AT 0600 on May 3, Task Force 57 made its first rendezvous with the Logistic Support Group at supply point Mosquito. The cruisers and destroyers immediately set about topping up with fuel.

It was an incident-filled operation.

First the cruister Uganda tangled a fuel hose around a propeller. Divers had to be sent into the water to remove it.

Then an Avenger of 820 Squadron accidentally fired 100 rounds from its forward-facing guns while on Indefatigable’s flight deck. Several of these rounds struck a Firefly ranged on the deck. Two pilots of 1770 Squadron were wounded and an observer killed. Two ships’ officers in their cabins on Indefatigable’s quarterdeck were also injured.

The news, however, was not all bad. Reports of the deaths of Hitler and Goebells was flashed around the fleet.

By 1530 the Task Force once again was sailing towards Sakishima Gunto.

May 4

With Ishigaki and Miyako again just over the horizon, the first CAP fighters were sent into the air at 0540. The task force was holding position some 75 miles south of Miyako Shima.

Radar reports indicated the Japanese had upped their activity levels since the BPF had departed.

No sooner had the fighters taken to the air than the fleet’s air warning radars began to detect contacts over the islands.

The first bogey was reported at 0545, and many more would be made that day. Another contact – flying too high for the CAP – was engaged by radar-controlled heavy anti-aircraft artillery. It escaped untouched, and the fleet had to assume its position had been exposed.

One formation soon approached the British ships. Two “rookie” Hellcats from Indomitable on the CAP was quickly vectored towards the small group of Zekes, of which one was shot down. It was their first operational flight.

Task Force 57 went to flying stations at 0605. Two strikes comprising a total of 47 Avengers and Fireflies were put into the air. The first had the airfields of Miyako as their target. A second strike, destined for Ishigaki and Miyara, commenced at 0815.

It was a particularly clear day, and the flak over the airfields especially intense. An 858 Squadron Avenger was hit and sent into the sea after attacking Miyara. The remaining strike aircraft returned after cratering the runway at 0830.

The morning’s events had confirmed in Admiral Rawlings mind an idea that had been forming since before ICEBERG. He was well aware of how quickly the 500lb and 1000lb bomb craters on the coral airfields were being filled-in. He was also aware of how limited these bombs were against dug-in emplacements.

He resolved to change tactics and add shore bombardment by the battleships and cruisers to the selection of strike power. Rawlings felt that heavy shells with air-burst settings would be particularly useful. The bombardment would not only deliver more effective ordnance on the dug-in Japanese anti-aircraft guns, it would relieve the boredom among the big warships’ crew. While the carrier crews were constantly run off their feet, the battleships and cruisers in particular had little to do all day except sit at action station and watch the skies.

Rawlings knew the fleet had been detected. But it’s position had been known to the enemy for most of the previous strikes. Why should today be any different?

Admiral Vian agreed.

It would prove to be the British Admirals’ only significant error in judgement.

The battleships HMS King George V and Howe, along with the six-inch cruisers HMS Swiftsure, Gambia and Unganda, as well as the anti-aircraft cruisers HMS Black Prince and Euryalus, separated from the carrier formation at 1000. The 25th Destroyer Flotilla’s six ships accompanied as escort.

Journalist David Divine was aboard HMS King George V

“I was with Rawlings that awful morning when the carriers were attacked, when he had left the carriers to go into the Sakishima Gunto for a bombardment, which was really a morale builder and nothing else. It was a misjudgement. He reckoned there was no further possibility of kamikaze attack. So we left the carriers without the artillery umbrella, went in, conducted the bombardment. As we turned on the bombardment run, I was sweeping the horizon on the starboard quarter and I saw a dirty great mushroom of blue smoke and that was the first of the kamikaze hits. I was actually standing next to the Flag Lieutenant when the first hit took place. Rawlings came out from behind the screen almost immediately afterwards and joined us. Rawlings was in a considerable state. There he was and there they were, being hit, and he wasn’t there. He was very sober and very quiet about it, but you could see he ws deeply moved by the whole thing. So was I.”

Admiral Vian, knowing his carrier force was under-protected, ordered his ships to huddle together. The eight remaining destroyers were positioned to give the maximum possible AA coverage: Two were set at equal intervals between each carrier and on the line between each adjacent carrier.

Admiral Vian would later write:

“I was not sufficiently alive to the effect on our defensive system which would be caused by the temporary absence of the radar sets and anti-aircraft armament of the battleships. The Japanese were.”

The bombardment force powered towards the Miyako Shima at 24 knots, with its own CAP cover of fighters also intended to offer fall-of-shot spotting reports.

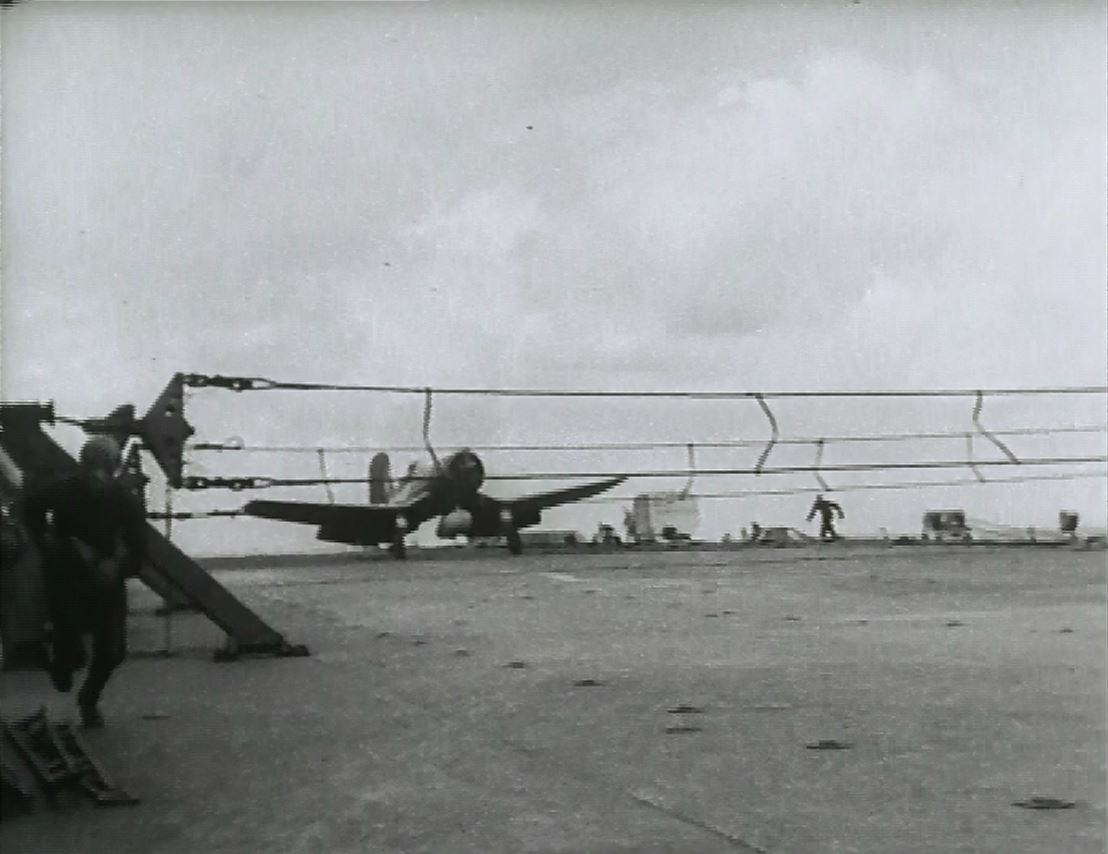

Footage showing the British Pacific Fleet off Sakishima Gunto. Clips include the kamikaze swooping on Formidable, before coming about for its second - successful - attack run. Another clip shows an Avenger being rolled off the side of the burning Formidable. Other footage includes a kamikaze striking Indomitable's deck..

By 1155 the battleships and cruisers had taken up bombardment lines some eight miles off the south coast of the island, steaming at a steady 15 knots. The fleet opened fire at 1205. The battleships smashed Hirara airfield. Their big 14in shells were being lobbed from 25,000 yards, while the cruisers moved closer inshore to 18,000 yards to attack Nobara and Sukhama airstrips.

No sooner had the first broadsides been sent on their way than a “flash” message came through to Admiral Rawlings from Admiral Vian: The carriers were under attack.

The officers and crews of the big-gun ships would soon see a large blue-black smoke plume rising from the direction of the carriers they’d left behind. They’d quickly learn that HMS Formidable had been hit, and hit hard.

Rawlings could only watch the distant billowing plumes and order the bombardment rate be sped up.

King George V’s salvos were said to be “always just missing” by her spotter. Photographs later proved that Howe was more successful: her target area had been peppered with hits.

Inshore Euryalus and Black Prince fired their air-burst ammunition over Nobara’s AA batteries. Swiftsure and Gambia, positioned three miles off King George V’s port quarter, sent their 6-in shells at Nobara’s airstrip. Uganda had Sukhama airstrip to herself.

King George V fired 77 14in shells and 188 5.25in rounds; while Howe fired 118 14in shells and 190 5.25in rounds. The cruisers fired 598 rounds of 6in and 378 of 5.25in,

At 1247, the bombardment force changed course back south towards the carriers at 25 knots.

Eyewitness account: Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George V)

“A” turret fired four ranging-rounds, all of which we could see strike the island, a tall column of black smoke and dust marking their impact on a distant hill. The three 6-inch gun cruisers ahead of us were an impressive sight, firing rapidly at the island’s anti-aircraft installations. However, the necessity to take cover when the 14-inch guns fired, quickly overcame any interest I had in watching the cruisers, or our own shells striking the island. Anyone on the ADP who could, crouched behind the outboard bulwark or any other shelter on our open platform and concentrated on listening for the “ting-ting” of the fire-gong in the main director, which sat in the middle of the ADP My action station was at the base of its supporting tower; the director was immediately above me. The fire-gong preceded the firing of the 14 -inch by a second or two, and that was just enough time to crouch down on the deck and shield yourself from the blast of the guns. We were only a few minutes into our bombardment, when we lost communication with our spotting aircraft, but in spite of this, the shooting was good. For 50 minutes , the two battleships battered the airfields with their 3/ 4 ton, high explosive 14-inch shells. Reconnaissance photographs of the target area after the bombardment confirmed the severe damage that the lethal 14-inch shells had inflicted on the runways, parked aircraft, and airfield installations. The communication trouble we were having with our aircraft was in our own VHF and HF sets. The problem persisted and before long, we had to turn control of our CAP over to Howe.

These were minor problems compared to the ones that struck the carriers shortly after we left.

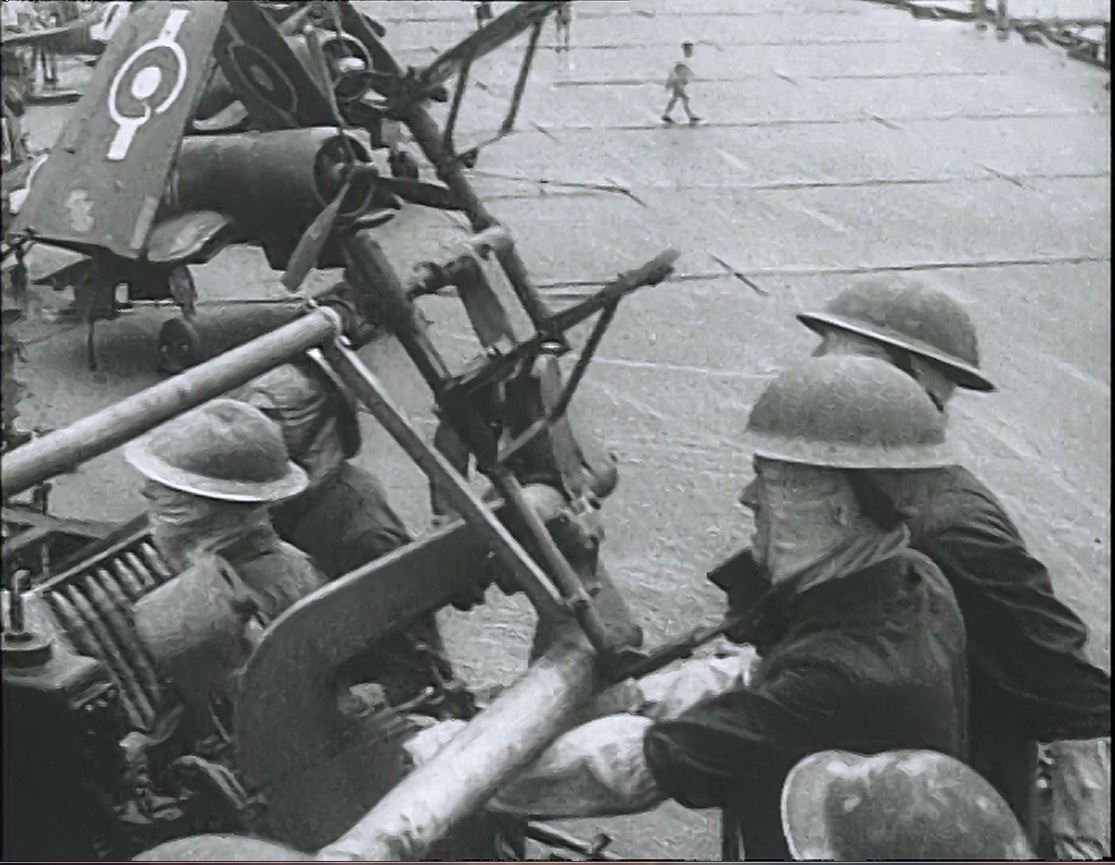

Seafires aboard HMS INDEFATIGABLE, identifiable by the "slipper" style conformal fuel tanks under the fuselage.

Meanwhile, the air strike by aircraft cobbled together from Formosa’s 8th Air Division had made its mark on the carrier force. Some 26 aircraft based out of Giran, Formosa had taken to the air, comprising decoys, kamikazes, escorts and controlling “Gestapo” aircraft.

It was a carefully coordinated and determined kamikaze attack.

At 1102, little more than an hour after the heavy ships had left Task Force 57’s screen, the first of these “bogey’s” began to appear around the carriers. They were plotted to be some 50 miles to the west and closing.

At 1104, a second group was detected to the south.

Shortly later, a third was seen approaching at 66 miles.

Then a fourth appeared on the radar screens.

This distribution of groups was to overwhelm the carriers’ radar offices. Each ship had to manually direct its radar sets to determine the range and height of specific targets. In doing this, the movement and approach of other groups of “bogies” was left unseen.

The southern group became the main cause of concern for the Fighter Direction Officers which sent their CAP fighters after it. This quickly proved to be a decoy once the CAP Seafires arrived, followed shortly after by several Corsairs.

The first effective interception was made at 1120 when the Seafires - including Sub lietenant RH Reynolds - shot down a “Hamp” (an older version of the Zero than the usual “Zeke” model encountered off Sakishima).

At 1125, CAP Corsairs engaged the third group of bogies. These turned out to be Zekes, but the Corsairs were only able to shoot down one before losing sight of the remaining three.

This was to be an unfortunate situation. The Zekes were kamikazes and the three survivors were able to make it all the way to the huddle of carriers and destroyers before being spotted again.

The total number of attacking aircraft is uncertain, but it seems only 10 of the roughly 26 attackers were kamikazes. The Japanese had pressed home their attacks with unexpected skill and resolve. The pilots had made clever use of the available cloud and the “Gestapo” controllers had effectively confused the reduced number of radar sets by their force dispersion, decoys and regular change of heights.

As a result, the harried carrier radar operators lost track of the approaching kamikazes.

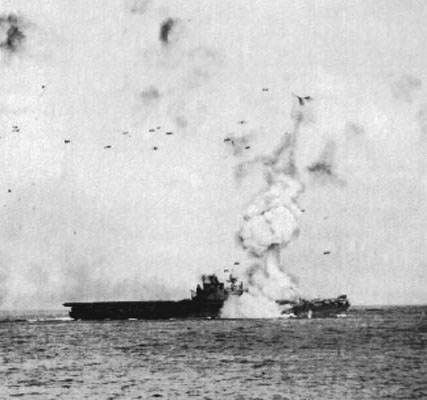

This composite image shows HMS FORMIDABLE'S flight deck after the kamikaze attack of May 4.

The first flight of Zekes had approached the task force at a very low level and had only climbed steeply to attack height when some 15 miles from the formation.

The carriers had no contacts on their screens within a 20 mile radius at 1131 when several aircraft were seen diving out of the clouds at 3000ft. These kamikaze aircraft drove at full power towards the armoured carriers.

The book Send her Victorious contains this account of the attack:

“Analysis now shows that this group escaped detection, either because the few radar sets in the ships were busily tracking the decoys, or else because the enemy made a low approach at sea level before climbing very high at about 15 miles range. Whatever the cause the effect was very frightening to the spectators on the flight deck of Formidable….”

Admiral Vian would later concede that the Japanese had bested his command that day:

“The first knowledge we had of their presence was when one of them was seen diving from a height straight down on Formidable.”

A large flash was followed by billowing black smoke from HMS Formidable's decks.

HMS Indomitable, Admiral Vian’s flagship, would report a kamikaze had skidded across the flight deck and caused only minimal damage. The damage was so light that the Admiral reportedly had no idea the carrier had been hit until someone told him.

Despite the damage to the two carriers – and in particular their radar sets – the task force fighter controllers managed to maintain an effective CAP operation.

At 1220 a Jill was intercepted and shot down by Indomitable’s Hellcats. At 1252 a Val was brought down by two of Indefatigable’s Seafires.

Admiral Rawling’s force of battleships and cruisers rejoined the carriers at 1420. By this time most of the mess on the carriers had been cleaned up. Formidable’s flight deck was operational once again by sunset. She was able to land-on 13 of her Corsairs at 1700. Indomitable’s air operations had hardly been delayed.

The return of the big-gun ships, however, restored the full strength of Task Force 57’s radar and anti-aircraft gunnery coverage.

Task Force 57 would withdraw early that afternoon to lick its wounds at a safe distance to the south-east.

The Japanese attacks would continue, however.

At 1515, Victorious’ Corsairs caught and shot down a Judy. Lieutenant D.J. Sheppard claimed this as his fifth kill, making him the FAA’s first Pacific fighter ace.

The fleet was withdrawing when another large attack developed.

At 1721 a Judy – possibly the kamikaze strike force’s “Gestapo” directing aircraft – was splashed from 24000ft. The lack of guidance made the remaining kamikaze’s easier targets. Indefatigable’s Seafires caught a flight of four Zekes a few minutes later and succeeded in shooting down three.

Friend or foe identification yet again proved to be lacking: HMS Formidable’s understandably jumpy air-defence crew opened fire upon a battle-damaged Hellcat which was returning for an emergency landing.

The pilot, fortunately, escaped and was picked up by the destroyer Undaunted.

The final action for the day happened at 1820 when a Corsair from Victorious was vectored on to a “bogey” by fighter controllers and shot down a Zeke.

By the end of the day, 11 aircraft were claimed as shot down by Fleet Air Arm fighters. Two more had been claimed by the fleet’s guns.

The FAA had also lost 13 aircraft – 11 on the decks of Formidable. One Hellcat had also been shot down by Formidable’s jumpy gunners. An Avenger had been shot down by Japanese flak over Miyako.

The attack on the BPF had coincided with another massed attack on the US 5th Fleet. The fifth kikusui of 125 suicide aircraft was timed to cover a major land-based counter-attack on Okinawa.

Captain Charles Hughes-Hallett,

Commanding Officer, HMS Implacable:The American carriers didn’t (have armoured flight decks) in those days; they had the ordinary light wooden deck, the reason they never followed our pattern being that , in hot weather, waltzing about on 3.75in of steel gets very bad on the feet. We reckoned that the maximum heat time occurred about three to four in the afternoon, and so my Commander Air amused himself one day by breaking an egg on the flight deck at that time. It was lightly fried – not really to edible condition – in 7.5 minutes; and that is what you had to walk about on. But the result was that when a kamikaze hit an American carrier, it was a three months’ dockyard job; in the case of hitting a British carrier, you took a couple of brooms and swept the rubbish over the side. A great friend of mine, an ex-pilot who was liaison at the American headquarters in Honolulu told me that at a daily staff meeting one morning the first kamikaze attack on a British carrier – the Formidable – was reported. The end of her signal said: Expect to be back in action again by four o’clock in the afternoon.” The American staff around the table more or less lay back and roared with laughter, saying “Those British again!” Next morning, when they heard she was back in action at four o’clock in the afternoon, they changed their tune rather rapidly.”

All that remains of a burnt-out Corsair aboard HMS FORMIDABLE.

Steel decks spared lives, and so did razor blades

MELBOURNE, 1995: Both the weaknesses and the strength of the British carriers became obvious to me on May 4, 1945, when a Japanese fighter, one of a force of more than 120 planes committed to suicide attacks that day, roared low over HMS Formidable.

The pilot was superb. As I watched from the flight deck of the British carrier, he threw the Zero into a vertical climb. At about 500 feet, it banked sharply and dived toward us. The plane and its bomb exploded in the middle of the flight deck, about 30 feet from where I crouched behind thick armor plating.

Thanks to that plating, our casualties were light, nine killed and 50 injured. All planes parked on the deck were destroyed. But within two hours, the hole in the steel plating made by the bomb had been filled in and aircraft that had been aloft at the time of the attack were able to land.

That would have been unlikely on the much more vulnerable American carriers. But what happened later that day on the Formidable would not have happened on a well- equipped American warship, either.

In the evening, Lieutenant Commander Benjamin Van Doren Hedges, U.S. liaison officer aboard the Formidable, walked into the hospital. “Can you use a hand, Doc?” he asked. The ship’s doctor, an elderly reservist, had been unable to cope. Not long afterward, a destroyer carried Commander J. Steele-Perkins, the British fleet surgeon, alongside.

He had not brought a medical kit, assuming that there would be one aboard. Instead he found that the scalpels were blunt, rusted and unusable. Commander Hedges fetched a supply of razor blades. Breaking one of them in two, he clasped one half in a pair of forceps, sterilized the instrument and handed it to Commander Steele-Perkins. “Here’s your scalpel,” he said.

As a blade became blunt, another was inserted and sterilized. “There’s been a doctor in my family continuously for more than 150 years, but I bet even the first one didn’t have to operate under these conditions,” Commander Steele-Perkins said after he finished the surgery.

Four days later, the Formidable was hit again by a kamikaze bomber in the center of flight deck. There were fears that the carrier might break in two.

However, it was still in action at the end of the war, an impressive reminder that whatever other weaknesses the ships of the Royal Navy might have had, the armored flight deck was an effective last line of defense.

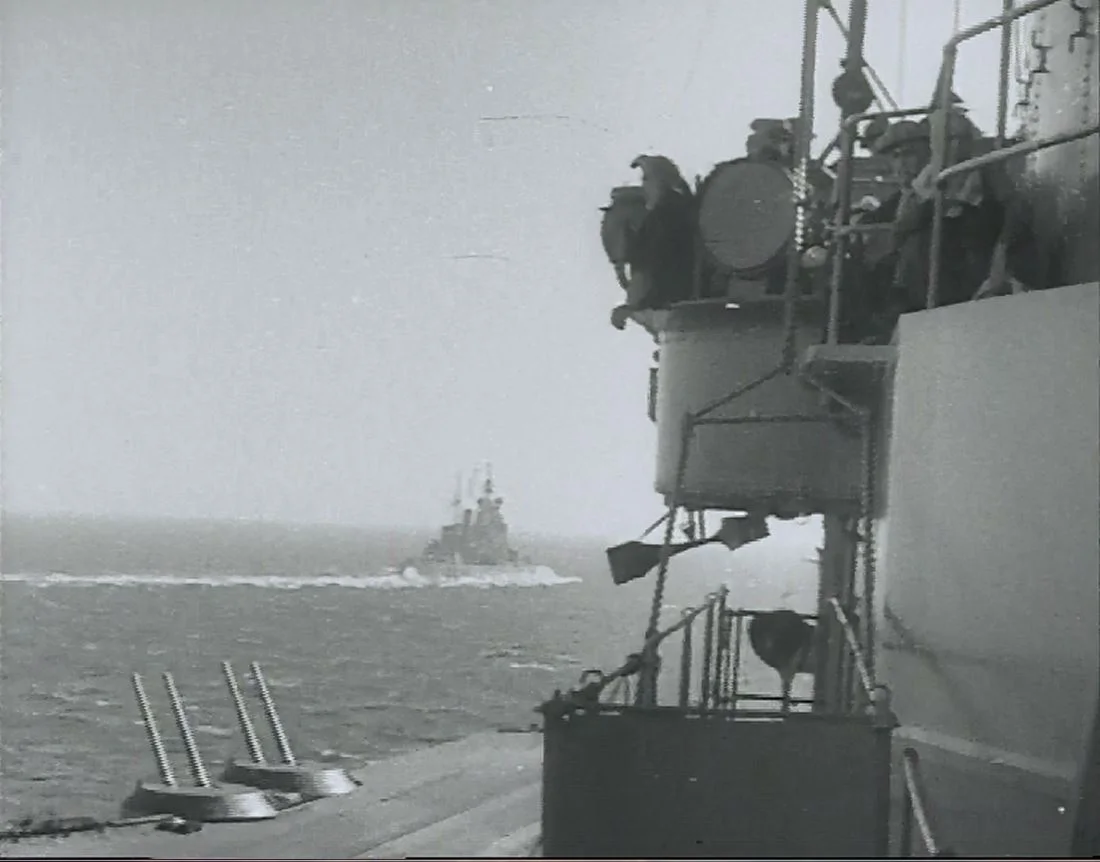

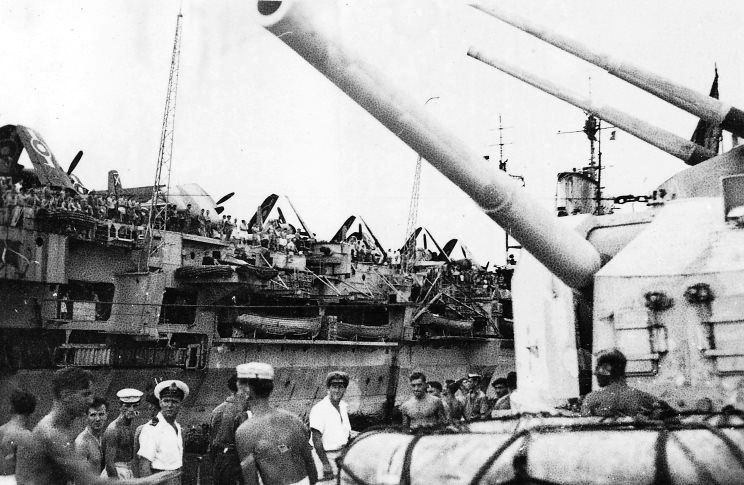

Avengers fly above the British Pacific Fleet. In the foreground is HMS KING GEORGE V or HOWE.

May 5

By morning HMS Formidable was operating at full speed once again.

The routine of air strikes continued largely unaffected by the previous day’s kamikaze attacks.

Admiral Rawling’s received some consolation for the split-fleet debacle: The Avengers and Fireflies reported encountering no flak over Miyako. The battleships' 14-inch shells had done their job.

Ishigaki and Miyako were once again bombed and left unable to operate aircraft. Three aircraft were claimed destroyed on the ground.

0730 a hostile reconnaissance aircraft was detected by radar and CAP fighters vectored to intercept At 0920 the Japanese aircraft, a Zeke, was shot down at 30,000 feet after a 300 mile chase that had lasted 108 minutes. The flight of four of Formidable’s Corsairs was rewarded with a “what a splash” message from Admiral Vian.

Among the successful Corsairs were two of Formidable’s brood that had taken off from their overnight refuge aboard HMS Victorious.

A Corsair and two Seafires were lost to accidents, however.

The last mission of the day was to fly off journalist David Divine and Captain Anthony Kimmins, Task Force 57’s press contingent. They were to land on what was supposed to be a secured airfields in the midst of an intense Japanese counter-attack.

Nevertheless, they, with their reports and photographs, began the long journey back to Australia.

After the day’s operations, the BPF withdrew towards replenishment area “Cootie”. The USN escort carriers of TG52.1 moved towards Sakishima Gunto to take TF57's place.

May 6-7

During the replenishment period HMS Formidable’s damage control teams worked further on the patch in the armoured deck to smooth out the depression for easier flying operations. They also succeeded in restoring the after crash barrier to full service.

As his ships refuelled and restocked, Admiral Rawlings formally reviewed his Task Forces’ tactics.

The 5.25in cruisers would now stay with the carriers to lend their specialist anti-aircraft services. Future bombardment runs would see the carriers closing to just outside radar range of the shore to remain close to the massed artillery of the big-gun ships.

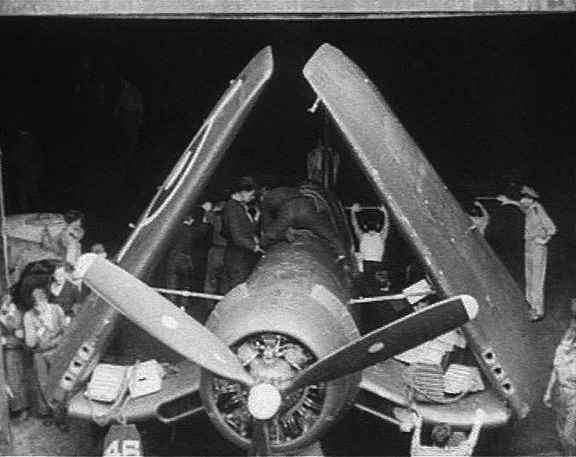

Corsairs arrayed on the deck of HMS FORMIDABLE - identifiable by her distinctive radar mast protruding onto the deck...

May 8

As dawn broke, Task Force 57 was once again in position to launch its now almost routine strikes against the airfields of Sakishima Gunto.

The TarCAPS found it difficult to find their stations amid the heavy cloud. The whole area was affected by heavy weather, so the day’s strike operations were cancelled. Air strikes by Avengers and Fireflies were also abandoned.

The weather was so poor Admiral Rawlings was unable to initiate his modified plan for another heavy ship bombardment of the airstrips.

The fleet and TarCAP fighters were launched, however, and kept up operations throughout the day.

By the time the CAP was were recalled at 1900 the gloom was so heavy that the carriers had to beam their searchlights up into the clouds to lead their chicks home in the thick evening haze. After an anxious wait amid driving rain and near zero visibility, the last fighters finally landed on.

As night fell, the BPF steamed west in search of clearer conditions.

Anti-Hawk Stations

To reduce the potential of damage from kamikaze attacks, the British carriers had been instructed to adopt a specific set of precautions. When the “flash” alarm of an imminent kamikaze attack was received, both lifts were to be raised and sealed, the armoured airlock doors to the hangar locked and specialist flight deck firefighting parties formed in the relative protection of the gallery deck, beneath the armour but with access to the flight deck via the various sponsons jutting from the side of the ship. Their fire fighting equipment was similarly set up in this protected environment, but ready to be quickly unravelled to fight fires among the flammable aircraft on the steel deck. A large number of “Squadron Action Gangs” were set up around the edges of the flight deck. These men were to assist in moving aircraft or assisting damage control teams – whichever was judged most necessary at the time.

A composite of two photographs showing the deck of HMS FORMIDABLE on May 9

May 9

With Britain celebrating news of complete victory in Europe, the British Pacific Fleet again found itself confronted by kamikazes.

The TarCAP arrived over Sakishima Gunto shortly after dawn and reported improved weather.

The routine four strikes were launched by the FAA against the two main Sakishima islands. The 73 Avengers and Fireflies with their escort succeeded in blasting all the runways yet again. One Avenger of 1834 Squadron failed to return, its crew declared missing, presumed dead.

At 1145 a high-level “snooper” was detected by the fleet’s radars when it was about 30 miles from the formation. The CAP was able to scare it off, but was unable to obtain sufficient height in time to make a kill.

The outcome should have been expected.

At 1645 the number of “bogies” on radar screens began to mount rapidly. At first a group of four fast-moving contacts was narrowed down to a very low altitude at a range of 28 miles to the west. It was an inopportune time as the task force was recovering aircraft.

Four Seafires made a successful interception six minutes later while just 15 miles from the fleet. The pilots of the nimble interceptors allowed themselves to lose tactical awareness and crowded around a single Zeke, shooting it down. But the remaining three were left to continue their way towards the fleet.

Admiral Vian would later comment:

“Their foolishness… was to cost the fleet dear.”

The remaining three Zekes dodged a second group of CAP Seafires at 1650 and hurtled towards the carriers.

The task force was manouvering constantly at 22 knots. Shortly after a 60 degree turn to starboard was initiated, a Zeke was spotted making a shallow 10 degree dive towards Victorious from the starboard quarter.

WITNESS ACOUNT: HMS FORMIDABLE, MAY 9

Extract from “Alarm Starboard”,

Lt Cmdr G. BrookeThere was nothing to do now but watch and wait. As a terror weapon these kamikazes were unsurpassed. It was a sensation of ‘the full twitch’ as Air Branch had it, especially on a cloudy day, after perhaps ten minutes of a broadcast running commentary on the steady approach of a formation to heat the dry announcement, ‘They have split up now and are too close for radar detection’. Everyone who has to stay in the open searches the sky with his neck on a swivel, light weapons traversing back and forth, up and down in amplification of the Gunner’s nerves. There is not a man, streaming with sweat under his protective clothing (flame-proof balaclava, gloves, goggles and overall suit with stocking, not to mention tin hat) whose hands have not discovered some piece of equipment that needs last minute adjustment. When at last you see him and all the guns are blazing it’s not so bad, but there is still something unearthly about an approaching aircraft whose pilot is bent on diving himself right on to the ship. Wherever you are he seems to be aiming straight for you personally, and in the case of those in or near the island, that’s just what he is doing. We had been searching the sky for some minutes when gunfire broke out to port. Victorious was firing and even as I looked there was an explosion on her flight deck. Moments later she opened up again and there was another attacker coming in from astern. It was streaming flames but kept going and also crashed on her flight deck.

Smoke was seen to billow from close to one of HMS Victorious’ forward 4.5in gun mounts, then another kamikaze would crash through her aft deck park.

At 1705, a fourth and final kamikaze flew into the fleet’s barrage, seemingly undecided as to its target. First it appeared to approach HMS Formidable. Then it swung towards HMS Indomitable. Both carriers made hard turns to evade its attack runs. The kamikaze then banked back towards HMS Formidable and plunged in to her rear deck park. Once again, the armoured carrier was enveloped in smoke and flames.

Task Force 57 held its collective breath: The fireball and smoke plume seemed even more intense than that of May 4. But, within 15 minutes, the flames were doused and wrecked aircraft began being tossed over the side. After 35 minutes, aircraft began flying operations from Formidable's deck once again.

Casualties were surprisingly light. Only one had been killed aboard HMS Formidable, and three aboard Victorious.

HMS Victorious had not ceased flight operations at all during the attacks.

Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George V)

The day’s strikes had gone without incident, when at 1730, our Sea-guard radar picked up a bogey 30 miles from the fleet. None of the other ships’ radar held this contact and the next several minutes were spent confirming the nature of the contact. They were flying very low to stay under our radar. By the time the information reached the ADP the bogey was classified as four-plus aircraft now 25 miles away and closing fast. Our fighters were vectored to intercept them, and as they did so, 17 miles from the fleet, the Japanese climbed rapidly and split up. Estimating height by radar was imprecise and this tactic made the interception more difficult. One Zeke was sighted and shot down. The other aircraft were lost in the cloud and faded from our radar screen at seven miles. All eyes were rivet-ted on the low cloud, straining to see any sign of an aircraft. Suddenly, a plane shot out of the cloud on our starboard bow, wheeled as it dived and crashed on Victorious’s bow ...

The exact number of planes in the raid was an estimate, and now that they were overhead and inside our radar detection area, the only way to confirm their presence or absence was visually. The thick cloud over the fleet made it very difficult for our CAP to be sure that the area was clear of kamikazes. The CAP continued to search the sky and the fleet watched the low cloud intently for any sign of aircraft. All guns were on lookout bearings and ready for instant action, but no more suicide planes attacked the fleet.

WITNESS ACOUNT: HMS FORMIDABLE, MAY 9

Extract from “Alarm Starboard”, Lt Cmdr G. BrookeEvidence of our second Japanese casualty was one eye, picked up by a rating with a strange sense of humour; it was put in a match-box which he would suddenly push open in front of unsuspecting messmates. We landed on a strike shortly afterwards - they had taken temporary refuge in Victorious - and continued much as if nothing had happened. Admiral Vian signaled WELL EXTINGUISHED. ANY FOAMITE LEFT? and it was gratifying to get from Uganda "OUR SINCEREST ADMIRATION". It was surprising to find that the crew of the pom-pom that had been engulfed in flames were quite all right; anti-flash gear was made of uncomfortably hot material but it was good to have such evidence of its efficiency. Not so reassuring was the plain fact that our pom-poms and Oerlikons simply did not have sufficient physical stopping power. Both our opponents were hard hit but came on, possibly aided by the freezing of control surfaces at high speed. The new Implacable had a quadruple Bofors gun of large calibre and we hoped for something similar when next in Sydney.

May 10 & 11

Admiral Rawlings informed TG52.1 that it would have to maintain station on Sakishima Gunto until May 12.

With only two of Task Force 57’s four carriers fully operational, the Admiral knew he needed at least three days to ensure repairs on Formidable and Victorious were carried out to an acceptable standard before effectively air operations could once again be conducted.

Fortunately casualties had been light. But the toll on aircraft over the previous two days had been high: One Corsair had been shot down and a further 17 destroyed in the kamikaze attacks. One Avenger had also fallen victim to the splinters and fires.

The Fleet Train escort carrier HMS Speaker was able to make good some of the losses. But not all.

Admiral Spruance was satisfied that the islands had been neutralised and signalled Rawlings that his fleet would no longer be needed to attack the airfields after May 25.

In the meantime, the RAMRODS and bomber raids would continue. The tired BPF pressed on.

On May 11, the BPF would learn of yet another kikusui attack

This time the flagship of Admiral Mitscher, USS Bunker Hill, had been hit by two kamikazes resulting in 392 killed and 264 wounded.

Despite being repaired, she would never return to full active service.

May 12

Before dawn Task Force 57 was in its new station 100 miles south-east of Miyako Shima. The radar pickets were established – with HMS Swifsture paired with Kempenfelt and Uganda with Wessex.

The CAP began to launch at 0540.

The schedule for the day was a familiar one: Fighters would maintain station over the islands, picket cruisers and the task force itself, and four strikes of Avengers and Fireflies would crater the runways and destroy targets of opportunity.

Reconnaissance revealed that several airfields on the islands were still serviceable, despite the best efforts of Task Group 52.1.3.

The usual four Avenger strikes were sent on their way, though this time three would focus their efforts on Miyako and one against Ishigaki. The FAA fighters, with little activity in the air, strafed the dispersal areas.

Two Avengers were hit by anti-aircraft gunfire but managed to limp out to sea where they ditched. The destroyer Kempenfelt rescued one crew after they were spotted by a Firefly, the USS Bluefish picked up the other. 1884 Squadron’s commanding officer was shot down and killed over Hirara airfield while strafing Japanese gun positions.

It had been a busy day for Task Force 57: The fleet’s reduced complement of Corsairs, Avengers, Hellcats and Fireflies flew a total of 99 offensive sorties. CAP and ASW patrols were maintained as per normal.

Waite Brooks, The British Pacific Fleet in World War II: An Eyewitness Account (aboard King George V)

The Japanese had a sophisticated intelligence gathering service that provided them with a comprehensive understanding of our operations, in attacking them and defending the fleet, and the success of their attacks against the fleet. They knew that the aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy had armoured flight decks, but how successful these would be in protecting carriers from kamikaze attacks was an unanswered question, until attacks had been made and the results could be assessed. They now had considerable material to analyze and the results were, that while the attacks were destructive, they had not put any of the Royal Navy carriers out of action. In general, the same attacks directed against the unarmoured decks of the American carriers were far more successful in removing a carrier temporarily or permanently from operations. It would appear that this analysis had considerable influence in their decision as to how to respond to our attacks.

May 13

Dawn broke to another fine day.

However, HMS Indefatigable would suffer an unusual attack – of gastro-enteritis. Some 55 pilots and observers were stricken with the bug, along with 27 of the carrier’s crew – including the whole fighter direction team. She still managed to launch 23 Avenger and six Firefly sorties, along with 48 Seafire CAP sorties.

The Sakishima Gunto airstrips were assessed as serviceable once again. Once again, four Avengers strikes were flown off from the BPF carriers.

Again, three were directed towards Miyako and one to Ishigaki. This time 102 sorties bombed the runways, barracks, buildings, barges and storage dumps. Attacks also were made on a newly discovered concealed dispersal area near Hirara.

One of Formidable’s Avengers had been heavily hit by anti-aircraft fire. Unable to land on his home ship, the pilot diverted to HMS Victorious. With no flaps and only one wheel extended, he put the aircraft down with a minimum of damage.

Slight variety was added to the days operations when three destroyers attacked a possible contact with depth-charges at 1203. Under a CAP of two Corsairs, the ships were joined by three Avengers. The contact was likely to have been a false echo.

The lack of Japanese submarine activity came as a surprise to the British fleet, which had grown used to the attentions of the German and Italian under-water forces in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Rear Admiral William Weston would comment:

“To me the most astonishing part of the whole operation was the complete failure of the enemy submarines to attack our oilers and fleet train, upon which everything depended. Whilst on passage a collection of slow but valuable repair and supply ships was wont to steam at 10 knots, screened by a half dozen small minesweepers. What would the U-boats have done to such a target.”

After the final CAP aircraft had landed on at 1920, the task force once again set course for the replenishment rendezvous “Cootie”.

USS Enterprise's forward lift is blasted high into the sky after the impact of a Kamikaze and its 550lb bomb.

Yet more bad news was to arrive from the US 5th Fleet: This time it was the famous USS Enterprise that had been wounded by the kamikaze scourge, as had the battleship New Mexico.

May 14

Task Force 57 and the Logistic Support Group once again made rendezvous in Area Cootie. A number of 1600lb bombs were transferred successfully by HMS Black Prince from HMS Formidable to Indefatigable. Due to a shortage of replacement general purpose bombs for all the carriers, the decision was made to mix Avenger and Corsair bombloads with semi-armour piercing weapons.

Admiral Rawlings took the time to contact Admiral Spruance, who revealed his intentions to keep the British armoured carriers close to the Japanese mainland from July. The success of the armoured flight deck had guaranteed the British Pacific Fleet’s carriers a central role in the final stages of the war on Japan – operation OLYMPIC.

Spruance signalled that Task Force 57 would be released from its role in ICEBERG from May 25. He stated his desire for the British to repair and reprovision in order to be ready well before the planned major push against the Home Islands in November.

The four active fleet carriers of the BPF in line-ahead formation.

May 16

The first of three strikes took to the air at 0540 and headed to the Miyako Jima airfields. Another two strikes were made against airfields in Ishigaki Jima.

While the Japanese air forces appeared to be withdrawing from the Sakishima Gunto region, the soldiers left behind to defend the airfields were no less vigorous. Gunfire succeeded in damaging several FAA aircraft.

A Corsair launches from HMS FORMIDABLE.

Nevertheless, the airfields, which had only been partially repaired during the replenishment period, were once again put completely out of action.

All of the airfields were already strewn with burnt-out aircraft and dummies. But they were cratered afresh, an ammunition dump was exploded on Miyako and four trucks full of Japanese troops strafed. A RAMROD of Corsairs from Victorious had spotted the troop convoy. All were strafed and set alight, and most of their troop passengers killed. But one Corsair was hit by rifle fire from the soldiers and was forced to ditch three miles off Miyako’s shore. USS Bluefish came close to the coast during the night to pull the pilot out of the water.

Two “Baka” suicide aircraft were spotted on the airfields. These were quickly attacked and destroyed. A cave was also seen to have been housing aircraft. It was bombed and at least five hits were observed. Oil dumps, vehicles and various barges and boats were also attacked.

While seven Japanese aircraft were claimed destroyed on the ground, the FAA lost four further aircraft in accidents.

On board a British Pacific fleet carrier operating against the Japanese. Lieutenant Commander (A) Freddy Charlton, British Fleet Air Arm pilot, had a remarkable escape when the long-range petrol tank of his Chance-Vought Corsair fighter burst into flames (seen here) as he landed on the deck of the aircraft carrier. Both pilot and plane escaped damage.

May 17

By first light the winds had failed to pick up to any appreciable extent. This was to prove an issue for HMS Indomitable which had had her speed reduced due to problems with her centre shaft.

HMS Victorious was also to find the light winds problematic: Her crash barriers were already jury-rigged after the kamikaze attacks and her flight-deck movements were slowed by the damaged forward lift motors.

A Corsair attempted an emergency landing on Victorious, but made its approach far too fast. When it hit the deck it ripped two arrester wires out of their mountings and crashed through both barriers in flames – wrecking a further two Corsairs and an Avenger in the forward deck park. The offending Corsair went over the side, killing its pilot. Two men of the flight deck party were also killed. Four others were injured. Damage control teams scrambled to restore the battered crash barriers. This they achieved by 1145.

Because of these problems Task Force 57 was able to launch only three Avenger strikes. These attacked the runways of Hirara.

No sooner had Victorious once again announced herself ready to accept returning aircraft than one bounced on the deck were the two destroyed arrester wires should have been and demolished one of the two patched-up crash barriers. The last remaining barrier was wrecked again later in the afternoon in another deck-landing accident.

Victorious was out of action. Some 20 of her aircraft were still airborne and had to find space among the remaining three carriers to land and stay the night. Late that evening, Victorious’ exhausted repair crews had patched up another two crash barriers and some aircraft were able to return before dusk.

At 1915, the BPF set course for rendezvous point “Cootie”.

May 18

The Logistics Support Group rendezvous in waters far from the Japanese threat was proceeding normally until all eyes in the fleet turned towards HMS Formidable.

Smoke and flames were seen billowing from the carrier's fore and aft lifts. Her hangar was ablaze: Much of her airgroup would be destroyed by an incident involving the accidental firing of a Corsairs’ guns.

The fire was contained by damage control parties within 15 minutes, but Formidable's salt-water hangar sprays were needed to douse the flames and cool the hangar. Nevertheless, the fire was prevented from doing critical damage to the ship itself - even though many of her surviving aircraft were drenched.

The accident was blamed on fatigue.

Admiral Rawlings took stock of the situation.

Formidable had lost most of her aircraft and her partially burnt-out-hangar was only lit by emergency sysems. HMS Chaser was not carrying enough reserve aircraft to restore Formidable’s air wing to full strength.

HMS Victorious was also in a precarious state: Her patched-up flight deck equipment could not take much further beating.

Finally, HMS Indomitable had been slowed by a defective shaft

The temptation was for an early return to Leyte.

The proud Admiral rejected this.

Admiral Rawlings: London Gazette

At 1104 HMS Formidable was observed to be on fire. This proved to have been caused by a Corsair in the hangar accidentally firing its guns into an Avenger; the latter exploded. Fighting this serious fire was made difficult by the fact that the fire curtains were out of action due to the earlier enemy suicide attacks.

Only extensive use of the salt-water sprays succeeded in dousing the fire, but the cost was high. Exploding ammunition and fire – along with the salt water – would leave seven Avengers and 21 Corsairs in conditions varying from complete loss to ‘flyable duds’.

By the evening the commanding officer reported that he considered his ship capable of operating with jury lighting in the hangar to replace the normal circuits that had been destroyed in the fire. Arrangements were, therefore, made to replace her damaged aircraft as far as possible, and for the ship to continue operations, at any rate for the next strike period.”

Task Force 57 would meet its commitments against Sakishima Gunto. This made the availability of Formidable’s and Victorious' flight decks a necessity.

Nevertheless, Rawlings accepted the inevitable: His hard-pressed and hard-fought ships and aircrews were fraying at the edges. He would need to set course for Australia soon for extensive refit and repairs.

Rawlings resolved to do this on May 25 if necessary, or May 29 if he could get sufficient replacement aircraft for another cycle of strikes.

But things were to only get worse that day: Light winds caused HMS Ruler lost six of her 18 Hellcats to crashes on take-off and landing. One Avenger was also lost. What was to be a training exercise for rookie replacement pilots had resulted in disaster, with three pilots and one rating killed.

Ironically, the weather was to deteriorate that evening – again limiting air operations. This time the transfer of dud and replacement aircraft between HMS Chaser and Formidable had to be suspended.

May 20

As the exhausted fleet took up position once again south of Sakishima Gunto, foul weather set in with a solid layer of low cloud producing either heavy rain or fog.

HMS Victorious had operational aircraft, but her deck equipment was suspect.

HMS Formidable had a fully operational flight deck, but few aircraft.

Between the two of them, they added the equivalent of a single fully operational armoured carrier to fight alongside HMS Indomitable and Indefatigable.

With no air operations possible, the fleet maintained its position waiting for the weather to lift.

Shortly after dawn the “KK” anti-kamikaze destroyers moved to take up position behind the carriers. But there was a heavy fog, and a particularly thick patch enveloped HMS Indomitable.

HMS Quilliam refuels at sea.

HMS Quilliam was unable to avoid striking the big carrier.

The destroyer’s bows had collapsed, but the carrier had suffered only minor damage. HMAS Norman attempted to tow Quilliam out of the combat zone but found the task difficult. At 1300 The cruiser HMS Black Prince had to be dispatched to take HMS Quilliam under tow after Norman and tugboat found it impossible to keep the destroyer on course.

WITNESS ACCOUNT:

Captain Richard Onslow

aboard HMS Quilliam“There, dead ahead, loomed a dark cliff, close but indistinct, through what I now realised was dense fog. ‘Full astern together! Hard a port!’ There was the clang of reply gongs and we sensed the revolutions building up. And then we hit. None of us on the bridge that day will ever forget what our eyes told us was happening. For we saw our stem cleave straight into Indomitable’s side and bury itself back to the muzzle of “A” gun. We felt so stunned by this apparition, for apparition thank God it was, that we hardly noticed the scream of tearing plates that accompanied it; and it was not until much later that I felt the pain of two broken ribs. Then suddenly all was quiet. We lay dead in the water in a lifeless blanket of fog – alone as the Ancient Mariner, no sound, no sight, no feeling , for feeling was numbed. I stopped the engines. I thought of Indomitable: ‘She won’t sink? She cant sink, can she? But I must have almost cut her in half. And where are my bows? I can’t have left them in her.’ So ran my thoughts. And then light dawned as I saw that the forecastle deck, where it ended, was curving downwards. We had hit her in the armour and the flare of her side had deflected our stem downwards and to port: and the rest of the wreckage had followed it out of sight.

“When the fog lifted we were alone in the wide Pacific as the sun rose on a glassy sea. I could hardly believe my ears when I heard on the TBS a message from Indomitable reporting no damage. I learnt later that the Paymaster Commanders’s looking-glass was cracked, and that he was considerably annoyed.”

At 0745 the weather lifted a little. Four bomber strikes were organised. One aircraft crashed into the sea after taking off from HMS Formidable.

The islands were themselves shrouded by thick fog but a lucky opening allowed the strike aircraft to attack Hirara town, even though their primary target had been Hirara airfield.

The Fireflies had more luck: They were able to approach very low under the cloud and rocket ground installations.

One of their escorting Corsairs from 1836 Squadron was hit by flak. The aircraft was seen to ditch, but the pilot did not make it out from his cockpit.

The weather closed again, and the second and third strikes were cancelled.

While the fourth looked doubtful, the Americans had specifically asked for an attack that evening to help reduce Japansese activity over Okinawa at dusk and by moonlight.

The strike launched at 1530 and set flight for Ishigaki. Once it the required course, speed and time had been achieved, all that was in sight was an impenetrable blanket of fog and cloud. The bombers and their escort were recalled as the weather over the task force deteriorated once again. The pilots had to be talked back to the task force by radar plots.

May 21

The morning of Admiral Rawling’s birthday revealed a day that threatened to offer a repeat of the previous day’s poor weather.

Seafires aboard HMS IMPLACABLE.

Four Hellcats were flown off at 0600 to test the conditions over the islands as the fleet sat 85 miles south-east of Miyako Jima. The Hellcats reported that the clouds were broken over the target areas, so five bomber strikes were put into motion.

The first took off at 0655 and bombed Miyako Jima’s airfields. Two further strike groups would also successfully attack Miyako, and another two Ishigaki.

Indefatigable recorded 23 Avenger, 15 Firefly and 56 Seafire sorties on this day: A record for British carriers during the ICEBERG operation.

At 1423 a bogey was detected at 30,000ft approaching the fleet from the west. CAP fighters were ordered to attempt an intercept. After 23 minutes of climbing hard, the C6N ‘Myrt’ was shot down 36 miles out from the task force at a height of 26000ft. It would be Task Force 57’s final kill.

At 1930 the fleet once again set course for ‘Cootie’.

One of HMS INDOMITABLE'S Hellcats swerves towards the deck-edge after grabbing a wire.

May 22

Admiral Rawlings, having been briefed on the plans Admiral Halsey had for his armoured carriers during the lead-up and execution the invasion of Japan, now decided he needed to have his battered force rested and repaired as soon as possible.

He would stay at Sakishima Gunto only until the 25th.

HMS Formidable, which needed extensive work to make good her damage, was to immediately set sail for Manus and Australia once she had been fully refueled. This would give the dockyards in Sydney the maximum amount of time to service her needs.

Formidable would be covered on the voyage by HMS Kempenfelt and Whirlwind, both of which were also in dire need of refit.

In their place among the fleet escort would be the veteran cruiser HMNZS Achilles, along with the destroyers Termagant and Quadrant.

During the replenishment operation, HMS Chaser again lost two Hellcat pilots. This exposed the severe lack of training these replacement pilots had received before being deployed to the combat zone.

The BPF’s misfortune would continue, however, when HMS Indomitable’s central shaft overheated. The carrier was forced to reduce her maximum speed to 22 knots.

As the sun set, HMS Formidable – with her two destroyers – separated from the task force and pointed her bows towards Sydney.

May 24

Avengers in formation above units of Task Force 57's formation.

The BPF took up station off Sakishima Gunto with only three carriers, one of which was still hindered by damaged flight deck equipment.

The temptation of a big-gun bombardment once again played on Admiral Rawling’s mind. But the prospect of exposing his three remaining carriers proved too great a risk. The battleships would stay on station, protectively clustered about the carriers.

The morning broke with a steady drizzle, low cloud and generally poor visibility.

The first Avengers were unable to get away until 1045. It was to be the first of three strikes for that day.

The 1600lb bombs cratered the runways and pulverised two parked aircraft. The Avengers and Fireflies went on to flatten several other designated targets.

No Japanese aircraft were seen in the air. The FAA lost no aircraft, neither to anti-aircraft fire nor accidents.

May 25

The last day of Operation Iceberg II dawned to much better weather.

Four Avenger and Firefly strikes were launched: The three targeting Miyako and one Ishigaki.

The Fireflies rocketed a base for suicide boats which had been identified by one of the fleet’s PR Hellcats.

Once again, no enemy aircraft were observed.

At sunset, Task Force 57 withdrew to ‘Cootie’ for the last time. Once refuelled, the carriers and the bulk of the fleet would make their way to Australian ports before the final move was made on the Japanese home islands.

Sydney, and the prospect of real rest, real relaxation, real repair and real food awaited.

HMS King George V, with Troubridge Tenacious and Termagant, however, would set sail for Guam to meet with the US Admirals.

Commander Fifth Fleet:

On completion of your two month’s operations as a Task Force of the Fifth Fleet in support of the capture of Okinawa, I wish to express to you and to the officers and men under your command, my appreciation of the fine work you have done and the splendid spirit of cooperation with which you have done it. To the American portion of the Fifth Fleet, Task Force 57 has typified the great traditions of the Royal Navy. Spruance.