had previously been tasked to General MacArthur’s South-west Pacific Air Force. The moody General had shown little interest in carrying out this responsibility and only a very few raids had been conducted.

Admiral Rawlings, however, immediately seized on the opportunity.

Not only would it break the monotony of the routine already established at Sakishima, it would give the British Pacific Fleet the opportunity to demonstrate both its strength and adaptability.

The new operation was to be called ICEBERG-OOLONG.

What Admiral Nimitz had argued to Admiral King to be his “most flexible reserve” was now to be unleashed. Task Force 57 immediately changed course.

The extra day of travel provided more time for the weary maintenance crews to prepare the maximum number of aircraft for the strikes, and for their pilots to grab as much sleep as possible.