With Britain's unique challenges established, an answer had to be found. Armour was deemed the best middle ground.

“Whatever the truth is, both the Americans and the Japanese paid the Illustrious design the compliment of copying its main feature. Since 1944-45 all large US carriers have incorporated armoured flight decks. During the late stages of World War II it was suggested that the Royal Navy should hand over all six of the Illustrious type in exchange for six Essex class. This interesting mutual abandonment of cherished principles never took place, but it testifies to the merits of the British design.”

The Royal Navy of the 1930s resolved to build a carrier not merely capable of surviving sustained air attacks, but of continuing air operations after taking a measure of battle damage.

Such a carrier needed to be able to protect its aircraft, to provide fleet reconnaissance and trade protection, as well as offer air patrol and combat strike functions.

The challenge was to provide this within restrictions defined by treaty limits.

This was achieved by an ingenious – and for some considerable time Top Secret - design which incorporated an “armoured box” hangar into a strength deck that was also the flight deck.

It was an innovation which provided considerable weight savings for such a heavily armoured structure. But it came with a cost.

The history of the Illustrious design as far as I am concerned was that I formed a committee of the brightest naval officers at the Admiralty to study the Navy of the future.

We were in a fury because we thought we were building the Navy of the past instead of the Navy of the future. Our idea was that the carrier was the prime fighting ship.

In all this the Constructors were most sympathetic and helpful. The Controller Henderson was not.

To maintain stability under the strict treaty weight limitations, the second hangar that Ark Royal had featured would have to be discarded. As a result, the Illustrious Class would be limited to 33 internal stowage stations for aircraft.

“Weight economy was vital, both to comply with the Treaty and to help stability and the armour was worked structurally. The main deck beams were 6ft deep but, even so, Forbes was to quote a leading structural expert as saying that he would have used twice as much material. The structural design was a magnificent feat of engineering, reflecting great credit on the assistants, Sherwin and Stevens.”

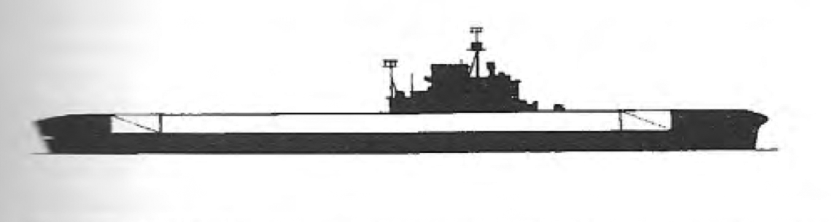

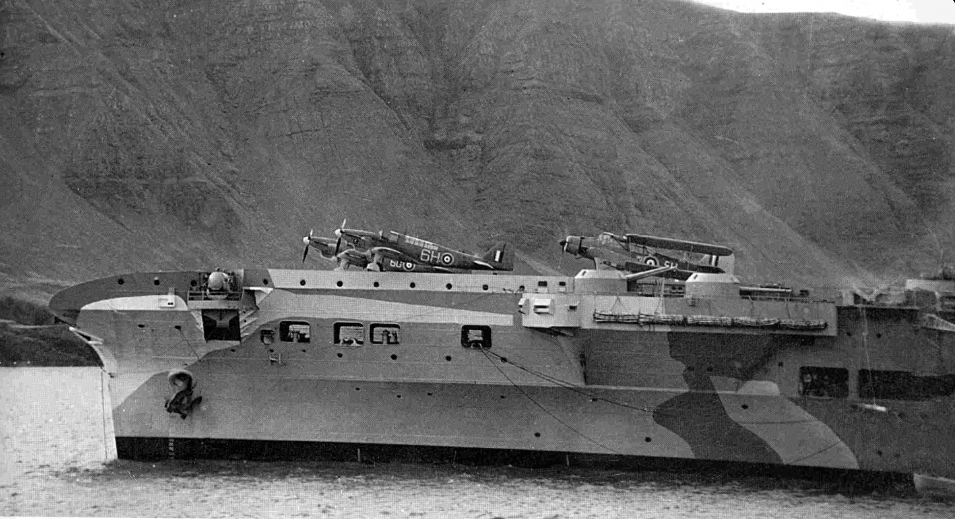

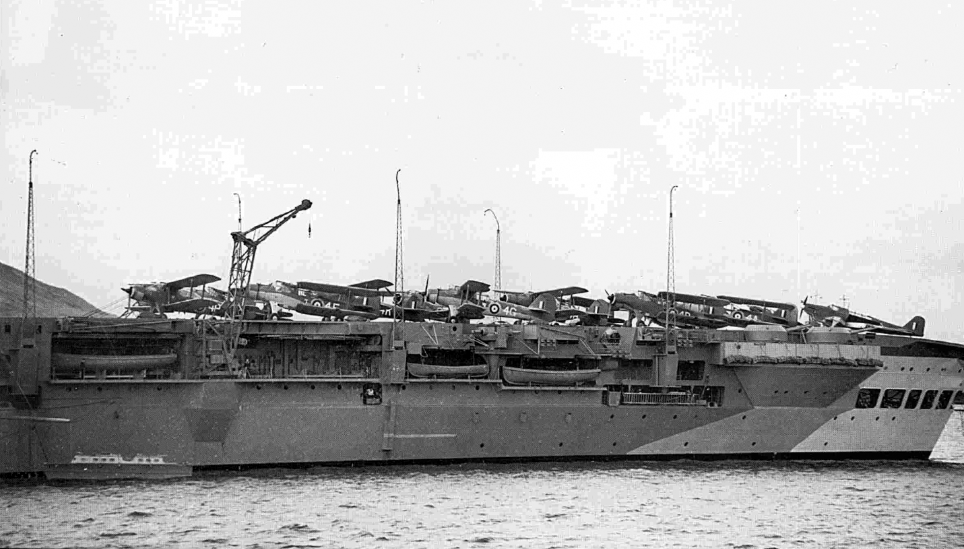

HMS ILLUSTRIOUS in her original 1940 overall grey guise, starboard profile.

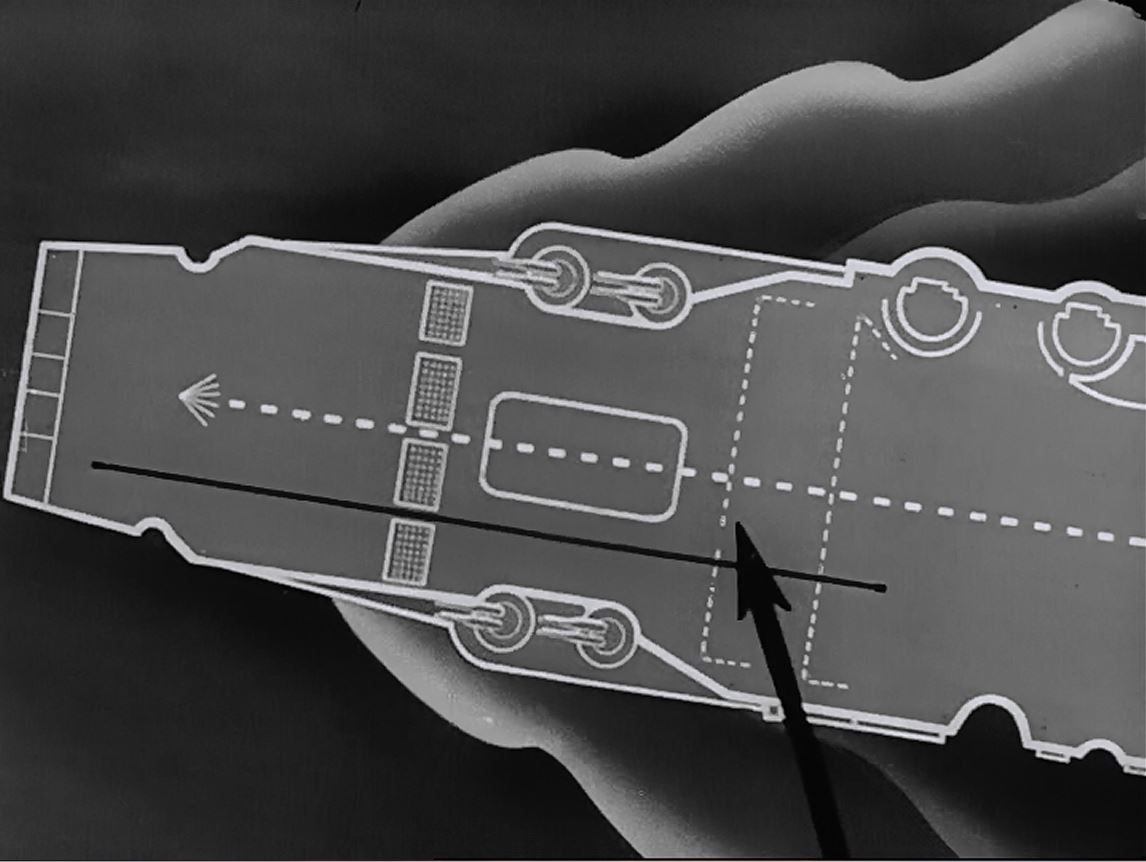

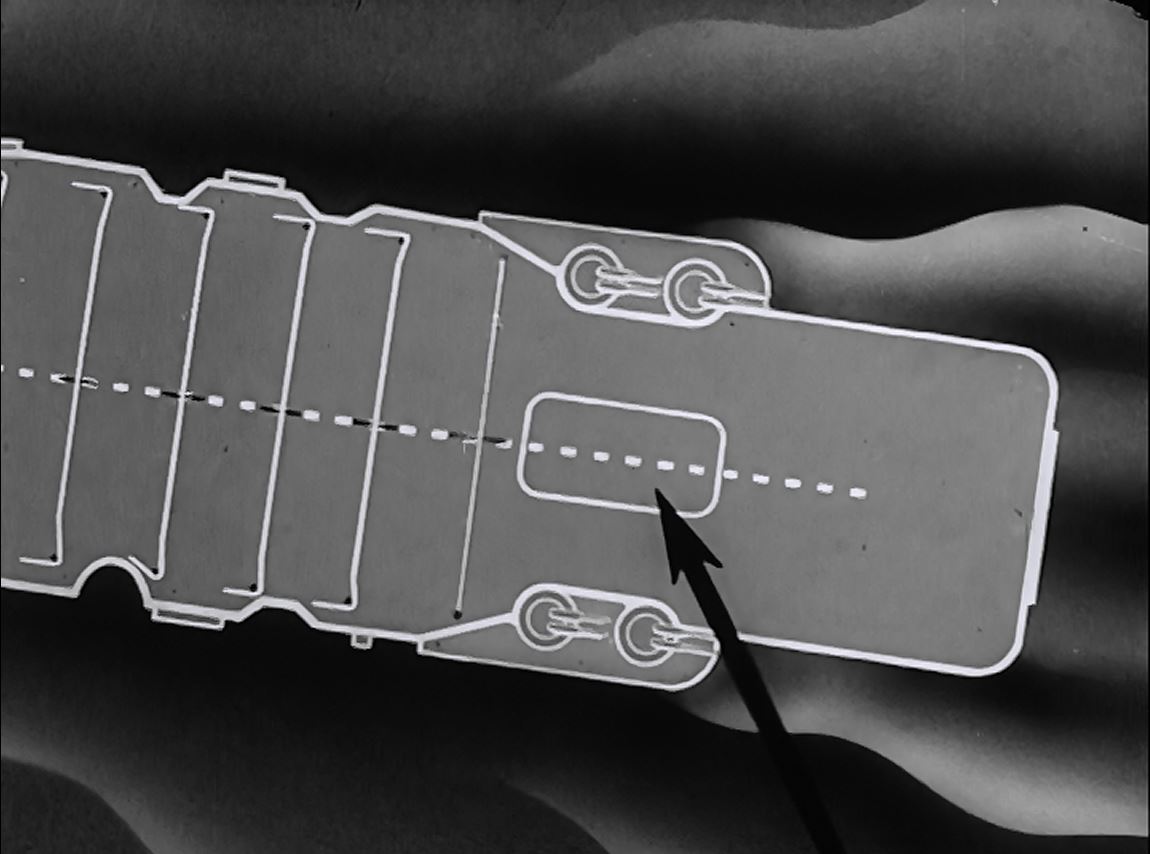

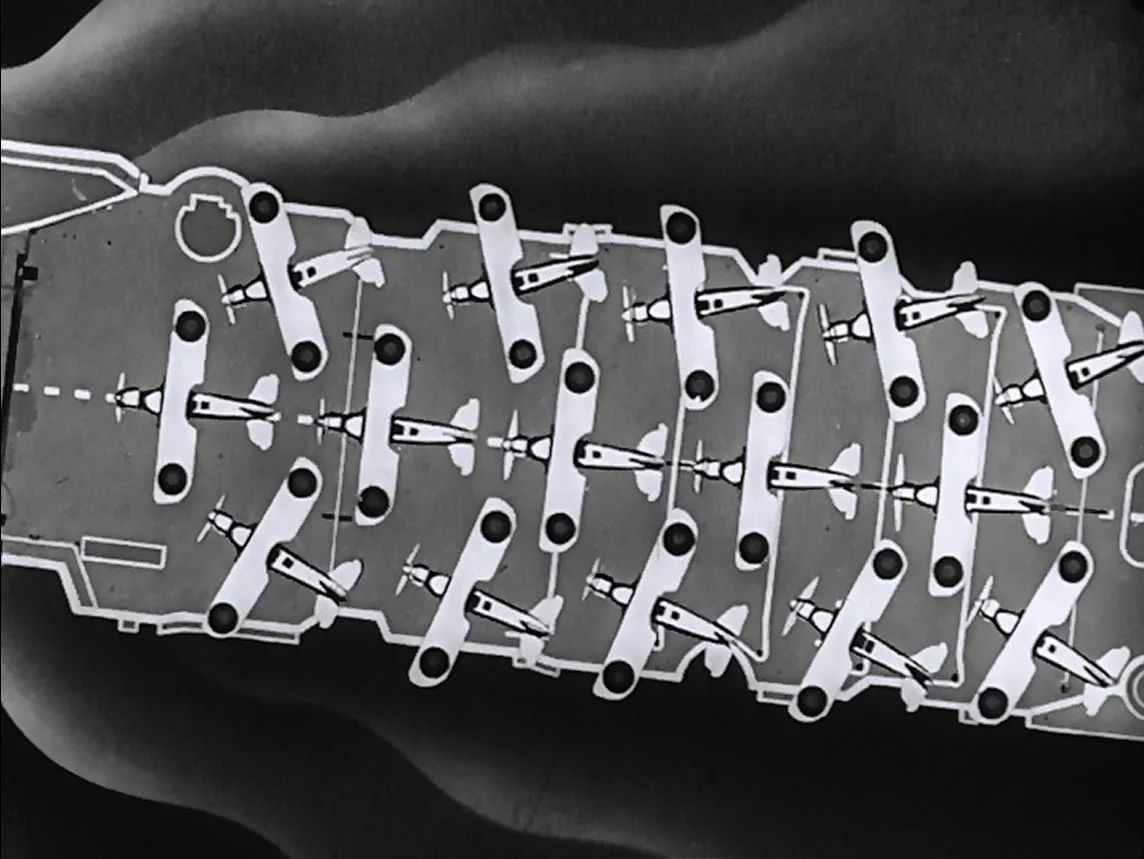

HMS ILLUSTRIOUS, 1940, top profile.

Source: British Aircraft Carriers 1939 - 1945 (New Vanguard). Click on the image for an enlarged view. Illustrious is shown here in her January 1941 camouflage scheme.

Flight Deck

That the Illustrious Class had an “armoured flight-deck” is something of a misstatement.

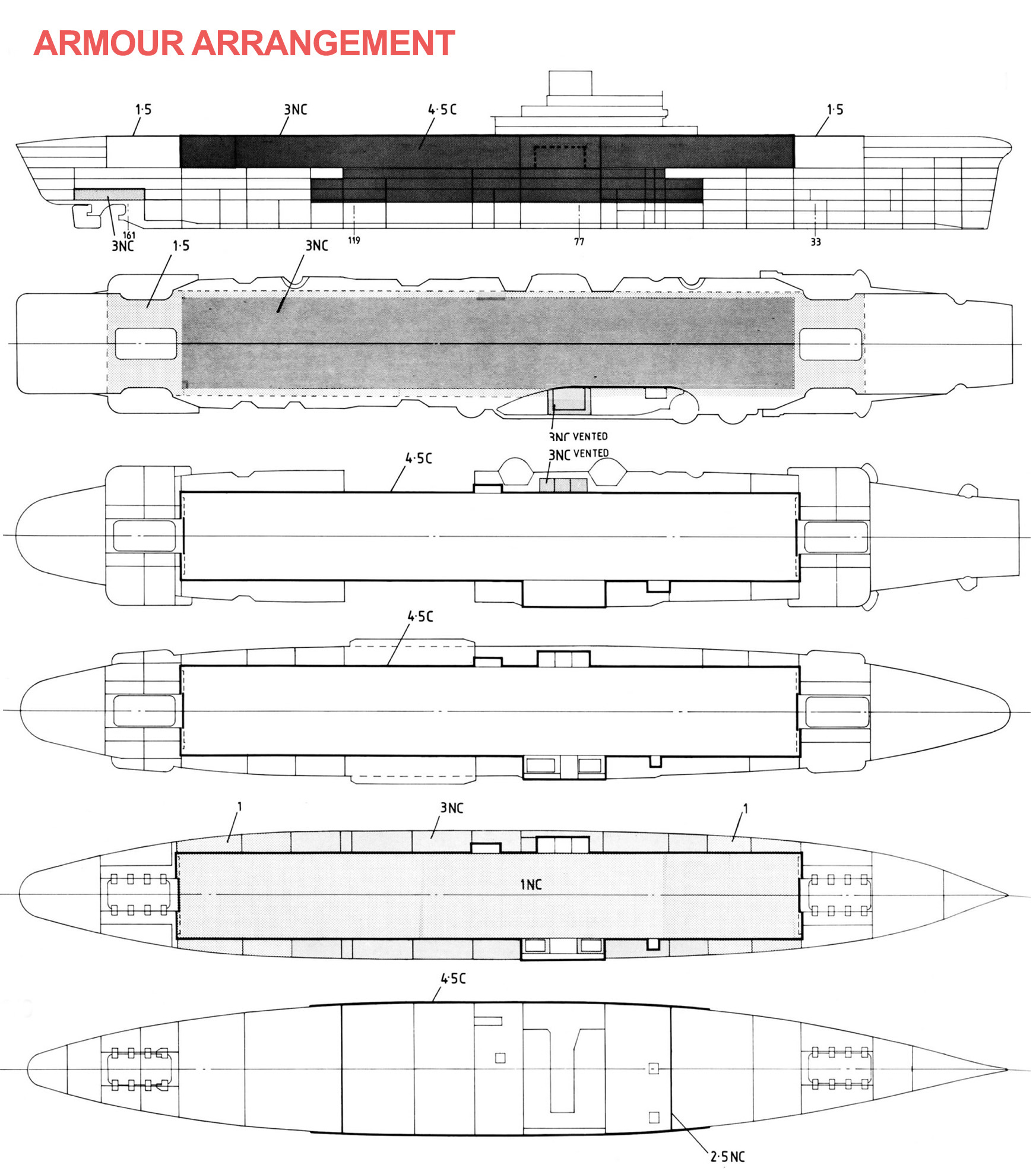

What made the class so unique was an armoured box incorporating the centre of the flight deck between the lifts which enclosed the aircraft and machinery spaces within a protective “cocoon”. The lifts themselves were not armoured and nor was the flight deck fore and aft.

In effect, the 3in armour covered 62 per cent of the flight deck and weighed 1500 tons. Much of the remainder was toughened structural steel.

The United States Navy built its flight decks as though they were part of the vessels superstructure. British carriers, including Ark Royal, incorporated them as their primary strength deck. As a result the flight decks were an integral part of the ship’s hull. This is why the flight deck around the fore and aft lifts was rated as 1.5in armour – for strength reasons, not as protection.

While of roughly similar weight to their United States treaty-constrained contemporaries (the USS Yorktown Class) and HMS Ark Royal, the Illustrious Class necessarily came out as smaller ships.

This was compounded during the early war years by the provision of extensive “round downs” on the bow and stern to improve air flow over the deck.

All three of the Illustrious class carriers underwent flight deck rebuilds to improve operational flight deck space during the war years. Eventually, the usable length of HMS Illustrious herself was boosted to 740ft. Initially, only 620ft had been available.

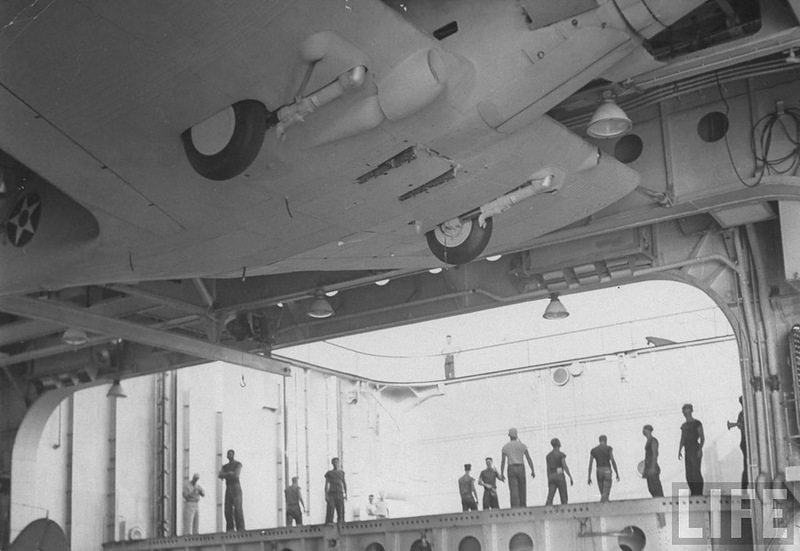

Where Ark Royal had a freeboard to the flight deck of some 60ft, the deletion of the second hangar deck from the Illustrious class in order to preserve stabilitiy reduced this height above the water to 38ft.

The flight deck and aircraft facilities of the class were initially designed to operate 11,000lbs aircraft with an maximum take-off weight of 14,000lbs. This was steadily upgraded throughout the war.

“It is probable that the closed hangar was best suited to an operational concept of small strikes; the open hangar to big strikes. The British desire to protect aircraft from weather as well as enemy attack led both to the closed hangar and, later, to the armoured hangar”

Hangar

The Royal Navy regarded the hangar as a place of refuge for aircraft, not just as a place for maintenance, rearming and repair.

But it was even more than this.

Instead of a simple garage, the Royal Navy was extremely aware the hangar held large amounts of flammable and explosive fuels, oils and ordinance. As such it regarded the vast 458ft x 62ft vault to be in the same category as an ammunition magazine: A space to be well protected and contained.

Then there was the weather. The warm water of the Atlantic Conveyor current mixing with cold Arctic waters can result in especially rough North Atlantic weather conditions. And while RN carriers would be called upon to operate anywhere in the world, Britain naturally expected them to serve mostly close to home. So protecting aircraft, equipment and crew from the elements was a necessity.

Combined, these considerations culminated in the “closed box” an armoured hangar.

Sir Denis Boyd, first captain of HMS Illustrious

But then we came up against a snag. Who suggested an armoured carrier I cannot remember, what I am certain is that we took advice on the menace against which the carrier had to be protected. The RAF assured us that a 500 pound bomb was the largest we would be liable to meet in the next ten years. This was in 1935.

So a carrier was designed to keep out a 500 pound bomb... we were well off the mark. All the rest is wisdom after the event.

Charles Lamb recalled his first impressions of Illustrious' hangar when he went aboard early in 1941:

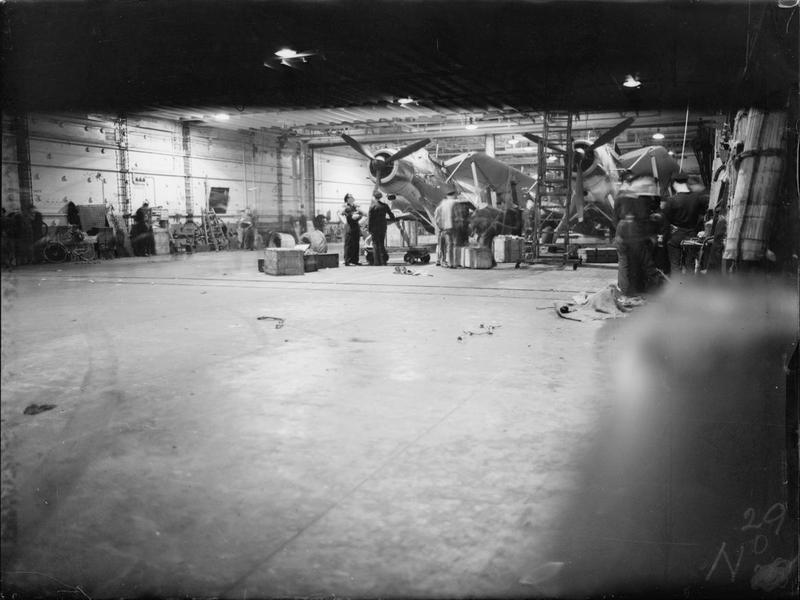

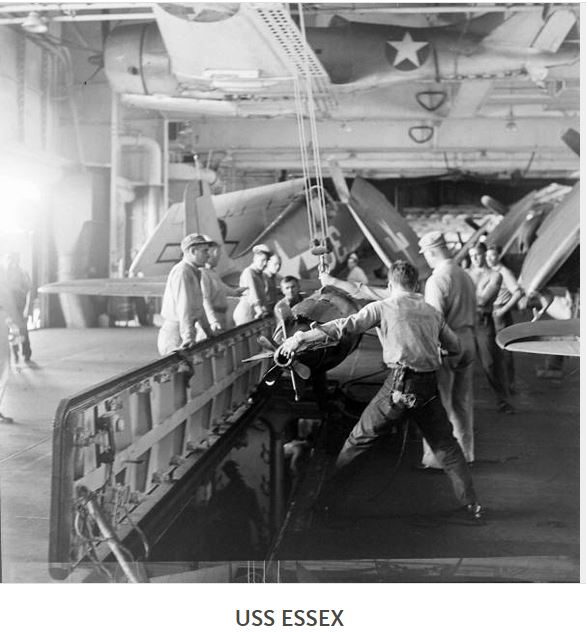

I was looking through the folded wings of almost forty aircraft, all stacked together very tightly, according to some preconceived plans, so that they could all be stowed down below. The wings were almost touching. On the bulkheads, brightly coloured markings indicated fuel points, or connections for high pressure air, oil, water, electric power - all vividly painted in clearly defined colours so that there could be no mistake. Overhead, metal firescreen curtains were rolled and stowed, ready to be dropped in an emergency dividing the hangar into three separate comparments. The whole deck-head was a series of overhead stowages, containing spare aircraft engines, airscrews, long-range tanks, and all manner of objects: but the whole of the hangar deckhead was bristling with little sprinklers a few inches apart, so that in the event of fire at the turn of a switch the curtains would fall and the entire hangar would be sprayed with jets of salt water.

The armoured hangar was intended from the outset to contain the blast of any bomb or shell that penetrated to prevent further damage to the vital machinery and magazines beneath. It was for this reason access was only through double-blast-door lobbies. Workshops were accessible only via the hangar, and nowhere was the hangar wall the side of the ship.

For details of the deck and hangar armour arrangement, see the "Protection" section below.

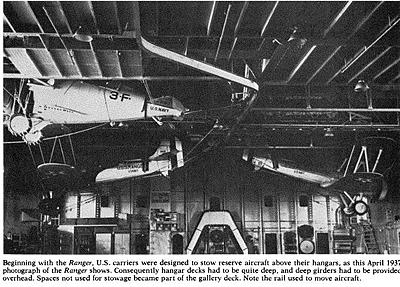

The height of the hangar was maintained at the then British standard 16ft. But, as space was at a premium aboard these particularly cramped ships, this was reduced a little by the need to stow spare aircraft components overhead.

The design office knew – as demonstrated from its notes – that it was vital to provide the largest possible hangar space. The ships were expected to remain in service for 20 years, and the pace of aircraft development was remarkable.

But the width of the hangar was constrained by the need for the structure surrounding the armoured box hangar to support the heavy armour on the flight deck.

Finally, the closed armoured hangar - as with Ark Royal's unarmoured hangar - was intended as a refuge for aircraft from the North Atlantic. Strong winds, heavy waves - not to mention ice and snow - were regular challenges for the likes of HMS Victorious when stationed at Scapa Flow or Iceland.

And that’s before hurricanes are taken into account.

And while the RN adopted deck parks in the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean and Pacific, the logic behind this thinking was demonstrated in December 1944.

Typhoon 'Cobra' sank three US destroyers and damaged nine other ships - including fleet carriers. Also destroyed were 146 US aircraft on the deck parks and in the open hangars (some had caused fires when their fuel-tanks split). All had to be replaced.

A repeat event happened off Okinawa in June 1945 during Typhoon Connie/Viper: This time 76 US aircraft broke loose and were destroyed.

FAA pilot Norman Hanson, Carrier Pilot

As far as aircraft maintenance was concerned, it was naturally the hangar where there was most activity. In temperate latitudes this armour-plated box, capable of holding 30-odd aircraft, was a pleasant enough workshop for the boys. In the tropics it was hell upon earth. In a daytime temperature of anything up to 120-130 degrees Fahrenheit, the slightest movement produced a stream of perspiration. When an aircraft was flown regularly without mishap, its servicing was a straightforward, uncomplicated procedure. Every 30 hours it underwent an ever-increasingly rigorous overhaul culminating— if it lasted long enough!— in a truly major one which was tantamount to taking the whole thing apart and re-building it. It was also subjected to a daily check— tyre pressures, oil, hydraulic and air pressures, the correct functioning of ignition, instruments, radio and guns. If an aircrew was fortunate and their aircraft was in the right place at the right time, this daily check could conveniently be carried out on the flight-deck.

If they were not so lucky, however, the daily check had to be done in the hangar, that ill-lit, unbelievably noisy, unbearably hot dungeon where aircraft were lashed down cheek by jowl, surrounded by straining, swearing mechanics clad only in a pair of shorts— wringing wet from perspiration— and gym-shoes. Here they toiled, fuming at obstinate nuts, red-hot pipes and sparking plugs; and with the roll or pitch of the vessel calling constantly for a change of balance. Their hands never ceased to clear sweat from their eyes and within ten minutes their faces were covered in greasy filth and grime, rendering them almost unrecognisable.

They were great chaps. One of a sailor’s God-given rights is that which moves him to moan like the clappers at anybody or anything at any given moment; and these lads were no exception. But when called upon to pull out all the stops they never failed us.

“Open Hangar. Good ventilation, easy to warm up planes, mount large strike, side lifts, more planes. Closed Hangar. Stronger, lighter hull. Much safer against fire, easy to armour, planes protected from weather and some enemy action.”

“In particular, the lift wells were the Achilles heel of the armoured deck. (But) The open sides of the open hangar were vulnerable to the most trivial attack – machine guns, splinters as well as light bombs.”

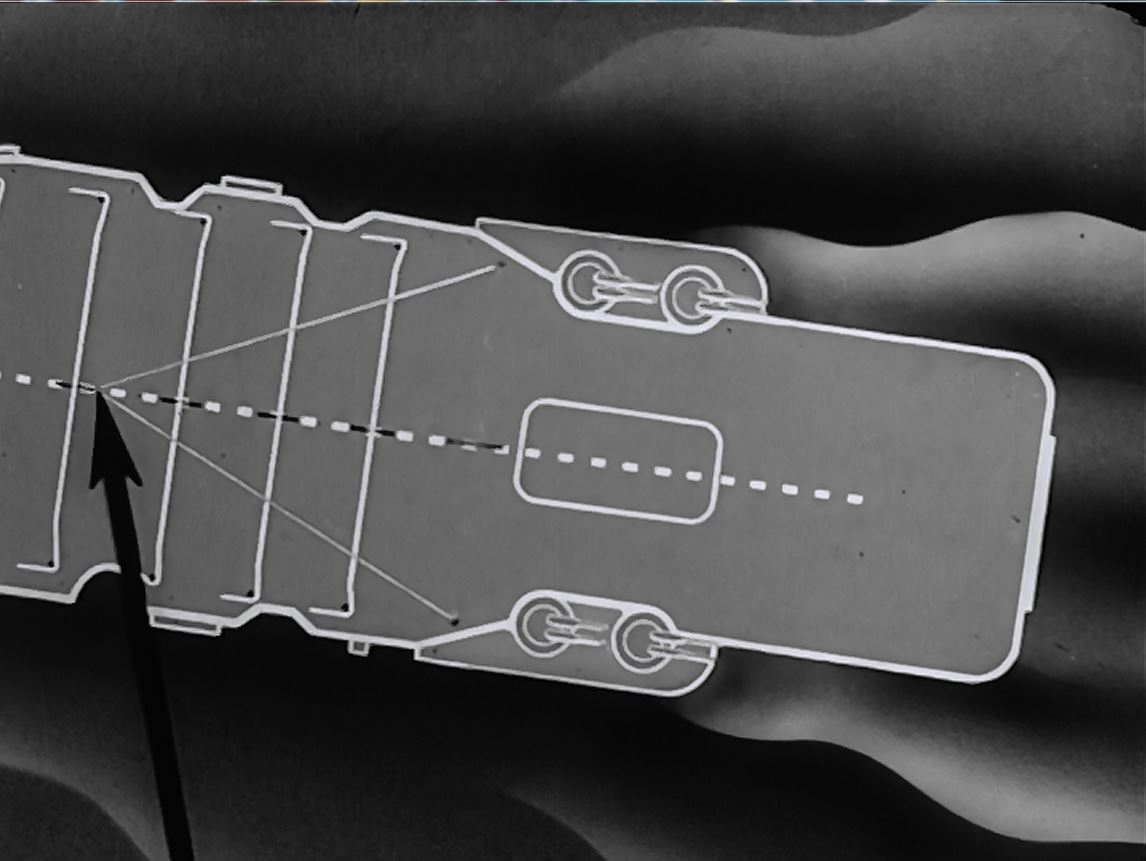

Lifts

In British carriers the placement of the aircraft lifts was of particular importance. Piercing the armoured box around the hangar would have structural implications for the entire ship.

Fortunately, placing the lifts at the front and rear of the hangar space was both convenient and desirable for hangar operations.

Aircraft that had landed on could be struck below via the front lift. During take-off operations aircraft could be moved via the rear lift well.

The lifts themselves were as small as practicality could allow. As built, Illustrious’ lifts were 45ft by 22ft. This was a deliberate decision. The smaller lifts offered reduced structural weakness and limited the “Achillies heel” effect of the unarmoured space.

The lifts were considerably stronger than those used in previous ships. They could carry 13,440lb in a 30-second cycle (one way loaded, opposite way unloaded), but were upgraded during the war to carry 15,000lb. This compared favorably to the 45 second cycle times of the contemporary USS Yorktown. However, the Yorktowns had three lifts.

The lifts of the Illustrious Class were also designed to continue operations despite a degree of distortion. While this added considerably to their expense, it was considered necessary to maintain the fighting efficiency of the ship after moderate damage had been sustained.

Nevertheless the rapid growth in size and weight of aircraft during the 1940s was not fully anticipated. This was to have severe implications for available aircraft types all through the war.

“The difficulties in the design of such a device are not often realised. First there is the impact as the hook engages the wire and has to start it moving from rest. As the wire begins to pull out a mass of pulleys and tackles have to be set in motion – fast – and only then does the hydraulic ram begin to function.”

Arrester Gear

1930s British carrier doctrine was similar to that of RAF airfields: landed aircraft had to be removed from the “runway” as quickly as possible. On board a carrier, this involved striking the craft below via lift immediately after landing and before the next aircraft made its approach.

While this was a “safety first” principle, it was abandoned even before the outset of World War II as it slowed landing operations considerably. Aircraft would be parked on the bows behind the protection of a crash barrier within a minute of landing as the next aircraft came in.

Such a deck park landing system shortened the time the carrier needed to steam into the wind. This, in turn, improved the fleet’s general rate of advancement along its desired course. Regular diversions to land and launch aircraft could slow a battle group’s progress considerably.

Notably, Captain Boyd of HMS Illustrious was the first RN carrier commander to insist upon the use of this method once he took the helm in 1939. Previous captains had been dubious as to the value of the crash-barrier system - but they had been operating biplanes with very low landing speeds. Captain Boyd was among the first to operate the Fulmar.

In 1945, HMS Implacable brought down 18 aircraft with an average 32 second separation.

As high-speed aircraft became more necessary, so did the requirement for high-speed landings. Such aircraft could already be launched with the assistance of a catapult. But landing was another matter.

Stronger arrester systems needed to absorb greater shock and restrain greater weight. And when the arresters failed – or were missed – there needed to be a method of last resort to prevent the careening aircraft from slamming into the forward deck park or dropping through the elevator.

The MkIII arrester set was installed in all wartime carriers after being trialled in Courageous in 1931. The unit fitted to Ark Royal was able to arrest 8000lbs at 60kts. Later modifications, as fitted to Indomitable, could snare 11,000lbs at 60kts.

The Illustrious Class had six wires fitted aft and amidships. These were positioned much further forward than in US ships, though wartime refits soon saw an additional two arrester wires strung behind the aft lift once the large round-downs were flattened to allow more effective deck area.

Illustrious was the only ship of the class not to have a two arrester wires positioned forward of the island, intended to accommodate emergency deck landings from over the bow.

“I had been shot off once or twice before from British catapults, but there was a difference between the two. The British method involved hoisting the machine up on to a trolley where four claws connected up with four spools on the belly of the plane. When the trigger was pulled trolley and aircraft shot down the deck, the trolley fetched up against a stop near the bows, its front legs collapsed forwards, and the machine was airborne.”

Accelerator

The Royal Navy used a central brace system for its accelerated launch system, chosen for its ability to trolley-launch seaplanes as well as the way in which it distributed the forces of launch more evenly through an airframe.

This trolley system had four collapsible gripping arms which could be quickly stowed away from the deck, but it took time to adjust the length of these arms to suit different aircraft types. Aircraft also had to have four attachment points incorporated into their structure.

The US system simply required a wire strop looped from a rolling shuttle to be connected to two attachment hooks, usually in the aircraft landing gear, and appropriate launch forces selected.

As a result, the trolley was a slower system than the US Navy’s tail-hook catapult. While the US system placed greater strain on aircraft, it was more suited to the demands of high-intensity operations.

The British accelerator was designed to launch 11,000lbs at 66 knots. With some modification it proved capable of launching 14,500lb at the same 66 knots using the American-style tail-down method.

During the war all three of the Illustrious Class had their accelerators modified to accommodate the US method in order to operate US-supplied lend-lease aircraft.

Regardless of the catapult style, unassisted take-off was still much faster. A practiced air and deck crew could fly off one aircraft every 10 seconds.

The advantage of an accelerator was that it allowed more aircraft to be ranged on deck than would accommodate safe unassisted take-off distances. This meant larger strike groups.

While the BIII accelerator was rated with a 40 second average launch interval, times would vary according to deck crew experience and aircraft types. Cycles would range from up to a minute per launch, to once every 20 seconds..

Early designs had two such catapults on the Illustrious Class, but it was observed that they were too close together for concurrent operation so only one was fitted.

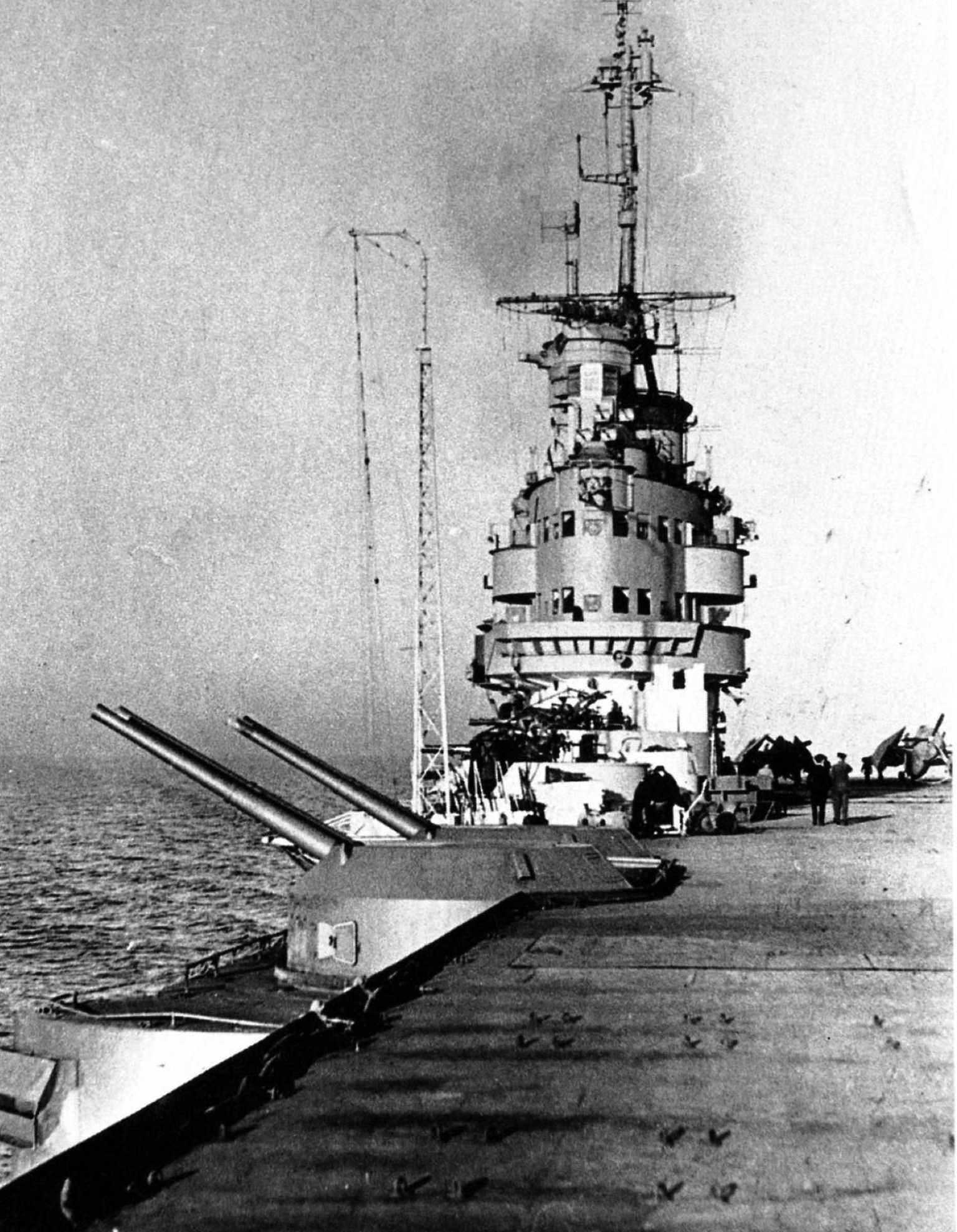

The bridge of HMS FORMIDABLE in 1941 while undergoing repairs in the Norfolk navy yards.

“Because of the fire on HMS Ben-my-Chree when she was sunk, the RN was always very conscious of the fire hazard in the hangar. The closed hangar was separated from the rest of the ship by air locks and with the lifts up was reasonably airtight so there was insufficient oxygen to support a major fire.”

Fire Suppression

Fire was the main enemy of every aircraft carrier. The amount of flammable materials in a hangar – not least aviation fuel – was considerable.

The first objective was to stop any fire from spreading. All major navies adopted the use of roller-blind style shutters to divide hangars and cut-off air to the affected area. In the case of the Illustrious Class, these consisted of four steel fire curtains which could divide the hangar into thirds.

While such curtains would prove of little effect in the face of damage caused by the penetration of enemy bombs, the closed hangar itself would dramatically reduce the chances of the fire from spreading to the rest of the ship.

Britain’s fire dousing system was regarded as the most effective of the time. The sealed hangar and a high-pressure sea water spray system proved capable of containing hangar fires within minutes. But the effectiveness came at a cost –aircraft and equipment would be drenched in salty sea water, often producing write-off levels of damage to corrosion-prone alloy components and wiring.

HMS Illustrious – despite being hit by eight bombs ranging between 2200lb to 550lb – never faced an uncontrollable fire. This was the ultimate vindication of her design and fire-fighting equipment. The sealed hangar isolated the machinery spaces from the bomb blast and spread of its fires. Those fires which had started in the wardroom flat and bow machinery spaces were contained by damage control until Malta dockyard was able to assist in extinguishing them.

It was a similar story for HMS Formidable: The fires in her bow after a 2200lb bomb blast in 1941 were restricted to the forward spaces. In 1945, fire from burning fuel and aircraft mostly spilled harmlessly over the side of the deck and only small quantities seeped into hangar spaces.

One of the RN armoured carriers' most controversial features was its aviation fuel storage system.

Large coffer dams were suspended below the waterline in seawater-filled chambers under armour. This dramatically reduced the amount of fuel carried for the amount of space dedicated to the fuel systems (Victorious only carried 40,500 gallons).

But it brought advantages.

The water pressure helped force the fuel into the distribution pipes. But it also prevented explosive vapor-filled voids from forming as the aviation fuel was used up.

The passive defence features of this system also protected the fuel containers from rupturing through shock and whiplash. And if one did, it would spill its fuel into an environment already filled with liquid - significantly reducing the chance of dangerous vapor-air buildups.

While costly in terms of reducing the given amount of avgas stored in a set amount of space, no British carrier completed with such a system ever suffered a serious bulk fuel fire or explosion - despite suffering heavy and extensive damage.

It was the lack of such passive defence systems that doomed the Japanese navy's armoured carrier Taiho.

Protection

Standard naval doctrine of the pre-war years was for a ship to be armoured against the equivalent of its own offensive capability.

In the case of an aircraft carrier, this was regarded to be the 250kg (550lb) bombs its dive bombers could deliver.

This was Britain's answer to the problem presented by 1930s wargaming: The first air group to make contact with the enemy invariably won. Naval doctrine was presented with two options: Build more (smaller) carriers, or build carriers better able to survive air attack.

Wargaming had also exposed another weakness of the carrier: Its constant need to move out of the protective screen of the battle fleet to deploy and recover its fighters meant it could become exposed to enemy cruisers and destroyers.

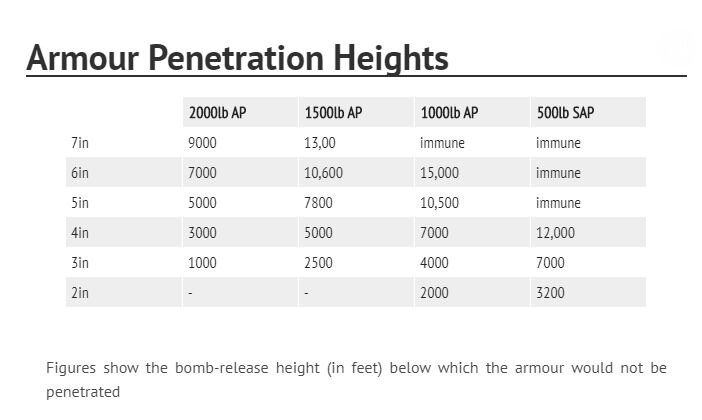

The result was a requirement to protect carriers against 6in shellfire and 500lb plunging bombs.

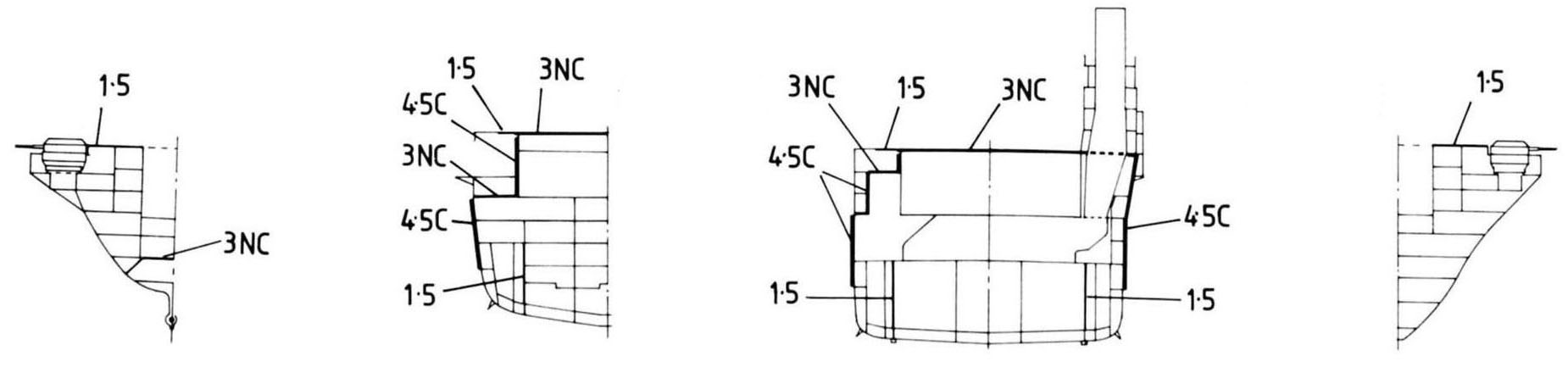

To achieve this, the “armoured box” walls were given 4.5in C grade (face hardened) armour plate and the hangar deck was 3in NC grade plate.

The deck was expected to resist a 550lb (250kg) semi-armour piercing bomb dropped from below 7000ft and 250lb (110kg) SAP bombs from below 11,500ft. It was calculated the deck could resist a 1100lb (500kg) armour-piercing bomb only if it was dropped beneath 4500ft.

Against 6in shells, the hangar walls would resist fire from over 7000 yards and stop 4.7in shellfire from all ranges. The 3in deck became vulnerable to plunging 6in shells beyond 23,000 yards.

The ends of the hangar were likewise protected with 4.5in C (face hardened) armoured bulkheads. The vulnerable space between the unarmoured lifts and the hangar could be closed off by 4.5in C (face hardened) armoured doors when in action.

- Sir Denis Boyd, first captain of HMS Illustrious

The only bomb that hit the armour went right through it and exploded on the floor of the hangar. Now had there been no armour that bomb would probably have exploded in the engine room and this could well have been disastrous. All the other bombs struck outside the area which had been armoured.

As usual there is no easy answer to your question. The design of the Illustrious shook the world as the words ‘an armoured carrier’ had a magic of their own, but as you see it was not quite true. When she was in the design stage I asked if I could be considered for commanding her. That I did is my lasting pride.

The hangar itself could be divided into thirds (one squadron each section) by two heavy steel fire shutters inside the hangar itself, and another shutter at the entrance to each of the lift wells.

The “armoured box” containing the hangar space did not extend the full length or width of the flight deck. As a result, the armoured hangar floor transitioned to 3in plate where it extended outside the hangar and above the 4.5in main waterline belt. This was to provide a standard degree of protection to the magazine and machinery spaces below.

Other vital spaces were also armoured. The steering compartment was protected by 2.5in armoured bulkheads and a 3in armour hood. This extended along the line of the central shaft to the hangar deck.

Of the 23,000 tons the Illustrious Class displaced, 5000 tons was armour. 1500 tons of this was on a 458ft stretch of the flight deck.

The height of this weight forced the ships to be given a lower profile to maintain stability. This, again, imposed limits upon the hangar space achievable within treaty limitations.

The Illustrious Class had underwater torpedo protection rated against a 750lb warhead. It was provided by empty compartments intended to dissipate the blast of an explosion, along with wing tanks for the fuel oil.

Rear-Admiral Vian, who commanded Britain's last and largest carrier operation of World War II, felt the heavy armour protection of his ships had been vindicated off Sakishima Gunto during Operation ICEBERG

The armoured flight deck, which was a feature of British fleet carriers, paid a dividend on this occasion. In spite of the direct hit, Indefatigable was able to operate aircraft again within a few hours. American carriers similarly struck were invariably forced to return to a fully-equipped Navy Yard for repairs. This led to discussions as to the relative virtues of British and American design. The British carriers, with their armoured decks, higher safety precautions, and closed hangars, could stow many fewer aircraft than their American counterparts. On the other hand events were to show that had our carriers not had armoured decks, Task Force 57 would have been reduced to negligible proportions during the Okinawa operation. The Americans, with their greater number of carriers, could quickly replace those put out of action. Apart from this salient feature of design, the American carriers had many advantages over the British, including greater speed and endurance, and a more effective anti-aircraft armament.

Armament

Britain’s carriers had a particularly heavy gun armament for their time. This was the outcome of tests during the 1930s which saw ships pitted against simulated air raids by new radio-controlled Queen Bee target drones. The exercises had appeared to prove two things:

Fleet anti-aircraft guns could deal effectively with attackers. But some would almost always break through.

That fast attacking aircraft would breach the fleet’s screen before ready response aircraft could be launched and obtain intercept positions.

The distinctive “four quarters” defensive arrangement of countersunk “pill-box” 4.5in BD Mk II Dual Purpose gun mountings is a defining feature of the armoured carriers.

These twin gun mounts, positioned in pairs, were countersunk into sponsons projecting from the flight deck to reduce their impact on flying operations. While they had a low profile, these 4.5in mounts were intended to be able to fire over a “clean” flight deck.

Three Mk IV fire-control directors were similarly conformal, mounted around the flight deck on hydraulic hoists and only raised to control fire when the carrier was under direct attack. A fourth fire-control director on top of the island to control the two mounts on the starboard-forward quarter for independent operations.

Each director was paired with a set of 4.5in mounts, though each could control a full broadside. The bridge mounted director was capable of directing all eight mounts in barrage fire.

Six eight-barrelled “Pom-Pom” Hk VIA mounts were dispersed around the flight-deck edge and on the island. The large circular screens around S(starboard)1 and S2 mounts were mainly for flight deck aerodynamic reasons but also offered a degree of protection from blast damage.

The Illustrious Class carried 400 rounds of ammunition per barrel for its 4.5in HA mounts. Some 1800rpb were carried for the 2pdr pom-poms.

The exact number, style and arrangement of Pom-Pom, 40mm Bofors, 20mm Oerlikon varied between each ship as the war progressed.

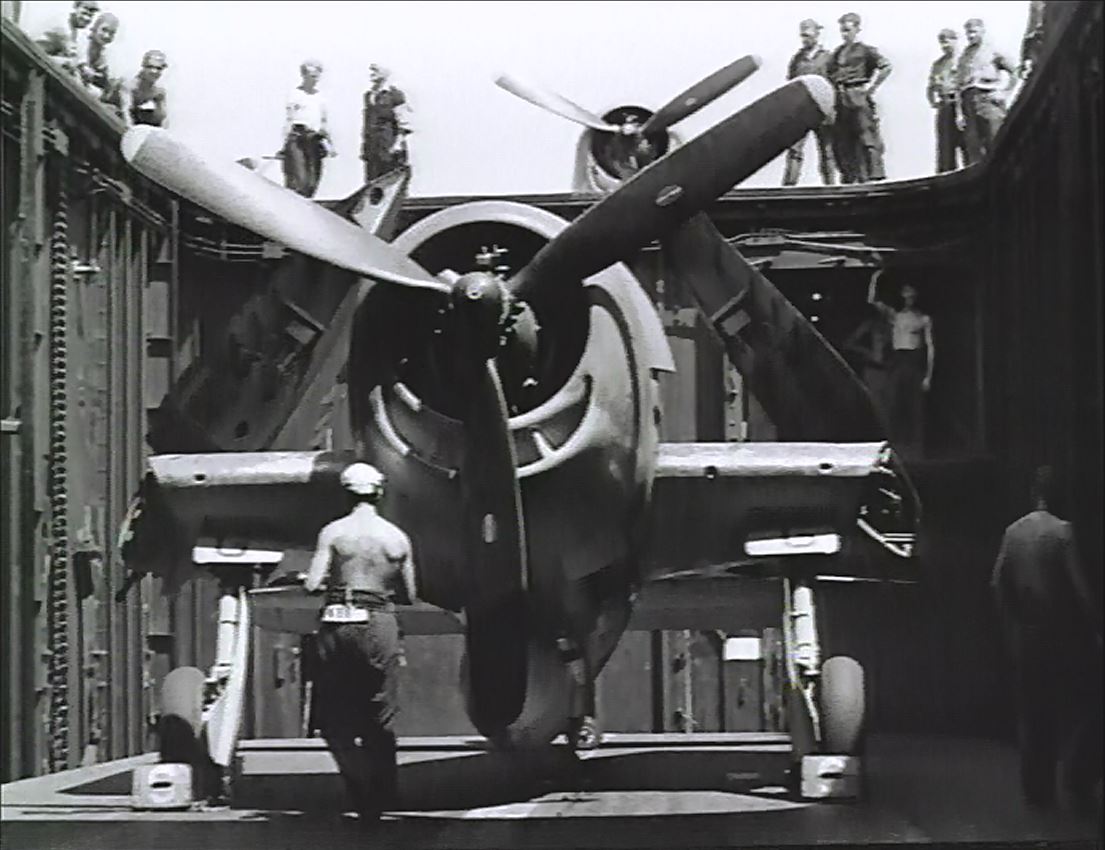

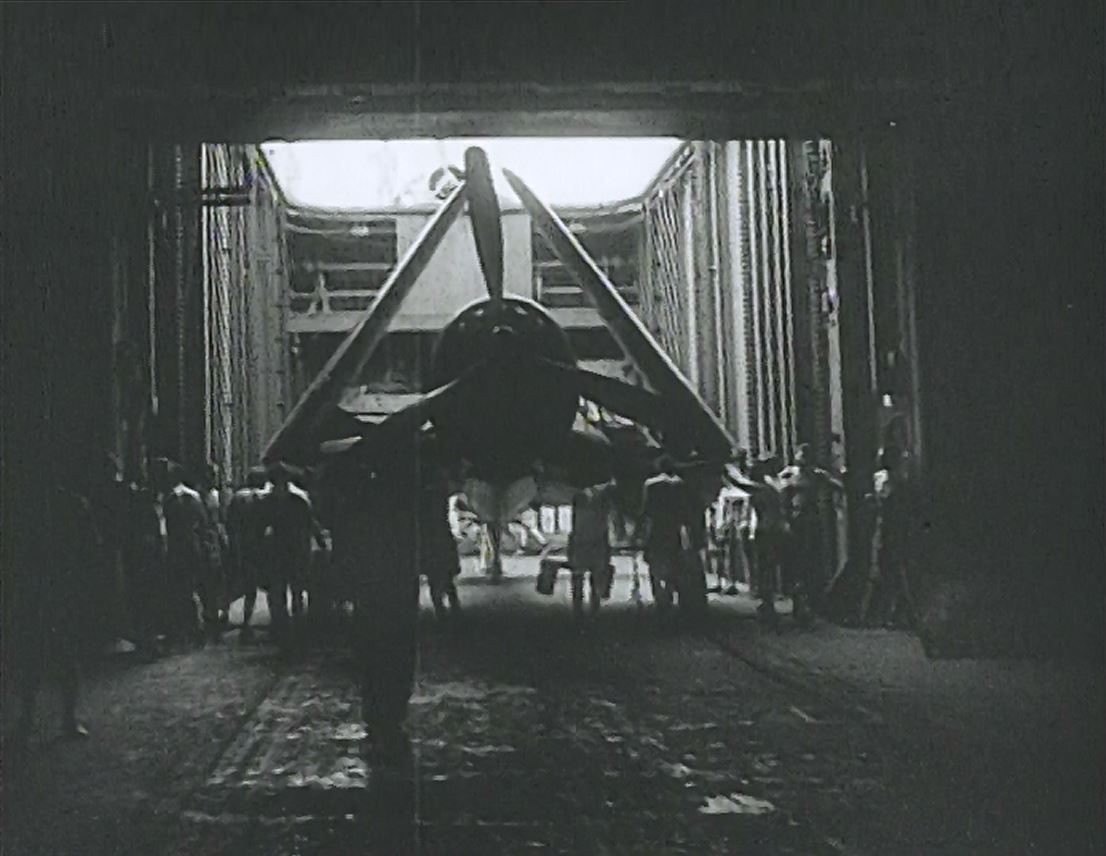

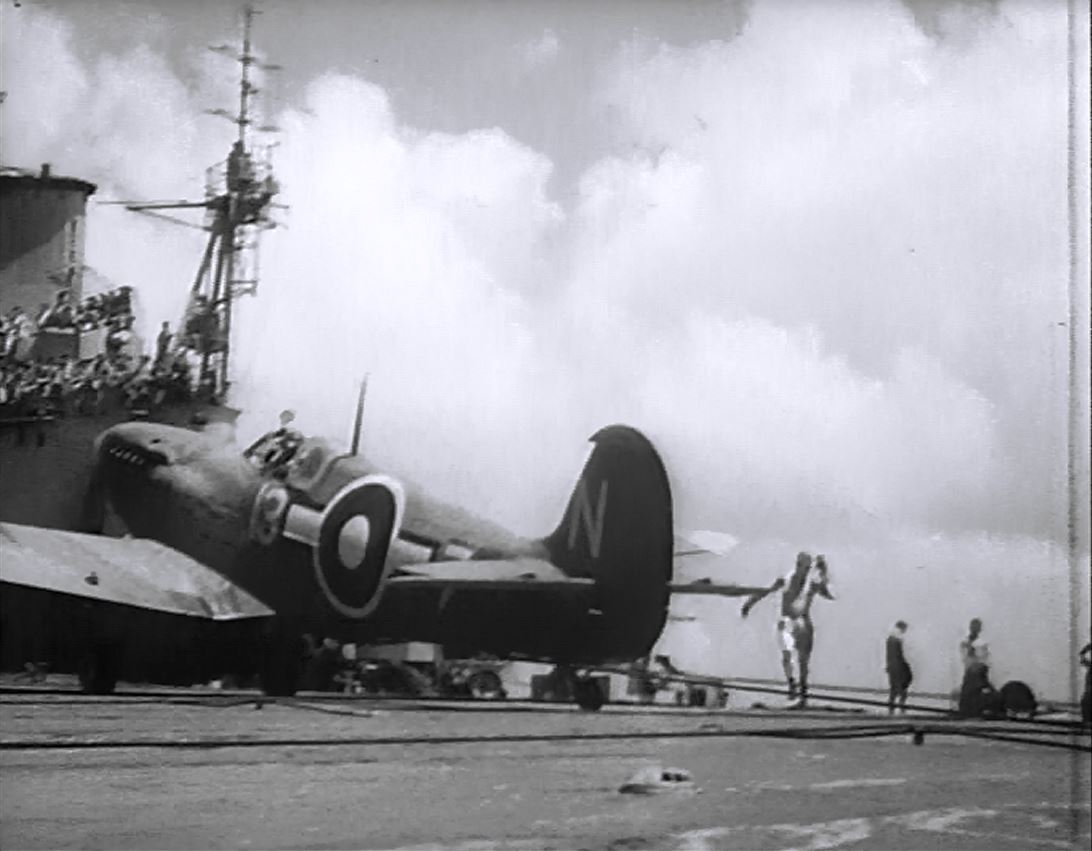

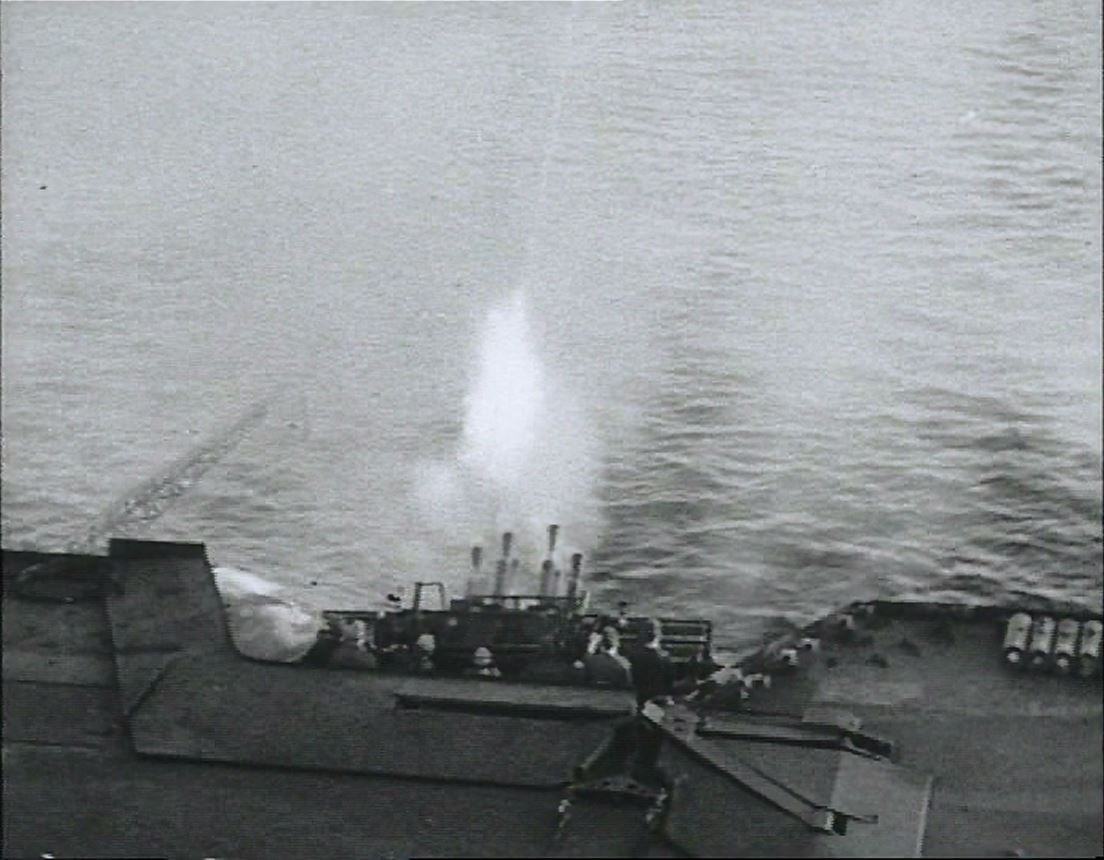

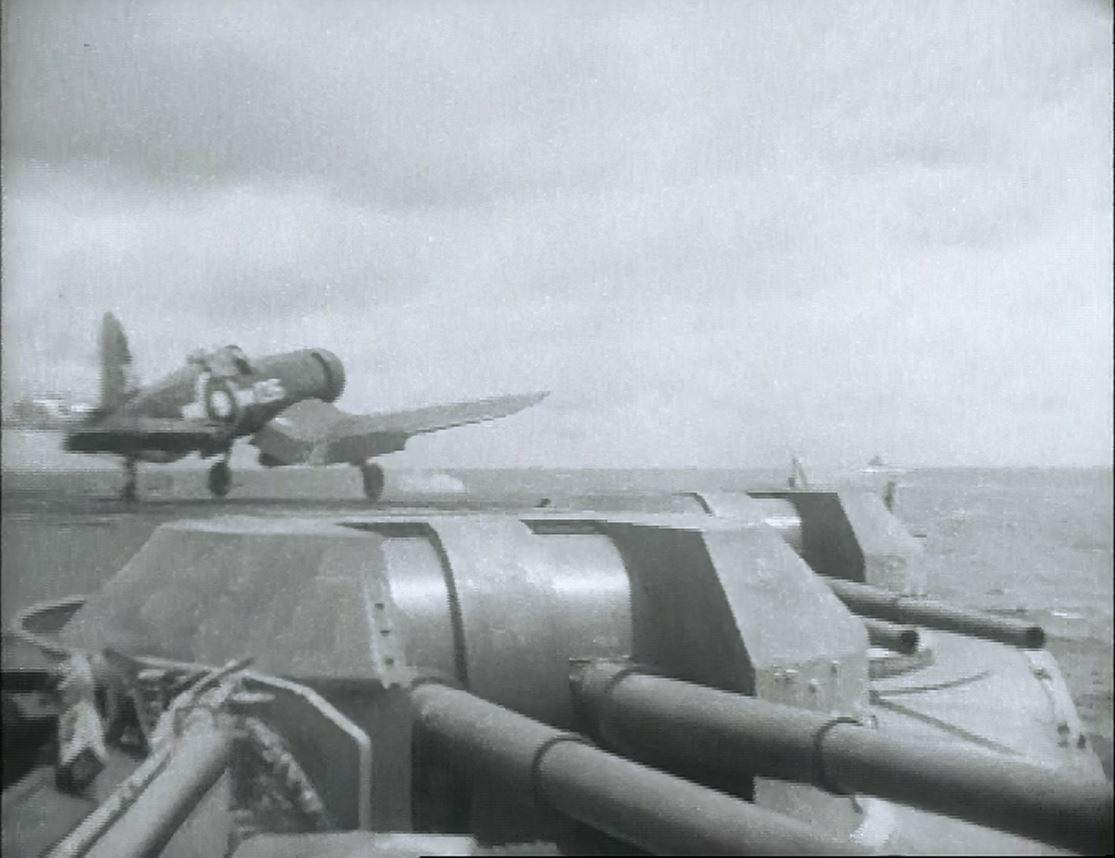

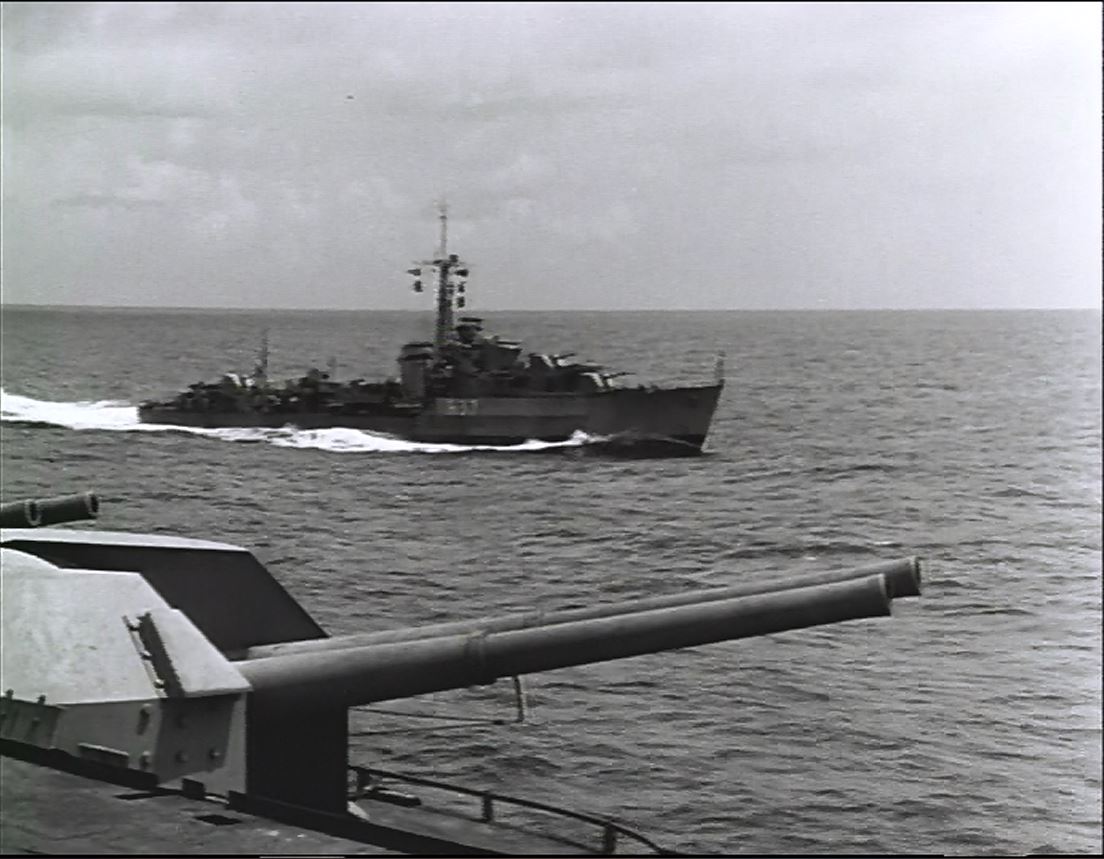

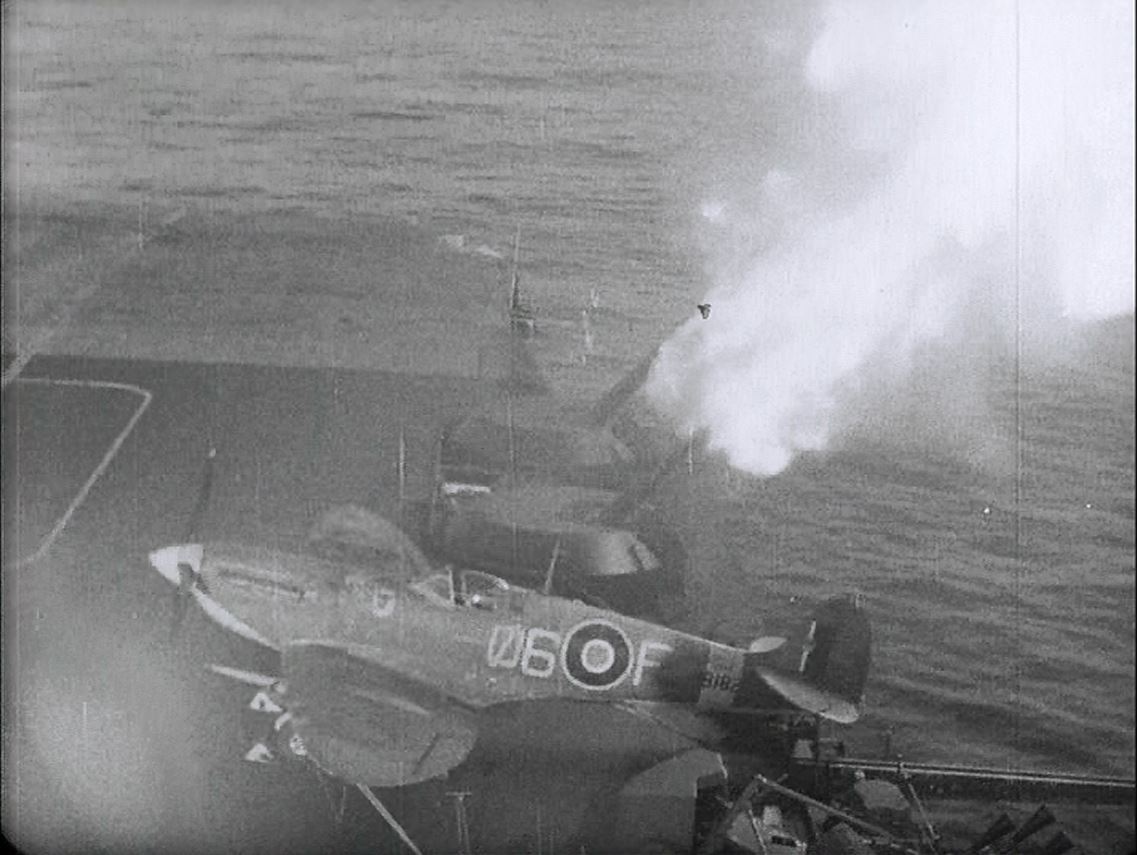

A flight deck scene made up of a series of screen captures from a 1940s newsreel film aboard one of the armoured carriers.

AMMUNITION & BOMBS

The total capacity for the Illustrious class air group’s ammunition was 180 tons, with bomb weights varying from 500lb to 20lb. Torpedo capacity was 45 18in propulsion bodies, with the warheads being stored separately under armoured mantlets. The idea was to give every aircraft in a torpedo-bomber only air group a weapon to carry. In a mixed air group, the extra capacity was to serve as spares.

As completed, the bomb capacity was:

- 45x torpedo

- 250x 500lb SAP bombs

- 400 250lb SAP bombs

- 250 250lb “B” bombs

- 100x 100lb AS charge

- 600x 20lb

A) 40mm PomPom magazine. B) Bomb & firework rooms, 4.5in magazine. C) Bomb and warhead rooms. D) 4.5in and firework magazine.

The bomb and magazine rooms were buried deep within the hull, at the very heart of the ship. Most were encased by the 120 and 100lb NC armour of the hangar deck, and the 180lb C plating on the ship’s sides. Protection for the bomb and torpedo magazines themselves was 3in cap protection where the magazine was not beneath the armoured flight deck, 2in if it was. The spaces also had 2in and 1.5in NC bulkheads.

The bomb rooms were serviced by lifts which had access to the ship's deck, one of which opened from the island.

The 4.5in gun magazines were similarly buried in the heart of the ship. The rounds and their charges were carried to the mounts in the front and rear of the ship by an extensive conveyor belt system running along the ship's centreline before branching to individual mounts.

“Tricky could somehow manage to bring us up-sun and above our practice bogey nearly every time. He made use of a quirk of the type of radar that we had, as it had ‘null’ spots at certain heights and distances. This allowed him to assess the height of any approaching raid without having the more modern height-finding radar in the ship at all. Being a practical scientist he had worked this out for himself.”

Commander R 'Mike' Crosley, DSC RN, "They Gave me a Seafire" :

Lt E. Lewin, DSO, DSC, RN, a fighter pilot from Ark Royal, had come to Yeovilton to get ADR operators trained for interception duties in carriers and in ‘air defence ’ cruisers. A ‘Schooly’, Lt/ Cdr Coke, RN, who organised the daily work of the school itself, managed to do this on ‘a shoestring’ and without fuss. The Wall’s ice cream tricycles were the ‘aircraft’. The ‘pilots’ pedalled them under radio directions from a small transmitter in the Control Tower, which was the ‘aircraft-carrier’. Some tricycles were enemy ‘bombers’. They pedalled slowly. Others were ‘fighters’. They pedalled faster — but only a little faster, we noticed. The pilots of the bombers and fighters carried their wireless sets where ice cream should have been. The bombers steered a course for the carrier, and the fighters were sent to intercept them. They steered whatever course and speed that Lt/ Cdr Coke ordained, using a compass below the handlebars to give them the required direction and a metronome on top of the ice cream compartment to give them their pedalling airspeed. Neither bomber nor fighter could see where they were going, so we watched each collision as it occurred. We would then listen to the polite comments of the fighter pilot towards the bomber as they unseated each other in mock combat . Sometimes there were r/ t failures. The Tower then lost contact, and aircraft would get lost on the airfield and sometimes be seen pedalling slowly down the roads between the hangars or by the Captain’s office. We suspected that they had purposely switched off and were making a beeline for the wardroom bar. There was no let -up, come -rain-come-shine. They even worked during the lunch hour. Some would take sandwiches and beer with them. They kept them in the ice cream compartment, munching them while they pedalled. It was odd to see, at times, a fighter making about 1000 knots equivalent speed. When we asked him why, he said that he had had to ‘land’ to have a ‘strain off and was making up for lost time.

Radar

Work on HMS Illustrious had been proceeding on time. But the late decision to add radar was to delay her completion by three months.

It had become increasingly obvious as the carriers were being built that RDF (radar) was something of a game changer.

The Royal Navy’s fear that there would never be enough early warning to allow interceptors to be effectively launched was beginning to abate. The ability to guide aircraft already in the air was also an exciting proposition.

The Type 79z fitted to Illustrious and her sisters in 1940 was one of the first production air-search radars. It had separate transmission and receiving aerials. For the armoured carriers, the transmitter required the late addition of a new mast. The ad-hoc nature in which these were applied would become a key visual identifier of each ship. On Illustrious it was simply a pole placed alongside the aft portion of the island.

This early radar, one of the first capable of tracking aircraft, was also surprisingly reliable. It had its limitations, however: It had a 70-degree beam width and was not effective at locating low-flying aircraft.

The anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Curlew - active with a Type 79 radar from September 1939 - proved to be the cornerstone of the defence of Scapa Flow and the North Sea in the opening days of the war, effectively directing the ill-suited Skua fighter-bombers to disrupt incoming Ju88 raids.

This direction potential was rapidly proven by HMS Ark Royal's Air Signals Officer, Lieutenant Commander Charles Coke. Of his own initiative, he arranged for HMS Sheffield and HMS Curlew to preserve compulsory "at sea" radio silence by sending him reports by flag and semaphore. HMS Ark Royal did not have radar fitted. Using a portable plotting board, Coke then used these reports to direct Ark Royal's CAP from the wireless office.

It proved an immediate success - even though it could take him up to four minutes to gather the information from Sheffield, manually make a directed intercept plot, and then transmit orders via morse code. It was a skill rapidly adapted and quickly spread among carrier signals officers - though at an unofficial level.

Carriers such as HMS Illustrious, Formidable, Indomitable - and particularly Victorious - embraced the concept as they had air detection radars fitted from completion. They did not, however, initially have dedicated fighter direction plotting rooms.

Interestingly, the chief recruits for this emerging Fighter Direction Officer role tended to be actors who had joined the RNVR. HMS Illustrious, at one time, had up to four famous names using their dulcet tones to calmly and clearly inform fighter pilots of what they were up against.

By May 1941, the somewhat "amateur" role had won enough respect in the Admiralty for Coke to be formally appointed as the director of a new Fighter Direction School at Yeovilton.

Fighter direction facilities initially consisted of no more than a corner of the plotting office, a few voice pipes, a portable R/T set and an adapted portable plotting board. But the importance of the role saw this rapidly expand evolve.

By 1942 the Fighter Direction Office had a Main Air Display Plot (MADP) on which all plots were tracked, and Intercept Plots which calculated the most effective approach vectors for the CAP. Even at this early stage, the FDOs of different ships were linked via portable R/T sets to coordinate their efforts.

While the Air Direction Officer (ADO) had by now been both an unofficial and official feature of fleet operations for some time, the Fighter Direction School soon evolved the multi-layered structure into the Action Information Organisation - (AIO) which was spread across several radar-equipped ships in a heirarchy designed to control the CAP as well as detect and direct countermeasures against incoming raids. In place by 1944, this technique proved of particular value against kamikaze attacks.

The carriers themselves had their radar suite's upgraded through the war. The Type 79 was replaced by the Type 281 (air warning) and 285 (4.5in gunnery) through to the Type 277 (height finder) and 960 (air warning) sets. None would have the US SM-1(CXBL) set fitted as per Indomitable as its 2 ton weight was deemed too great for the ad-hoc mast arrangement aboard the first three ships.

The RN combined radars with different wavelengths to achieve fuller coverage. Here HMS Victorious displays a suite common to RN carriers in 1945: A Type 281B is aft and a Type 279 is at the masthead. The small dipole above the 281 is the Type 243 IFF. On the foremast is the twin-cone Type 252, and the array beneath is the Type 243. A Type 242 IFF can be seen just behind the funnel. On top of the bridge is a Type 277 height-finder. In front of the bridge is Type 282 pom pom control radar.

- Norman Friedman, Naval Radar

Inside the machinery control room of HMS VICTORIOUS, December 1941.

“Experience proved, however, that high speed in a carrier was an essential feature to enable the ship to keep station, operate aircraft (which might necessitate changing course to turn into wind) and to meet other tactical considerations.”

Machinery

The Illustrious Class was a first for British warship construction in that they had a triple-screw arrangement. Six boilers were placed in three groups of three dispersed in different boiler rooms. These provided steam to three sets of turbines.

Sea trials produced a degree of vibration throughout the ship, particularly in the island. But this was felt to be within acceptable levels.

The trials were conducted with parvanes streamed as they were under wartime conditions. Estimates placed her top speed at 31 knots. All three ships achieved maximum speeds under operational conditions of 30.5kts

Average top speeds were in excess of 28knots - much as their American and Japanese counterparts (which rated up to 34knots in trials but not in dirty, operational conditions).

“Most of the big fleet carriers had the big island to starboard on the flight deck. It was a homing beacon, a lighthouse, a promise of security in the treacherous wet expanse of bare, heaving deck and cold grey sea.”

Stability

With HMS Ark Royal as a template, these ships were some 22ft lower due to the omission of the second hangar deck in order to preserve such stability.

Ironically, this lowness of the flight deck to the sea reportedly gave approaching pilots the impression that their decks were bigger than that of the Ark Royal itself.

In reality, however, they were considerably shorter than Ark Royal. This could make pitching in heavy seas a problem for delicate aircraft such as the Seafire.

Nevertheless their seaworthiness was never called into question and they rode through - and operated in - some of the worst weather of the war. HMS Victorious' successful torpedo strike against Bismarck being a case in point.

Their distinctive hurricane bows proved particularly effective and became a feature of almost all subsequent aircraft carrier designs.

Eyewitness account: Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George V off Sakishima Gunto, 1945).

The weather was calm with almost no wind or sea, only the ever present Pacific swell. The fleet increased speed to 26 knots and turned into the swell to launch our aircraft. It was a beautiful finale to the exercises. The battleships pushed through the sea with obvious power while the cruisers cut gracefully through the brilliant blue water. Each time the battleships and cruisers pitched into a large swell, a huge bow wave rose level with their forecastles and the sea shot like a geyser out of their hawse pipes. The carriers, with their much greater freeboard and a bow that flared to the width of their flight deck, plunged into a trough and, with the sea often level with their flight deck, sent a huge plume of water flying forward and either side of the bow. The tremendous lift generated by driving such a large bow deep into an oncoming swell resulted in the bow rising rapidly, and frequently, the carrier’s forefoot came clear of the water. Timing the launching of aircraft under these conditions was an exacting task. The aircraft began to move down the flight deck as the bow reached the end of its downward plunge. If the timing was right, the spray had cleared and the bow was rising clear of the water when the aircraft reached the forward end of the flight deck and took off. Occasionally, an aircraft got out of sync with the ship and by the time it reached the end of the flight deck, the bow was buried in the oncoming swell. It was a tense moment, but in most cases, to everyone’s relief, the aircraft appeared safely out of the cloud of spray.

“With every man concerned doing his job efficiently and with squadrons at peak performance, aircraft in our ship could take off at intervals of 12 seconds and land at the incredible rate of one aircraft every 22 seconds”

Air Group

Britain initially operated squadrons of an optimal twelve aircraft, divided into four “sections” of three aircraft. Each “section” had a designated colour and each section aircraft a number.

Illustrious was designed with stowage allocated for 33 aircraft. Many reports state this was 36 or 32, but a look at the original lash-down arrangements shows provision for 12 aircraft in hangars A and C (named divisions of the one hangar space based on the fire curtain compartments), and 9 in Hangar B.

In the late 1930s, The Illustrious’ US contemporary, USS Enterprise, was carrying more than 70, and Japan's Akagi, 90.

At first glance, these figures can be misleading.

British standard aircraft capacity designations account only for numbers of operational aircraft capable of being stowed in hangars under peacetime conditions. The United States have always counted deck-parks (and sometimes disassembled spares) as part of their standard complement

This was based on differences in doctrine: The RN relied on a world-wide network of bases to resupply and repair its aircraft, as well as 'aircraft auxiliaries' such as HMS Unicorn. The USN operated its fleet carriers as stand-alone mobile airfields

For example: In 1942 HMS Victorious was deploying with 40 aircraft. About the same time it was recommended Yorktown operate 66 aircraft - though the number carried was 88 (including disassembled spares). Victorious soon after was was operating 51-58 machines while in company with USS Saratoga (where she would famously become known as "USS Robin").

Such lack of distinction between "operational" and "reserve/spare" aircraft is a cause of much confusion when it comes to comparing carrier air groups. Japan's Akagi and Kaga, for example, are regularly listed as capable of carrying 91 aircraft. But, in 1941, only 63 were operational aboard Akagi. Even Ark Royal - designed for Pacific operations - had a total stowage capacity of 72 aircraft (though 56 would be classified operational).

Also, many published "total" aircraft figures reference air groups carried in the 1930s when ships such as the Lexington could carry up to 120 of the smaller, lighter folding biplanes (78 of which were operational aircraft, the remaining 30 being "spares").

Like the US, Japanese reserve aircraft could be reactivated in a matter of days or hours and were such an integral part of operational planning that they were often tallied among squadron totals.

By 1941 US-style deck-parks were being introduced on the British carriers – as much because of the hurried adoption of non-folding Martlets, Hurricanes and Spitfires to the naval role as for any need to boost aircraft numbers.

In the late 1930s, tactical thinking had been that the armoured carriers should carry two strike squadrons of TSR (Torpedo Strike Reconnaissance) aircraft and a mixed squadron of six fighters and six fighter bombers.

This was because 1930s wargames - before the advent of radar - had generally demonstrated the worthlessness of carrier-borne fighters in the face of land-based opposition. Even against basic bomber formations, they simply could not respond fast enough to intercept before the ships in the fleet had been attacked.

The advent of radar changed this, dramatically.

Early war experience off Norway and in the Mediterranean quickly emphasised the practical role of fighters in fleet defence. They could be alerted before incoming aircraft were seen. They also could be directed to ideal attack positions in order to help overcome inherent weaknesses - such as a lack of speed or climb rate (problematic for the Skua and Fulmar).

As a result, the number of fighters carried began to creep up steadily until, in 1945, they formed on average more than two thirds of a carrier’s air wing.

But the problems related to the Illustrious class’ small aircraft capacity became obvious even before the first ship was completed. This was addressed with the modification of the fourth Illustrious Class vessel, Indomitable, while she was still in the builder’s yard.

The final two armoured carriers – laid down before the war but much delayed by political and supply issues during the early war years – were to emerge somewhat redesigned.

Nevertheless, the Illustrious, Formidable and Victorious had their aircraft load increased by 1942 by relaxing stowage spacing standards and adopting outrigger deck parks. These were essentially pylons upon which the tail wheel of a fighter could be suspended out over the side of the ship to keep the bulk of the aircraft off the busy deck.

Larger US-style permanent deck parks were being used by HMS Illustrious while operating with USS Saratoga in the Indian Ocean early in 1944.

With the adoption of deck parks came the need to constantly shift aircraft forward and aft to enable ongoing cycle of landing and takeoff operations. While this required larger deck handling parties, it allowed the Illustrious-class carriers’ air groups to be boosted to a much more useful 52-57 Corsairs and Avengers by 1945.

In 1944 HMS Illustrious had a total establishment force of 36 Corsairs and 27 Avengers allocated to (though not all were carried by) the ship. This allowed Illustrious to deploy on missions with either 36 Corsairs and 18 Avengers, or 27 Corsairs and 27 Avengers.

Despite US liaison officers repeatedly raising doubts about the capacity for the Illustrious class to launch a strike greater than 25 aircraft (some as late as 1945), HMS Illustrious - when carrying a force of 57 Corsairs and Barracudas - demonstrated her ability to launch 39 in a single range. Similar 'strike packages' would be launched by her sisters.

Air Group Evolution

HMS Illustrious: September 1940 to January 1941

* This conformed with the design specification, below-decks stowed, fire-safety spaced air group of 33 aircraft, rising to 41 for the strike against Taranto.

806 Squadron: 15 Fulmar MkI

816 Squadron: 9 Swordfish MkI

819 Squadron: 9 Swordfish MkI

+ 813 Squadron: 4 Swordfish, 2 Sea Gladiator (From Eagle for Taranto only)

+ 824 Squadron: 2 Swordfish (From Eagle for Taranto only)

HMS Formidable: March to May 1941

* Total of 41 aircraft

803 Squadron: 12 Fulmar

806 Squadron: 8 Fulmar

826 Squadron: 12 Albacore

829 Squadron: 9 Albacore & Swordfish

HMS Victorious: August 1941 to December 1942

* Total air group 33, reaching 35 with the temporary placement of two Martlets.

809 Squadron: 12 Fulmar

802B Flight: 2 Martlet III (September 1941 only)

817 Squadron: 9 Albacore

832 Squadron: 12 Albacore (Replaced by 832 Squadron from November 1941)

HMS Victorious: August 1942

* Total of 38 aircraft for Operation Pedestal

809 Squadron: 12 Fulmar

884 Squadron: 6 Fulmar

885 Squadron: 6 Sea Hurricane (outrigger park)

817 Squadron: 2 Albacore

832 Squadron: 12 Albacore

HMS Illustrious: February 1942 to August 1942

* Relaxation of stowage spacing standards allowed the carrier a total air group of 45 aircraft.

881 Squadron: 12 Martlet MkII

882 Squadron: 6 Martlet MkII

806 Squadron: 6 Fulmar MkII (Joined in May)

810 Squadron: 9 Swordfish MkI

829 Squadron: 12 Swordfish MkI

HMS Formidable: April 1942

* Total of 37 boosted to 49 for Indian Ocean ops.

888 Squadron: 16 Martlet

820 Squadron: 21 Albacore

+ 803 Squadron: 12 Fulmar (upon withdrawal to Bombay)

HMS Formidable: November 1942

*Total of 42 aircraft for Operation Torch, with Seafires on outriggers.

885 Squadron: 6 Seafire IIC (outrigger park)

888 Squadron: 12 Martlet II

893 Squadron: 12 Martlet IV

820 Squadron: 12 Albacore

HMS Illustrious: September 1942

* Total of 47 aircraft for occupation of Majunga and Tamatave

806 Squadron: 6 Fulmar II

881 Squadron: 23 Martlet II

810 Squadron: 9 Swordfish

829 Squadron: 9 Swordfish

From the Royal Navy's Aircraft Carrier Handbook 1943, courtesy Dr Alexander Clarke. Configuration shows Albacores/Swordfish and Martlets.

HMS Illustrious: September 1942 to February 1943

* The air group underwent a rationalisation of squadrons, but 46 aircraft were carried.

881 Squadron: 25 Martlet MkII

806 Squadron: 6 Fulmar MkII

810 Squadron: 15 Swordfish MkI

HMS Victorious: May to July 1943

* A total of 51 aircraft while deployed with USS Saratoga as part of Task Group 36.6 off the Solomons.

882 Squadron: 12 Wildcat IV

896 Squadron: 12 Wildcat IV

898 Squadron: 12 Wildcat IV

832 Squadron: 15 Tarpon (Avenger TBF-1)

*In June, Victorious embarked 22 of Saratoga's VF-5 F4F-4s for a total of 58 fighters and acted as the fleet's "fighter carrier" due to her superior direction capabilities. Saratoga, retaining 12 F4Fs for CAP, added Victorious' 15 Avengers to her own force of 37 SBD-3 and 16 TBF-1.

Seafires on outriggers aboard HMS FORMIDABLE in 1943

HMS Formidable: July 1943

* Total of 45 for Operation Huskey

885 Squadron: 5 Seafire IIC (outrigger park)

888 Squadron: 14 Martlet IV

893 Squadron: 14 Martlet IV

820 Squadron: 12 Albacore

HMS Illustrious: July 1943 to October 1943

* The introduction of a full deck park of Seafires boosted the fighter complement, but the adoption of the larger Barracuda reduced the TBD capacity. The total air group was 50.

878 Squadron: 14 Martlet IV

890 Squadron: 14 Martlet IV

894 Squadron: 10 Seafire IIC (deck and outrigger park)

810 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

HMS Formidable: September 1943

* Total of 49 for Operation Avalanche

885 Squadron: 5 Seafire IIC (outrigger park)

888 Squadron: 16 Martlet IV

893 Squadron: 16 Martlet IV

820 Squadron: 12 Albacore

HMS Illustrious: December 1943 to July 1944

* A review of aircraft types saw a new air group of 49 Corsairs and Barracudas activated. This would increase to 54 when one of the Barracuda squadrons would be swapped with a third Corsair squadron.

1830 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

1833 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

810 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

847 Squadron: 9 Barracuda II (Replaced by 1837 Squadron's 14 Corsair IIs in June)

- The air group was modified in May 1944 when the 21 Barracuda IIs were landed and exchanged for 18 Avenger Is for a two month operation in concert with the USS Saratoga (51 F6F-3, 24 SBD-5,18 TBF-1 - "spares" component unknown).

HMS Victorious: April 1944

* Air group of 46 aircraft for Operation Tungsten

1834 Squadron: 14 Corsair

1836 Squadron: 14 Corsair

827 Squadron: 9 Barracuda II

831 Squadron: 9 Barracuda II

HMS Formidable July 1944

* Air group of 42 aircraft for Operation Mascot

1841 Squadron: 18 Corsair

827 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

830 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

HMS Victorious: August 1944

* Air group of 50 aircraft for strike on Emmeahaven and Indaroeng

1834 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

1836 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

822 Squadron: 22 Barracuda

HMS Formidable August 1944

* Air group of 56 aircraft for Operation Goodwood

1841 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

1842 Squadron: 14 Corsair II

826 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

828 Squadron: 12 Barracuda II

HMS Illustrious: December 1944 to May 1945

* The extended deployment conditions of operating in the British Pacific Fleet saw a further reshaping of the air group. Now Illustrious would carry 57 machines.

1830 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

1833 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

854 Squadron: 21 Avenger II (This was reduced to 16 in March to allow more space for spares and reserve aircrew during Operation ICEBERG)

HMS Victorious: January 1945

* Air group of 53 for strike against Pangkalan Brandon

1834 Squadron: 16 Corsair II

1836 Squadron: 16 Corsair II

849 Squadron: 21 Avenger II

HMS Victorious: January 1945

* Total of 57 aircraft for Operation Meridian

1834 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

1836 Squadron: 16 Corsair II

849 Squadron: 21 Avenger II

Ship's flight: 2 Walrus ASR

HMS Illustrious: April 1945

* Total of 52 aircraft for Operation Iceberg

1830 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

1833 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

854 Squadron: 16 Avenger II

HMS Victorious: April 1945

* Total of 53 aircraft for Operation Iceberg

1843 Squadron: 19 Corsair II

1836 Squadron: 18 Corsair II

849 Squadron: 14 Avenger II

Ship's flight: 2 Walrus ASR

HMS Formidable: April 1945

* Total of 54 aircraft for Operation Iceberg

1841 Squadron: 18 Corsair IV

1842 Squadron: 18 Corsair IV

848 Squadron: 18 Avenger II

HMS Formidable: As part of Task Force 37 off Japan in August 1945

* 55 aircraft.

1841 Squadron: 19 Corsair IV

1842 Squadron: 18 Corsair IV

6 Hellcats (night fighter detachment)

848 Squadron: 12 Avengers

HMS Victorious: As part of Task Force 37 off Japan in August 1945

* 55 aircraft

1834 Squadron: 19 Corsairs

1836 Squadron: 18 Corsairs

849 Squadron: 16 Avengers

Ship's flight: 2 Walrus ASR

ILLUSTRIOUS class 'Batch One' key identifying features: Low freeboard, large flight deck round-down at rear (early war years) Two Pom-Pom mounts forward and rear of island (early to mid-war years). Two narrow lifts.

“To feel the great ship’s movement underfoot again; to ride with her majestic heel to starboard as the wheel went over as she passed the boom; and to stand on the quarter-deck watching the awesome wall of water mount higher and ever higher as she worked up to 20 knots— there was a wonderful exhilaration to all this, impossible to describe to those who have never gone down to the sea in ships. She had life and we were lucky to be part of it.

”